Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 4, 435-444, 2025

doi: 10.53854/liim-3304-8

ORIGINL ARTICLES

Burden of neonatal pneumonia and risk factors for severe disease in low – and middle – income country

Minh Manh To1, Thi Quynh Nga Nguyen2,3, Duc Long Phi1, Van Lap Khuc1, Nhu Quynh Le1, Khanh Linh Dang1, Khanh Huyen Truong1, Trong Kiem Tran4, Thanh Tam Nguyen4, Manh Tuong Nguyen5, Phuong Thuy Nguyen Dang1, Van Thuan Hoang1, Thi Loi Dao1

1 Thai Binh University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Hung Yen, Vietnam;

2 Ha Noi University of Medicine, Hanoi, Vietnam;

3 National Pediatrics Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam;

4 Thai Binh Pediatrics Hospital, Hung Yen, Vietnam;

5 Vinmec International Hospital Times City, Vinmec Healthcare System, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam.

Article received 12 September 2025 and accepted 24 October 2025

Corresponding authors

Van Thuan Hoang

E-mail: thuanytb36c@gmail.com

Thi Loi Dao

E-mail: thiloi.dao@gmail.com

SUMMARY

Objectives: To determine morbidity, mortality, and risk factors of severe disease requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) in neonates with pneumonia in rural Vietnam.

Methods: A retrospective study was conducted and included all neonates (<28 days) admitted with pneumonia between January and December 2024. Demographics, clinical features, and laboratory results were extracted from standardized patient charts. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression were used to identify independent risk factors for IMV.

Results: Of 1,034 admissions, 612 (59.2%) met pneumonia criteria; mortality rate was 0.2%. Median age at admission was 17 days (IQR 12–23), and 61.6 % were boys. Preterm birth and low birth weight occurred in 4.6% and 6.4% of cases, respectively. Tachypnoea (96.1%), wheeze (93.0%), and signs of respiratory distress (37.7%) were predominant. Abnormal neutrophil counts were observed in 30.2%, and 5.2% had C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥10 mg/L. Independent risk factors for IMV were younger age (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.88 per day; 95% CI 0.85–0.92), neurological symptoms (aOR 24.0; 95% CI 4.07–141.67), and CRP ≥10 mg/L (aOR 3.23; 95% CI 1.22–8.52).

Conclusions: Pneumonia remains a major cause of neonatal morbidity in rural Vietnam, though mortality is low. Younger age, neurological compromise, and elevated CRP identify neonates at greatest risk for requiring IMV. Incorporating these factors into admission triage may streamline escalation of care and optimize resource allocation in neonatal units.

Keywords: neonatal pneumonia, invasive mechanical ventilation, risk factors, Vietnam.

INTRODUCTION

Neonatal pneumonia (NP), a type of lower respiratory tract infection that occurs within the first 28 days of life, is a major cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [1, 2]. It is typically classified into early-onset and late-onset forms. Early-onset NP, often acquired intrapartum and associated with Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, is significantly more frequent than late-onset NP, which is usually linked to nosocomial infections and often involves Gram-positive organisms and multidrug-resistant pathogens [3, 4]. Clinical features are often nonspecific and may overlap with neonatal sepsis, thereby making timely diagnosis difficult in settings where advanced diagnostics are not readily available [5].

Globally, neonatal infections including pneumonia, sepsis, and meningitis are among the top causes of neonatal death, contributing to nearly 1 million of the 2.3 million deaths in the first 28 days of life in 2022, with the majority occurring in the first week [6]. NP alone is estimated to be responsible for 750,000 to 1.2 million neonatal deaths annually, accounting for approximately 10% of all child mortality [4]. The burden is disproportionately high in resource-constrained regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southeast Asia, where access to skilled care, early diagnosis, and appropriate treatment remains limited [6].

Compared with older children (2 months to 5 years), neonates with pneumonia face a significantly higher risk of death due to their immature immune systems, subtle and atypical clinical presentations, and frequent comorbidities such as prematurity and low birth weight [7]. Additionally, while pneumonia in older children can often be diagnosed and managed with a combination of clinical signs and chest radiographs, these tools are frequently unavailable or unreliable for neonates in low-resource settings [4, 8].

Numerous studies have addressed the challenges of NP in LMICs [3, 4, 7, 9]. In Vietnam, despite studies have reported alarming levels of antibiotic resistance and healthcare-associated infections among hospitalized neonates, yet population-based evidence on NP in rural communities remains scarce [10-12].

Despite these valuable contributions, significant gaps in knowledge persist. Few studies have systematically examined the incidence, clinical outcomes, and contextual determinants of neonatal pneumonia in rural Southeast Asia. Moreover, current literature often focuses on urban hospital settings or tertiary Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICUs), thereby leaving the epidemiological profile of NP in rural areas poorly characterized. This is particularly concerning given that rural populations in Vietnam often face limited access to qualified health professionals, microbiological testing, and Neonatal Intensive Care (NIC) [2, 11, 13]. In these settings, pneumonia may go undiagnosed or be inadequately treated, leading to avoidable deaths.

Therefore, this study aims to estimate the morbidity and mortality attributable to neonatal pneumonia in rural areas of Vietnam. We also aim to identify the risk factors of severe disease requiring Invasive Mechanical Ventilation (IMV). The findings will contribute to a better understanding of disease burden in underserved regions and inform strategies to improve early recognition, appropriate treatment, and referral mechanisms in resource-limited settings.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design and location

This retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted among neonates hospitalized between January and December 2024 at the Thai Binh Pediatric Hospital, Thai Binh Province, Vietnam.

Thai Binh is a province located in the Red River Delta region, with an area of approximately 1,600 square kilometers and a population of around two million. The province consists of one city, which serves as the administrative, economic, and political center, and seven district-level administrative areas.

Thai Binh Pediatric Hospital is a specialized hospital responsible for providing healthcare services to children under 16 years of age across Thai Binh province and surrounding regions. It is classified as a first-class hospital and serves as the highest-level pediatric referral facility within the province. With nearly 20 departments and more than 600 inpatient beds, the hospital provides treatment for approximately 2,000 inpatients and 10,000 outpatient visits each month.

For critically ill children whose conditions exceed the hospital’s treatment capacity, referrals are made to the central pediatric facility, the Vietnam National Children’s Hospital in Hanoi, located approximately 120 kilometers away.

Studied population

As all neonates requiring inpatient treatment in Thai Binh province are admitted to Thai Binh Pediatric Hospital, we conducted a study based on the entire eligible population. All neonates under 28 days of age at the time of hospital admission who were diagnosed with pneumonia were included in the study. Pneumonia was mainly diagnosed based on clinical symptoms with rapid breathing, grunting, or chest wall retractions with fine, moist rales (crackles) and/or wheezing or rhonchi in one or both lungs in pulmonary auscultation. Chest X-ray is used for diagnosis in cases with atypical clinical manifestations [14]. A sample size calculation was not applicable to this study.

Data collection and definitions

Demographics, epidemiologic, clinical features, laboratory findings, treatment and outcomes of patients were collected by clinical doctors using a standardized questionnaire.

Preterm delivery is defined as childbirth occurring before 37 completed weeks of gestation [15]. Low birth weight is defined by the World Health Organization as a birth weight of less than 2,500 grams, regardless of gestational age [16].

An abnormal WBC count in neonates is defined as a total leukocyte count <6,000/mm³ (leukopenia) or >21,000/mm³ (leukocytosis). Abnormal neutrophil counts in neonates are based on absolute neutrophil count <1,500/mm³ (neutropenia) or >5,400/mm³ (neutrophilia) [17].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 16.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics of the study population. Continuous variables were compared between neonates who required IMV and those who did not using two-sample t-tests. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate.

To identify potential risk factors of IMV, univariate logistic regression analyses were performed for each independent variable. Candidate factors were selected based on clinical plausibility and data availability. These included neonatal age at admission (in days), sex, gestational age (term vs. preterm), low birth weight, maternal age group, maternal history of infections during pregnancy (including urinary tract infection and preeclampsia), history of gastrointestinal, cardiac, or neurological conditions, mode of delivery, elevated C-reactive protein level (CRP ≥10 mg/L), abnormal neutrophil counts, and perinatal complications such as prolonged rupture of membranes or suspected early-onset sepsis.

Missing data were assessed for all variables before analysis. Variables with more than 5% missing values were excluded from the multivariable model. Complete-case analysis was performed. Candidate predictors were first screened by univariable logistic regression, and those with a p-value less than 0.20 were considered for inclusion in the multivariable logistic regression model. A backward stepwise selection procedure was employed to construct the final model, retaining variables with a p-value less than 0.05. The strength of associations was quantified using adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

RESULTS

Characteristics of population

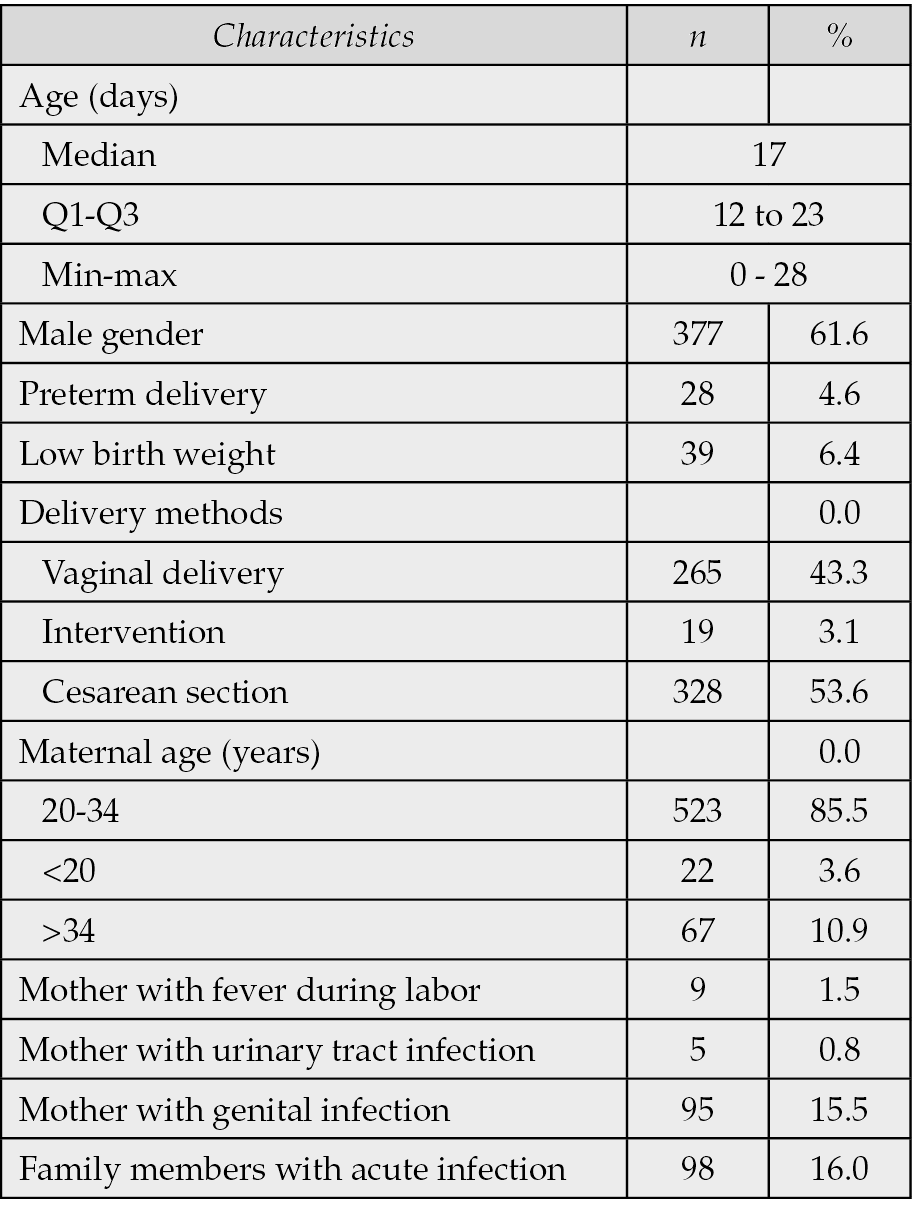

Over a one-year period, the study included 612 patients with pneumonia out of 1034 hospitalized neonates, hence the prevalence of neonatal pneumonia was 59.2%. The median age at admission was 17 days (IQR: 12–23) and 61.6% were male. Preterm delivery occurred in 4.6% of cases, and 6.4% of infants had low birth weight. Most deliveries were by cesarean section (53.6%), and the majority of mothers were aged 20–34 years (85.5%). Maternal genital infections and family members with acute infections were reported in 15.5% and 16.0% of cases, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1 - Characteristics of patients (N=612).

Clinical and laboratory findings

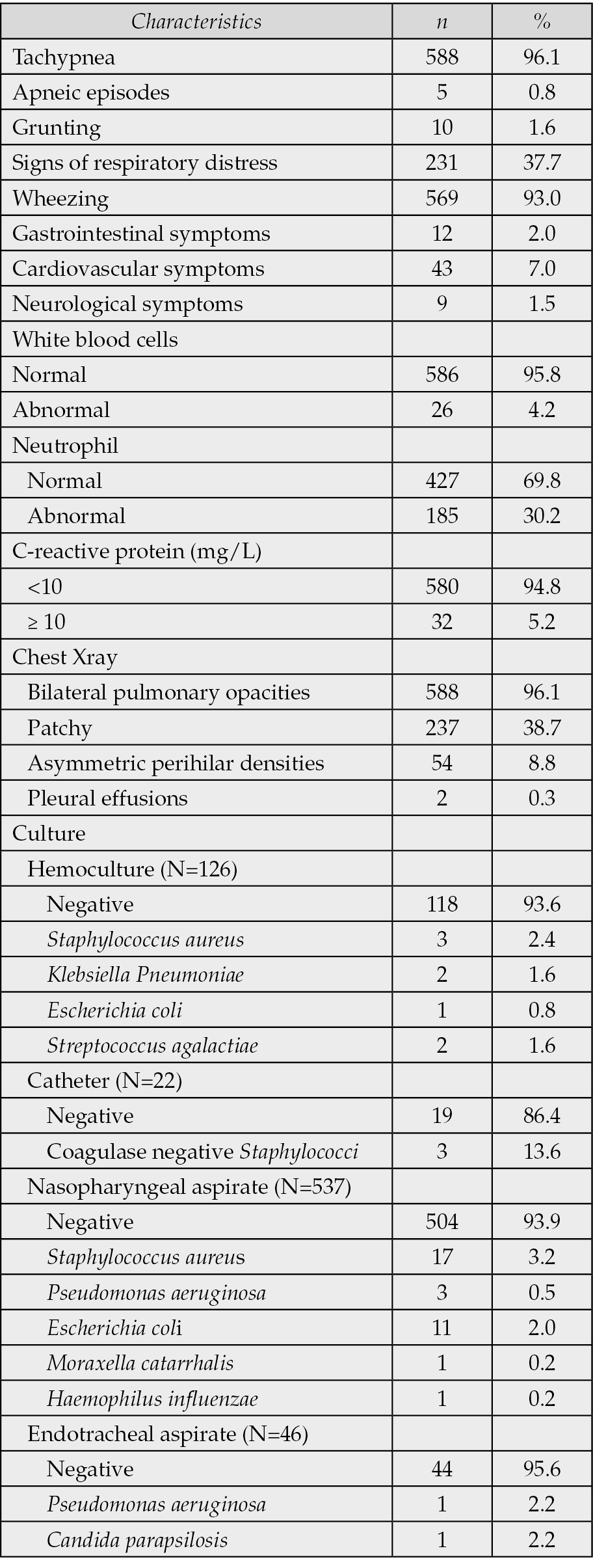

The most common presenting symptom was tachypnea (96.1%), followed by wheezing (93.0%) and signs of respiratory distress (37.7%). Laboratory findings revealed that 30.2% of patients had abnormal neutrophil counts, while 5.2% had elevated CRP levels (≥10 mg/L) (Table 2).

Table 2 - Clinical and laboratory findings (N=612).

Microbiological cultures were performed on samples from hemoculture (N=126), catheter (N=22), nasopharyngeal aspirate (N=537), and endotracheal aspirate (N=46). Among the hemocultures, 118 samples (93.6%) were negative. The most commonly identified organisms were Staphylococcus aureus (2.4%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (1.6%), Streptococcus agalactiae (1.6%), and Escherichia coli (0.8%). Of the catheter cultures, 19 samples (86.4%) showed no growth. Coagulase-negative Staphylococci were isolated in 3 cases (13.6%). Regarding nasopharyngeal aspirates, 504 samples (93.9%) were culture negative. Positive cultures included Staphylococcus aureus in 17 cases (3.2%), Escherichia coli in 11 cases (2.0%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 3 cases (0.5%), Moraxella catarrhalis in 1 case (0.2%), and Haemophilus influenzae in 1 case (0.2%). Among the endotracheal aspirates, 44 samples (95.6%) were negative. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida parapsilosis were each identified in 1 sample (2.2%) (Table 2).

Treatment and outcomes

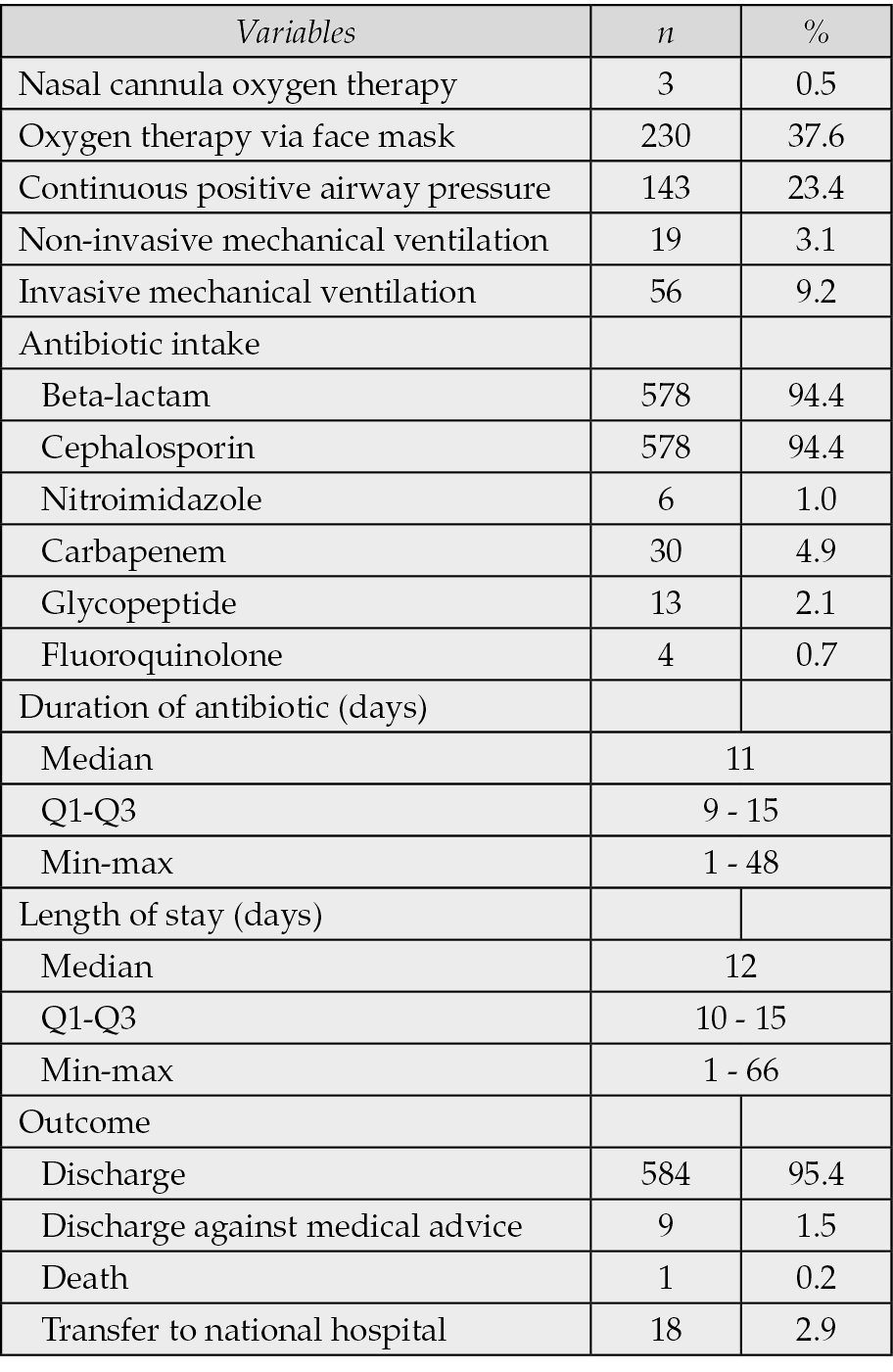

Regarding treatment modalities, 9.2% of patients required invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), and 3.1% received non-invasive ventilation. Antibiotics were administered in all patients, with 94.4% of patients receiving beta-lactams and cephalosporins as empirical therapy. The median duration of antibiotic therapy was 11 days (IQR: 9–15), and the median hospital stay was 12 days (IQR: 10–15). The majority of patients were discharged (95.4%), with only one death (0.2%) recorded (Table 3).

Table 3 - Treatment and outcomes of patients (N=612).

Risk factors of invasive mechanical ventilation

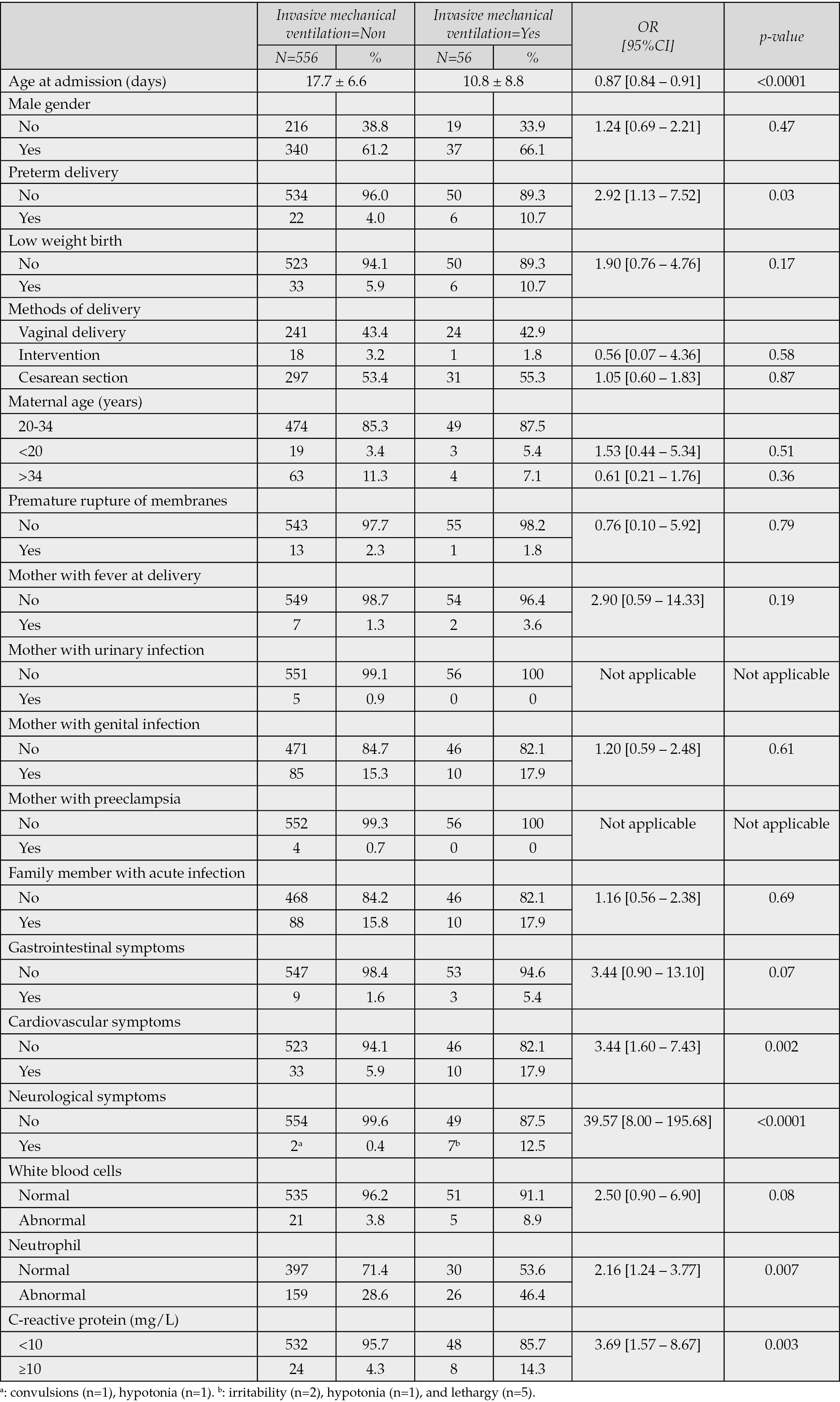

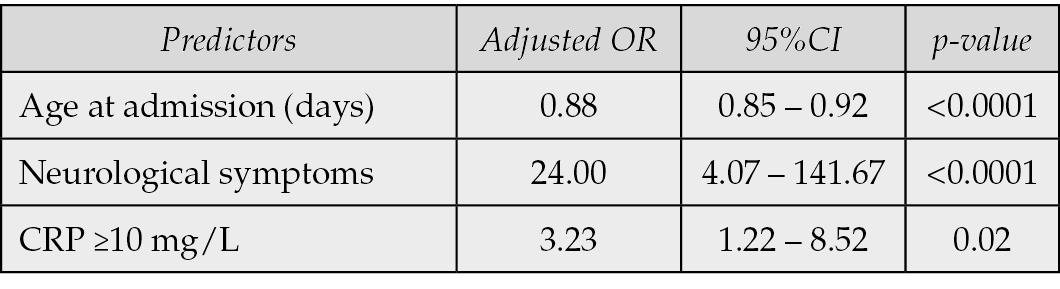

In the univariable analysis, younger age at admission (OR: 0.87; 95% CI: 0.84–0.91; p<0.0001), preterm delivery (OR: 2.92; 95% CI: 1.13–7.52; p=0.03), abnormal neutrophil count (OR: 2.16; 95% CI: 1.24–3.77; p=0.007), CRP ≥10 mg/L (OR: 3.69; 95% CI: 1.57–8.67; p=0.003), cardiovascular symptoms (OR: 3.44; 95% CI: 1.60–7.43; p=0.002), and neurological symptoms (OR: 39.57; 95% CI: 8.00–195.68; p<0.0001) were significantly associated with increased odds of requiring IMV (Table 4). In the multivariable logistic regression model, three variables remained independently associated with IMV: age at admission (aOR: 0.88; 95% CI: 0.85–0.92; p<0.0001), presence of neurological symptoms (aOR: 24.00; 95% CI: 4.07–141.67; p<0.0001), and CRP ≥10 mg/L (aOR: 3.23; 95% CI: 1.22–8.52; p=0.02) (Table 5).

Table 4 - Risk factors of IMV (univariable analysis) (N=612).

Table 5 - Risk factors of IMV (multivariable analysis) (N=612).

DISCUSSION

In our study, neonatal pneumonia accounted for 59.2% of all causes of hospitalization among neonates. Even though the mortality rate was low, this condition underscores its significant burden in the early postnatal period. The median age at admission was 17 days, suggesting that infections predominantly occurred in the late neonatal period. This finding is consistent with prior studies from low – and middle-income countries (LMICs), where the risk of infection remains high beyond the immediate perinatal window due to a combination of factors such as limited access to perinatal care, delayed diagnosis, suboptimal hygiene practices, and a high prevalence of community-acquired and healthcare-associated infections [18, 19]. These data together indicate that late-onset neonatal pneumonia remains predominant causes of critical illness and hospitalization in neonates across diverse LMIC settings.

The high prevalence of pneumonia in the late neonatal period, typically occurring after 7 days of age, may reflect increased exposure to environmental pathogens, delayed health-seeking behavior, and limited access to preventive interventions such as maternal vaccination or neonatal prophylaxis including COVID-19, pertussis, influenza, and respiratory syncytial virus. [7, 20-22]. These factors are recognized as contributors to late-onset neonatal infections. In LMIC, structural challenges exacerbate these risks because of inadequate equipment and limited resources for effective infection prevention and control. This reinforces our findings and underscore the urgent need for comprehensive infection prevention strategies. In addition to community-focused measures such as enhanced maternal immunization and education hospital-based improvements are critical. Ensuring reliable infrastructure, enforcing strict hygiene protocols, and implementing ventilator care bundles are proven and essential interventions for reducing late-onset neonatal pneumonia in LMIC contexts.

The clinical outcomes in our cohort were notably favorable, with a discharge rate of 95.4% and an exceptionally low mortality rate of 0.2%. This survival rate is significantly higher than what has been reported in comparable LMIC settings. In a study from central Vietnam, the case fatality rate among hospitalized neonates was 8.6% overall and alarmingly higher (59%) among very low birthweight infants (<1,500 g) [23]. A study conducted among Vietnamese neonates with Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia showed the mortality rate of 13% [11]. Another study evaluating the cause-specific morbidity and mortality, and referral patterns of all neonates admitted to a tertiary referral hospital in the northern provinces of Vietnam highlighted a case fatality ratio of 14%. Infection, cardiovascular and respiratory disorders were the most frequent cause of mortality [2].

Several factors likely contributed to these favorable outcomes. Early detection with prompt identification and treatment of pneumonia are critical; delayed diagnosis is a known risk factor for mortality in LMIC neonatal populations [20]. Access to respiratory support including availability of IMV may have prevented fatal respiratory decompensation. Other studies have demonstrated a strong link between inadequate ventilatory support and poor outcomes [24].

In our study, nearly all neonates received beta-lactam and cephalosporin antibiotics, and 95.4 % were successfully discharged, suggesting that most infections responded to standard empirical therapy targeting extracellular bacterial pathogens. This favorable clinical response indicates that intracellular organisms such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae or Chlamydia trachomatis, which are not covered by beta-lactams, were likely rare or clinically insignificant in our cohort. Although atypical pathogens are recognized causes of pneumonia in older infants and children, their role in neonatal pneumonia is considerably less frequent. Previous studies have shown that M. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis infections typically occur after the first month of life and are uncommon in early neonatal periods, likely due to limited exposure opportunities and passive maternal immunity [25-28].

Approximately 9.2% of patients in our cohort required invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), with an additional 3.1% managed with non-invasive modalities thereby illustrating a substantial demand for advanced respiratory support. The inverse relationship between admission age and IMV need likely highlights the underdeveloped respiratory and immune systems of younger neonates. Similar patterns were demonstrated in studies of premature infants, where lower gestational age and birth weight were major risk factors of requiring ventilatory support [7, 20].

The strong association between central nervous system involvement and IMV underscores the severity of systemic illness. Prior studies in neonatal sepsis and pneumonia have similarly identified seizures and depressed consciousness as risk factors of respiratory failure requiring ventilation [29, 30]. For instance, severe respiratory distress accompanied by altered mental status was a key risk factor for intubation in neonatal sepsis cohorts. The wide confidence interval suggests a high degree of uncertainty in the magnitude of the association. This imprecision is likely attributable to the small number of neonates with neurological disorders in the sample (only 9 cases, of which 7 required IMV), which may have resulted in unstable estimates due to sparse data. Despite the wide range, the lower bound of the confidence interval remained significantly above 1.0, reinforcing the conclusion that neurological disorders were strongly associated with increased risk for IMV.

CRP, a marker of systemic inflammation, has consistently been linked with severe neonatal infections [31]. A previous study on neonatal ventilator-associated pneumonia showed that CRP as one of inflammatory markers was significantly higher in infants who developed VAP after 72 hours of ventilation [32]. Additionally, in preterm infants, increased CRP independently correlated with higher rates of mechanical ventilation [33]. These findings align with our results, reinforcing CRP’s prognostic value in predicting respiratory compromise.

The universal use of antibiotics observed in this study highlights the clinical challenge of distinguishing neonatal pneumonia from sepsis and other respiratory conditions in low-resource settings. While empirical broad-spectrum therapy is often justified due to high mortality risk and limited diagnostic capacity, such widespread use raises important antibiotic stewardship concerns. Overuse of beta-lactams and cephalosporins may contribute to the growing burden of antimicrobial resistance in neonatal pathogens, which has been increasingly reported in Vietnam and other LMICs [34, 35]. Strengthening stewardship interventions such as guideline-based empirical therapy, early de-escalation once bacterial infection is excluded, and enhanced diagnostic capacity including CRP or procalcitonin testing could optimize antibiotic use without compromising neonatal outcomes. Integration of these principles into neonatal pneumonia management may reduce antimicrobial resistance risk while maintaining the high survival rates observed in this cohort.

This study has several limitations. It was conducted at a single tertiary hospital, which may limit the generalizability of findings to other healthcare settings, particularly primary care or rural hospitals. The diagnosis of pneumonia was based on clinical and radiological criteria without microbiological confirmation in all cases, and virological testing was not available, which may have led to misclassification between bacterial and viral etiologies. In addition, the absence of data on long-term outcomes, such as neurodevelopmental status or readmission rates, restricts our understanding of the broader impact of severe pneumonia and respiratory failure in neonates. Moreover, data on maternal vaccination status (e.g., influenza, pertussis, or COVID-19) were unavailable, limiting our ability to evaluate its potential protective effects on neonatal pneumonia. In addition, although the multivariable model identified important risk factors of IMV, the relatively small number of events (n=56) limits the statistical power and may result in overfitting. Lastly, breastfeeding is a widely recognized protective factor against pneumonia and other infectious diseases in the neonatal period, especially in low- and middle-income countries, as emphasized by UNICEF and WHO [36, 37]. However, in our study, data on feeding practices were not available due to the retrospective nature of the study. Furthermore, our cohort included only infants with a median age of 17 days (IQR 12-23), most of whom were likely still in the early postnatal period and were predominantly breastfed. Therefore, it was not possible to assess the independent association between not being breastfed and the need for invasive mechanical ventilation. However, based on previous evidence, we advocate adequate maternal and newborn care, including the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding, to reduce the burden of serious neonatal infections [38-40].

CONCLUSIONS

NP remains a major cause of hospitalization, with a substantial proportion of infants requiring respiratory support. The need for IMV was independently associated with younger age at admission, presence of neurological symptoms, and elevated CRP levels. Despite the high burden of disease, the outcomes were favorable, with low mortality and high discharge rates. These findings highlight the importance of early risk identification and could inform triage and management protocols in neonatal units. Future studies are needed to validate the predictive model in broader populations and to explore interventions that optimize antibiotic use and reduce the need for invasive ventilation.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests

Funding

No funding.

Ethic statement

The protocol was approved by the Thai Binh University of Medicine and Pharmacy (March 04, 2025; reference No. 492). The study was performed according to the good clinical practices recommended by the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. This was a retrospective study,thus informed consent was waived.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [TLD], upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: MMT, TQNN, MTN, VTH, TLD. Data curation: MMT, DLP, VLK, NQL, KLD, DCN, TKT, TTN, KHT, PTND, VTH, TLD. Formal analysis: MMT, TQNN, MTN, VTH, TLD. Investigation: MMT, TQNN, DLP, VLK, NQL, KLD, DCN, TKT, TTN, MTN, KHT, PTND, VTH, TLD. Methodology: MMT, TQNN, MTN, VTH, TLD. Software: TLD, VTH. Validation: MMT, TQNN, DLP, VLK, NQL, KLD, DCN, TKT, TTN, MTN, KHT, PTND, VTH, TLD. Visualization: MMT, TQNN, VTH, TLD. Writing - original draft: MMT, VTH, TLD. Writing - review & editing: MMT, TQNN, DLP, VLK, NQL, KLD, DCN, TKT, TTN, MTN, KHT, PTND, VTH, TLD.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our colleagues at Thai Binh Pediatric Hospital for their help in data collection

REFERENCES

[1] Hooven TA, Polin RA. Pneumonia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017; 22: 206-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2017.03.002.

[2] Miles M, Dung KTK, Ha LT, et al. The cause-specific morbidity and mortality, and referral patterns of all neonates admitted to a tertiary referral hospital in the northern provinces of Vietnam over a one -year period. PLoS One. 2017; 12: e0173407. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173407.

[3] Duke T. Neonatal pneumonia in developing countries. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005; 90(3): F211-219. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.048108.

[4] Green RJ, Kolberg JM. Neonatal pneumonia in sub-Saharan Africa. Pneumonia. 2016; 8: 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41479-016-0003-0.

[5] Garvey M. Neonatal Infectious Disease: A Major Contributor to Infant Mortality Requiring Advances in Point-of-Care Diagnosis. Antibiotics. 2024; 13: 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13090877.

[6] WHO. Newborn mortality. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborn-mortality [accessed May 10, 2025].

[7] Kumar CS, Subramanian S, Murki S, et al. Predictors of Mortality in Neonatal Pneumonia: An INCLEN Childhood Pneumonia Study. Indian Pediatr. 2021; 58: 1040-1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-021-2370-8.

[8] Kjærgaard J, Anastasaki M, Stubbe Østergaard M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute respiratory illness in children under five in primary care in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: A descriptive FRESH AIR study. PLoS One. 2019; 14: e0221389. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221389.

[9] Karki BK, Kittel G. Neonatal mortality and child health in a remote rural area in Nepal: a mixed methods study. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2019; 3: e000519. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2019-000519.

[10] Berglund B, Hoang NTB, Lundberg L, et al. Clonal spread of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae among patients at admission and discharge at a Vietnamese neonatal intensive care unit. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021; 10: 162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-021-01033-3.

[11] Nguyen TQN, Le DQ, Hoang TMH, Tran DX. Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia in neonates: clinical patterns, laboratory findings and outcomes. Pediatr Neonatol 2025; 66(4): 390-395.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedneo.2025.03.002.

[12] Peters L, Olson L, Khu DTK, et al. Multiple antibiotic resistance as a risk factor for mortality and prolonged hospital stay: A cohort study among neonatal intensive care patients with hospital-acquired infections caused by gram-negative bacteria in Vietnam. PLOS ONE. 2019; 14: e0215666. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215666.

[13] Gallagher K, Partridge C, Tran HT, Lubran S, Macrae D. Nursing & parental perceptions of neonatal care in Central Vietnam: a longitudinal qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2017; 17: 161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-017-0909-6.

[14] MSD Manual Professional Edition. Neonatal Pneumonia - Pediatrics. MSD Manual Professional Edition. Available at: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/infections-in-neonates/neonatal-pneumonia [accessed Jun 20, 2025].

[15] WHO. Preterm birth. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth [accessed 22 Jun 2025].

[16] WHO. Low birth weight. Available at: https://www.who.int/data/nutrition/nlis/info/low-birth-weight [accessed 22 Jun 2025].

[17] Virgo P. Children’s Reference Ranges for FBC. North Bristol NHS Trust. Available at: https://www.nbt.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/Childrens%20FBC%20Reference%20Ranges.pdf [accessed 22 Jun 2025].

[18] Okomo U, Akpalu ENK, Le Doare K, et al. Aetiology of invasive bacterial infection and antimicrobial resistance in neonates in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis in line with the STROBE-NI reporting guidelines. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019; 19: 1219-1234. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30414-1.

[19] Zaidi AKM, Awasthi S, deSilva HJ. Burden of infectious diseases in South Asia. BMJ. 2004; 328: 811-815. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7443.811.

[20] Nair NS, Lewis LE, Dhyani VS, et al. Factors Associated With Neonatal Pneumonia and its Mortality in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Indian Pediatr. 2021; 58: 1059-1066. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-021-2374-4.

[21] Ginsburg AS, Meulen AS, Klugman KP. Prevention of neonatal pneumonia and sepsis via maternal immunisation. The Lancet Global Health. 2014; 2: e679-680. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70317-1.

[22] Barros FC, Gunier RB, Rego A, et al. Maternal vaccination against COVID-19 and neonatal outcomes during Omicron: INTERCOVID-2022 study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2024; 231: 460.e1-460.e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2024.02.008.

[23] Tran HT, Doyle LW, Lee KJ, Dang NM, Graham SM. Morbidity and mortality in hospitalised neonates in central Vietnam. Acta Paediatr. 2015; 104: e200-205. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12960.

[24] Graham HR, Bakare AA, Ayede AI, et al. Oxygen systems to improve clinical care and outcomes for children and neonates: A stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial in Nigeria. PLoS Med. 2019; 16: e1002951. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002951.

[25] Le KD, To MM, Dang VN, Hoang VT. High prevalence and associated factors of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children under 5 years with atypical pneumonia. Jf Prev Med Hyg. 2025; 66: E358-E358. https://doi.org/10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2025.66.3.3574.

[26] Phi DL, To MM, Le KD, et al. Commentary: Adenovirus and Mycoplasma pneumoniae co-infection as a risk factor for severe community-acquired pneumonia in children. Front Pediatr. 2024; 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2024.1464813.

[27] Waites KB, Xiao L, Liu Y, Balish MF, Atkinson TP. Mycoplasma pneumoniae from the Respiratory Tract and Beyond. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017; 30: 747-809. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00114-16.

[28] Wang D, Yang C, Qin D, Wang J, Zhao J. Case Report: A neonatal case of severe congenital Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia with atelectasis and macrolide resistance. Front Pediatr. 2025; 13: 1561097. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2025.1561097.

[29] Nygaard U, Hartling UB, Nielsen J, et al. Hospital admissions and need for mechanical ventilation in children with respiratory syncytial virus before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2023; 7: 171-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00371-6.

[30] Trusinska D, Zin ST, Sandoval E, Homaira N, Shi T. Risk factors for poor outcomes in children hospitalized with virus-associated acute lower respiratory infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2024; 43: 467-476. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000004258.

[31] Eichberger J, Resch E, Resch B. Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis: The Role of Inflammatory Markers. Front Pediatr. 2022; 10: 840288. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.840288.

[32] Zhao X, Xu L, Yang Z, et al. Significance of sTREM-1 in early prediction of ventilator-associated pneumonia in neonates: a single-center, prospective, observational study. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2020; 20: 542. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05196-z.

[33] Yue G, Wang J, Li H, Li B, Ju R. Risk Factors of Mechanical Ventilation in Premature Infants During Hospitalization. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021; 17: 777-787. https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S318272.

[34] Laxminarayan R, Matsoso P, Pant S, et al. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. Lancet. 2016; 387: 168-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00474-2.

[35] WHO. Implementing the global action plan on antimicrobial resistance: first quadripartite biennial report. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240074668 [accessed Oct 25, 2025].

[36] WHO. Infant and young child feeding. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding [accessed Oct 25, 2025].

[37] UNIVEF. Why breastfeeding is critical for babies. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/nutrition/why-breastfeeding-best-babies [accessed Oct 25, 2025].

[38] Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016; 387: 475-490. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7.

[39] Lamberti LM, Zakarija-Grković I, Fischer Walker CL, et al. Breastfeeding for reducing the risk of pneumonia morbidity and mortality in children under two: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13: S18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S18.

[40] Abate BB, Tusa BS, Sendekie AK, et al. Non-exclusive breastfeeding is associated with pneumonia and asthma in under-five children: an umbrella review of systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Breastfeed J. 2025; 20: 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-025-00712-w.