Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 4, 422-434, 2025

doi: 10.53854/liim-3304-7

ORIGINL ARTICLES

Efficacy of Imipenem/Cilastatin/Relebactam in infections caused by Difficult-to-Treat Gram-Negative Bacteria: A Retrospective Analysis of Real-world data in Greece

Vasileios Petrakis1, Petros Rafailidis1, Maria Panopoulou2, Theocharis Konstantinidis2, Nikoleta Babaka1, Dimitrios Papazoglou1, Periklis Panagopoulos1

12nd University Department of Internal Medicine, Department of Infectious Diseases, University General Hospital Alexandroupolis, Democritus University Thrace, Greece;

2University Laboratory Department, University General Hospital Alexandroupolis, Democritus University Thrace, Greece.

Article received 10 September 2025 and accepted 29 October 2025

Corresponding author

Vasileios Petrakis

E-mail: vasilispetrakis1994@gmail.com

SUMMARY

Background: The escalating global crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), particularly among multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria (GNB), presents a significant challenge to patient care. Newer β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor (BL/BLI) combinations, such as imipenem/cilastatin/relebactam (IMI/REL), have been developed to overcome key resistance mechanisms, including those mediated by KPC and AmpC enzymes, offering new hope for treating severe infections with limited therapeutic options.

Patients and Methods: This was a retrospective, single-center, observational study of 195 adult patients with GNB bacteraemia who received IMI/REL for at least 48 hours. The patient cohort was characterized by a high comorbidity burden (median Charlson Comorbidity Index of 4) and significant illness severity (median APACHE II score of 14). The most common pathogens were Pseudomonas aeruginosa (63.1%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (24.6%), with a high proportion of isolates being carbapenem-non-susceptible (77.5%). The primary outcome was clinical success, and secondary outcomes included 30-day all-cause mortality and safety.

Results: The overall clinical success rate was 72.82%, and the all-cause 30-day mortality rate was 11.3%. Microbiologic failure occurred in 12.3% of patients, and infection recurrence within 30 days was seen in 8.2%. The safety profile was favourable, with adverse drug reactions reported in 4.1% of patients, leading to treatment discontinuation in only two cases (1.02%).

Conclusions: The findings of this study reinforce the value of IMI/REL as an effective and well-tolerated treatment for severe GNB infections in a complex, real-world patient population. These outcomes compare favourably with published data for other new BL/BLI agents, supporting the targeted use of IMI/REL as a crucial component of modern antibiotic stewardship.

Keywords: Imipenem/cilastatin/relebactam, IMI/REL, bacteraemia, Gram-negative bacteria, multidrug-resistant, antimicrobial resistance, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

INTRODUCTION

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a pressing global health crisis, particularly the rising prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria (GNB) [1]. The emergence of MDR and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) pathogens has rendered many conventional antibiotics ineffective, creating significant therapeutic challenges for clinicians and leading to increased rates of morbidity, mortality, and economic burden [2]. According to recent data, resistant infections cause over 1.27 million deaths annually, and unchecked AMR could result in economic damage comparable to the 2008 financial crisis [3]. This crisis is exacerbated because the evolution of resistance mechanisms has significantly outpaced new antibiotic development, creating a widening therapeutic gap that threatens the foundation of modern medical practices [4].

A critical component of this challenge is the rise of resistance to cornerstone β-lactam antibiotics, primarily driven by the production of β-lactamase enzymes that inactivate these drugs [5]. In response, the last decade has witnessed the development and approval of several innovative β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor (BL/BLI) combinations designed to circumvent these resistance mechanisms and restore therapeutic efficacy [6]. These newer agents, including ceftazidime/avibactam, meropenem/vaborbactam, ceftolozane/tazobactam, and imipenem/cilastatin/relebactam, each possess a unique microbiological profile tailored to specific resistance phenotypes, filling a critical gap in the antimicrobial armamentarium [7]. Imipenem/cilastatin/relebactam (IMI/REL) stands out as a crucial addition. It combines a potent carbapenem, a renal dehydropeptidase inhibitor, and a novel bicyclic diazabicyclooctane inhibitor that effectively restores imipenem’s activity against many Ambler Class A and Class C enzymes, such as KPC-type carbapenemases and AmpC β-lactamases [8-10]. IMI/REL is indicated for a range of serious infections, including hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (HABP/VABP), complicated urinary tract infections (cUTI), and complicated intra-abdominal infections (cIAI) [9].

While data from pivotal clinical trials and in vitro studies have demonstrated the efficacy of IMI/REL against these formidable pathogens, there remains a critical need for real-world evidence. Retrospective, observational studies are vital for providing insights into the use of new antibiotics in diverse patient populations with complex comorbidities, a context often not fully captured in controlled trials. This study aims to address this gap by retrospectively analysing the clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and outcomes of a cohort of 195 patients with bacteraemia caused by GNB treated with IMI/REL. By synthesizing our findings with the existing literature, this article seeks to provide a comprehensive analysis of the real-world utility of IMI/REL in the management of GNB bacteraemia.

METHODS

This was a retrospective, single-centre, observational study conducted at Second University Department of Internal Medicine and Department of Infectious Diseases of University General Hospital of Alexandroupolis (Greece). The study included adult patients who were hospitalized during the period from January 2023 to January 2025 and received IMI/REL for at least 48 hours for microbiologically confirmed Gram-negative bacteraemia due to difficult-to-treat (DTR) pathogens. While IMI/REL therapy may have been initiated empirically in some cases, inclusion in the final cohort was contingent upon subsequent positive blood culture confirmation of a DTR Gram-negative bacterium. Patients were excluded from the study if any of the following criteria were met: age less than 18 years, pregnancy or lactation, polymicrobial infection where a DTR Gram-negative bacterium was not considered the primary pathogen and patients for whom complete medical records or outcome data were unavailable for retrospective review. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, as this was a specific requirement of the Institutional Review Board for the retrospective analysis of patient medical records. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University General Hospital of Alexandroupolis and Democritus University of Thrace.

Data were extracted from patient medical records, encompassing demographics, clinical characteristics, microbiological findings, and details regarding the administration of IMI/REL. The source of infection, isolated pathogens and their resistance phenotypes were meticulously recorded. The primary outcome was the clinical success, defined as improvement or resolution of infection-related signs and symptoms at the end of treatment. The assessment of clinical success was determined by the documented evidence extracted from the patient’s medical records. Treating physician’s documented assessment at the end of treatment with IMI/REL therapy or at the point of patient discharge was reviewed. A statement of “clinical success”, “significant clinical improvement” or “resolution of infection” was required. Resolution or marked improvement of systemic signs of infection, specifically the normalization of fever and clearance or improvement of source-specific signs and symptoms such as clearance of purulent secretions for respiratory tract infections, or resolution of flank pain/dysuria for urinary tract infections were reported. The successful completion of the IMI/REL course without the need to switch to an alternative agent due to clinical deterioration or insufficient response prior to the end of the planned treatment course was also assessed. The secondary outcomes included the 30-day all-cause mortality, microbiologic failure (defined as the isolation of the original pathogen after 30 days of treatment), infection recurrence within 30 days, length of hospital stay, and infection-related readmission within 30 days. Infection recurrence was clinically assessed as the re-isolation of the original Gram-negative pathogen or a clinically related infection within 30 days following the end of IMI/REL therapy. Clinical Failure was defined as the lack of improvement or resolution of infection-related signs and symptoms at the end of IMI/REL treatment. This is the inverse of our primary endpoint, clinical Success. Adverse drug reactions were also monitored and reported from the medical records.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics, treatment outcomes, and adverse events. Continuous variables were presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs), and categorical variables as counts and percentages. To assess factors associated with 30-day all-cause mortality, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed. Variables with a p-value of <0.1 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model. Odds Ratios (OR) and adjusted Odds Ratios (aOR) with their respective 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) were calculated. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was conducted to estimate the probability of 30-day all-cause mortality and time-to-infection recurrence. The log-rank test was used to compare survival distributions between stratified groups (e.g., ICU vs. non-ICU patients). A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

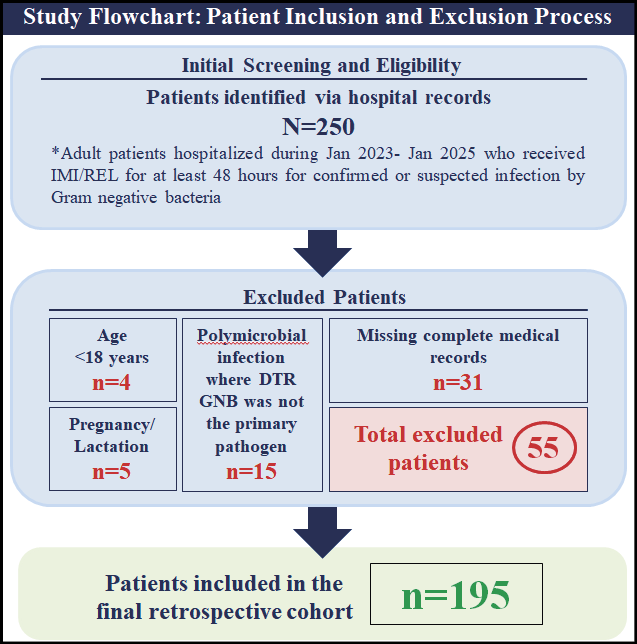

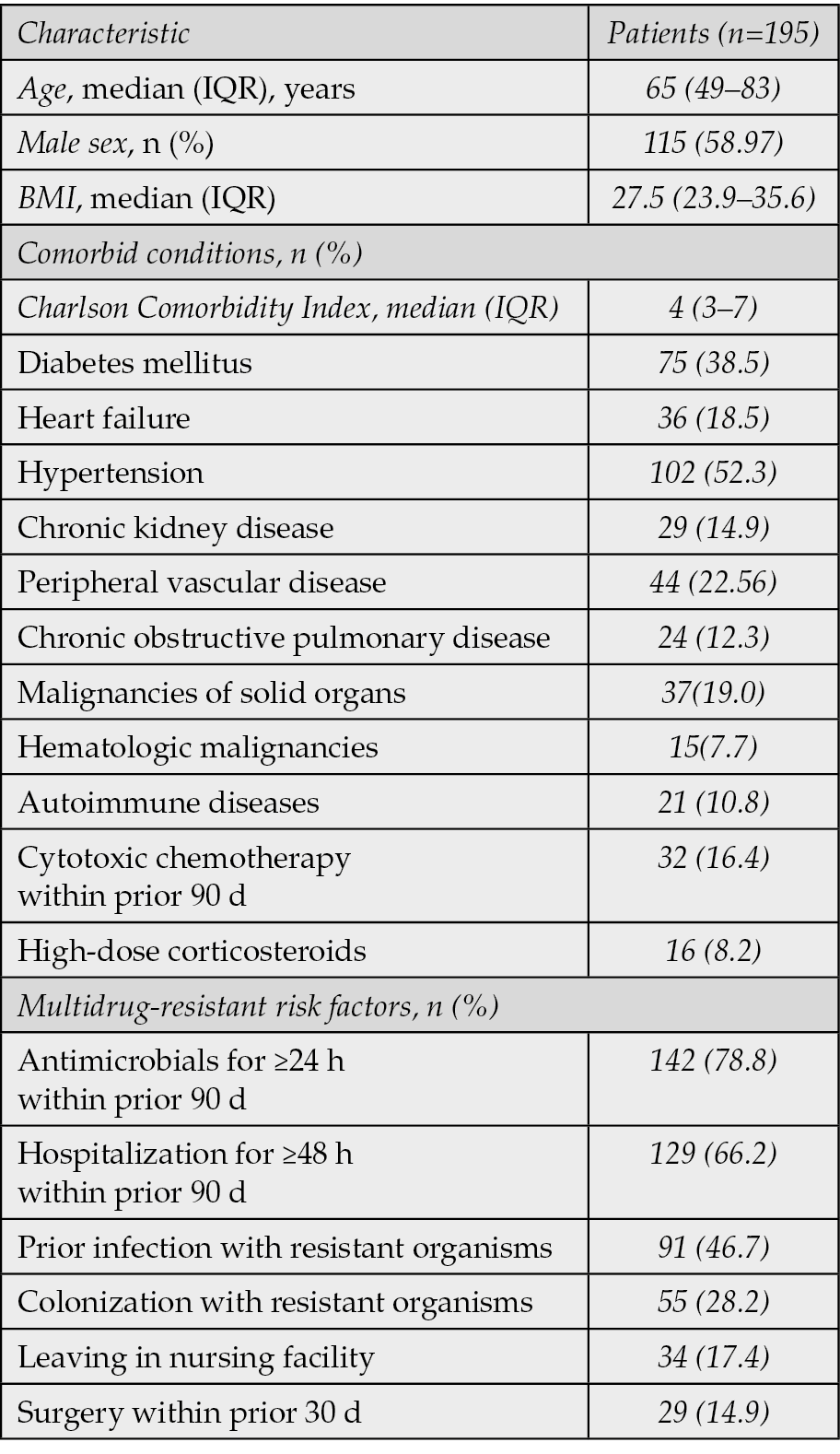

A total of 195 patients were included in the analysis. The flowchart summarizing the study design and the patient inclusion process is shown in Figure 1. The median age was 65 years (interquartile range, 49-83) and 58.97% of patients were male (Table 1). The median body mass index (BMI) was 27.5 (IQR, 23.9-35.6). The cohort had a high burden of comorbidities, with a median Charlson Comorbidity Index of 4 (IQR, 3-7). The most frequent comorbidities were hypertension (52.3%), diabetes mellitus (38.5%), and heart failure (18.5%). Consistent with the study’s focus, a substantial portion of the cohort had multidrug-resistant risk factors, including recent antibiotic exposure (78.8%) and hospitalization (66.2%). Illness severity was high, with a median APACHE II score of 14 (IQR, 9-22), and 13.3% of patients were admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at the time of index culture (Table 2).

Figure 1 - Flowchart of the study and patient inclusion process.

Table 1 - Clinical characteristics of study participants (n=195).

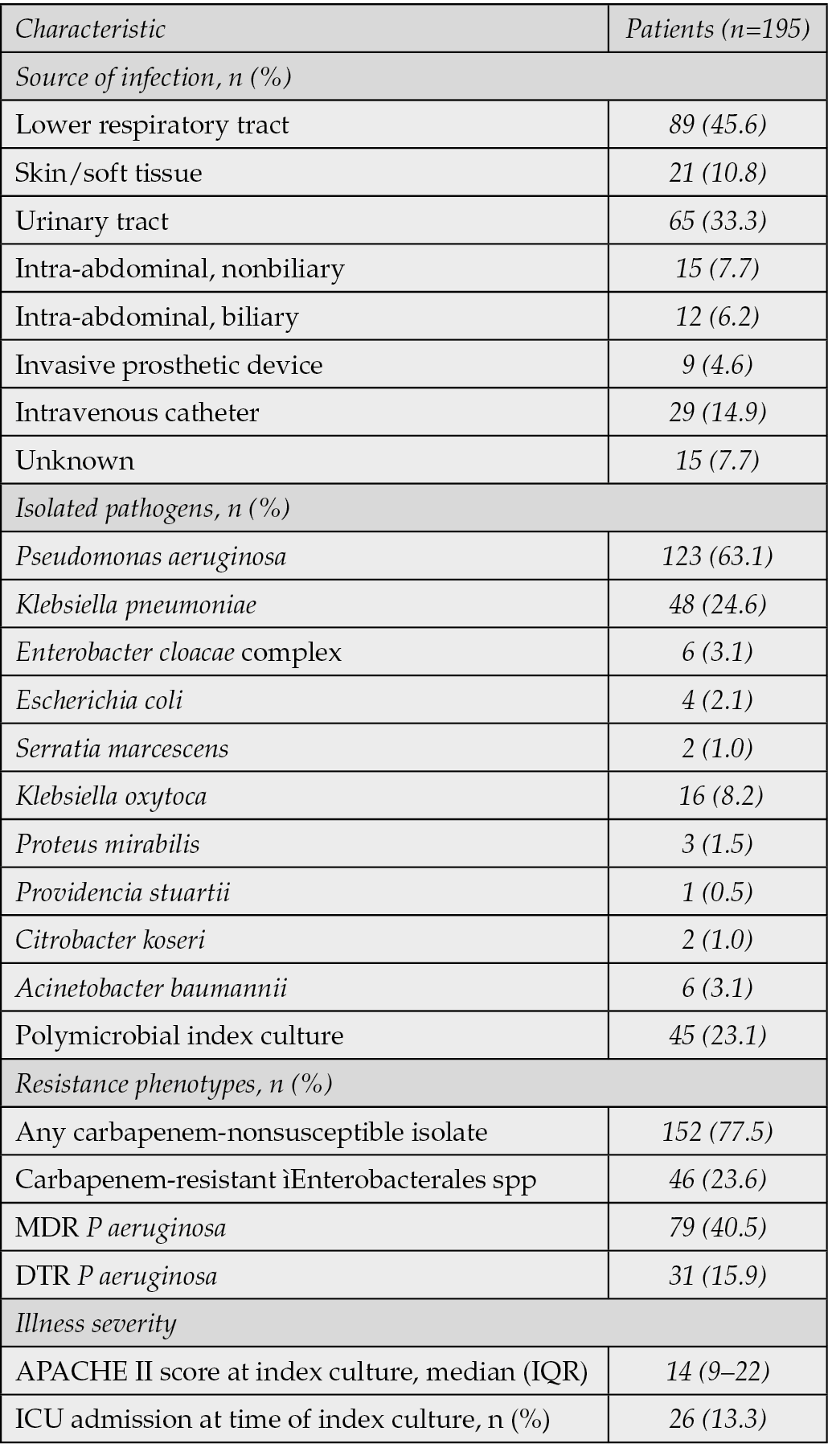

Table 2 - Source of infection, isolated pathogens and resistance phenotypes in study participants.

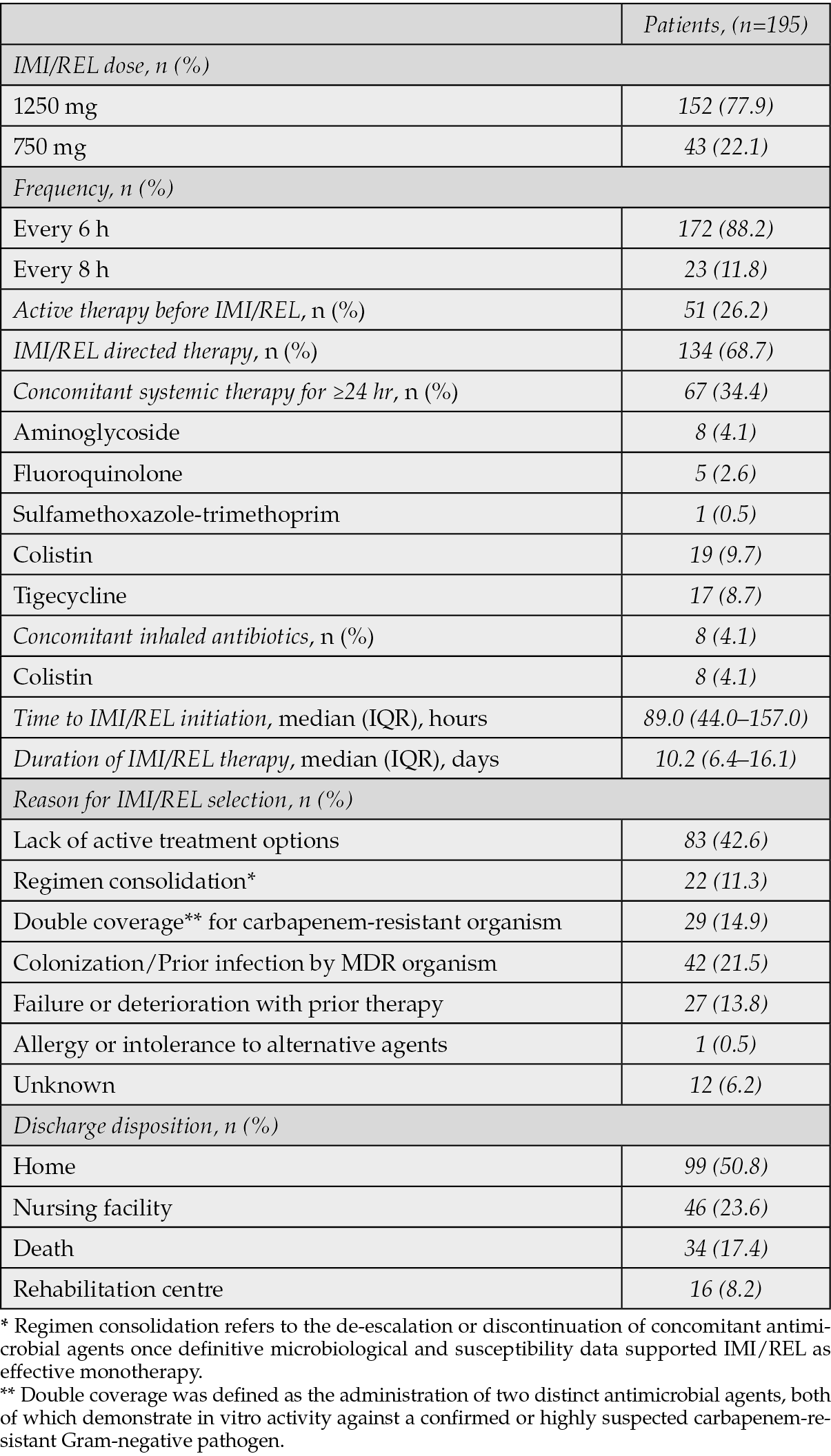

The most common source of infection was the lower respiratory tract (45.6%), followed by the urinary tract (33.3%) and intravenous catheter infections (14.9%) (Table 2). The median duration of IMI/REL therapy was 10.2 days (IQR, 6.4-16.1) (Table 3). The drug was administered primarily at a dose of 1250 mg (77.9%) every 6 hours (88.2%). Of the 195 patients included in the study, 51 (26.2%) were receiving active antimicrobial therapy immediately prior to the initiation of IMI/REL. The decision to switch to IMI/REL in these cases was driven by critical clinical and microbiological considerations. The primary reasons for this change included documented clinical deterioration or lack of adequate response to the prior antimicrobial regimen, microbiological guidance indicating in vitro non-susceptibility or suboptimal activity of the current agents against the isolated DTR Gram-negative pathogen, or clinical judgment to escalate therapy due to severe infection or specific resistance patterns for which IMI/REL was seemed a more appropriate and effective option.

Table 3 - Data associated with the administration of Imipenem/Cilastatin/Relebactam.

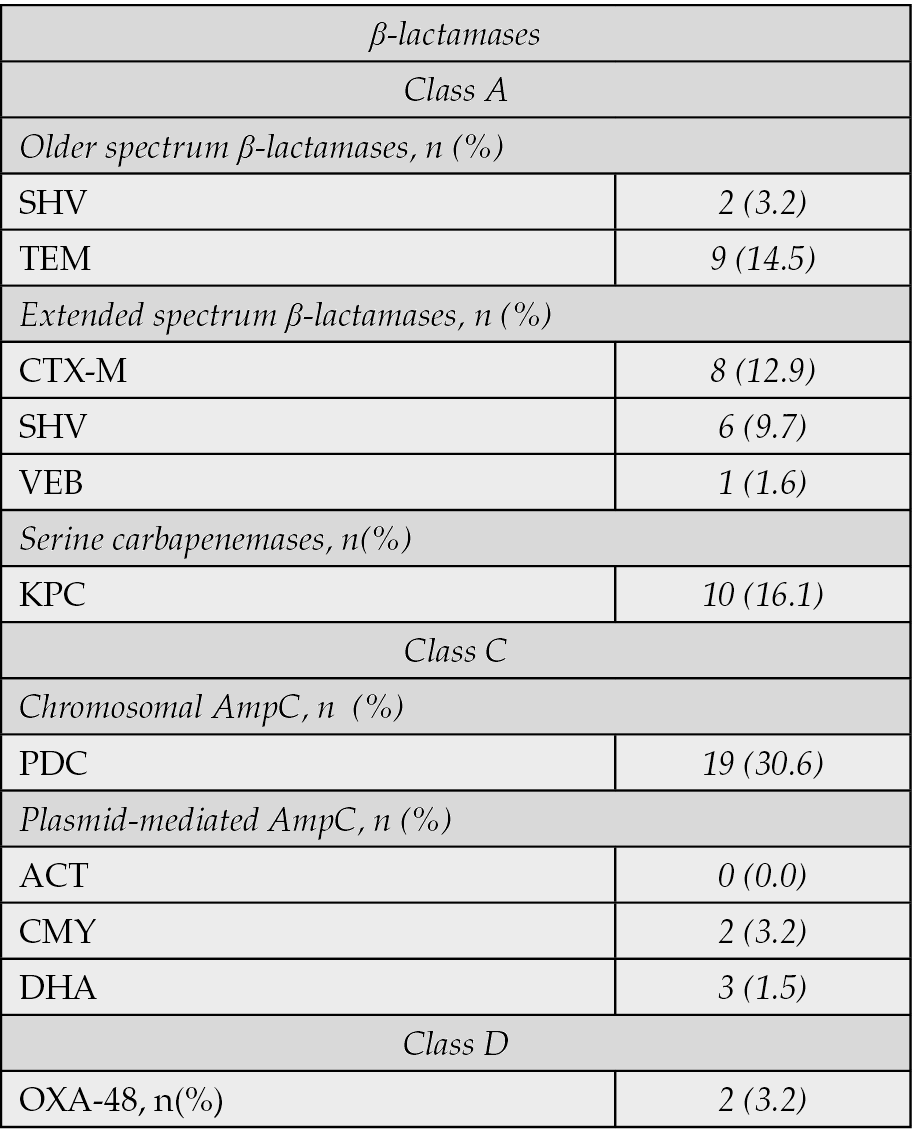

Pseudomonas aeruginosa was the most frequently isolated pathogen (63.1%), followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae (24.6%). A significant proportion of isolates were carbapenem-non-susceptible (77.5%), with 23.6% being Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales (CRE). The remaining 43 isolates (22.5%) were carbapenem-susceptible but met the definition of difficult-to-treat due to non-susceptibility to multiple other standard antimicrobial classes (e.g., extended-spectrum cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, or piperacillin-tazobactam), necessitating the use of advanced agents like IMI/REL. Among P. aeruginosa isolates, 40.5% were multidrug-resistant (MDR) and 15.9% were difficult-to-treat-resistant (DTR). The remaining 59.5% (n=73) of P. aeruginosa isolates were either non-MDR or susceptible to at least one of the major antipseudomonal classes (carbapenems, extended-spectrum cephalosporins, or piperacillin-tazobactam), but still met the overall study definition of a DTR-GNB for which IMI/REL therapy was chosen based on specific resistance to other agents or clinical context. In a subset of 62 isolates, specific β-lactamases were identified, including chromosomal AmpC (PDC, 30.6%), KPC serine carbapenemases (16.1%), and a variety of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (Table 4).

Table 4 - Classification of isolates based on type of β-lactamases (n=62).

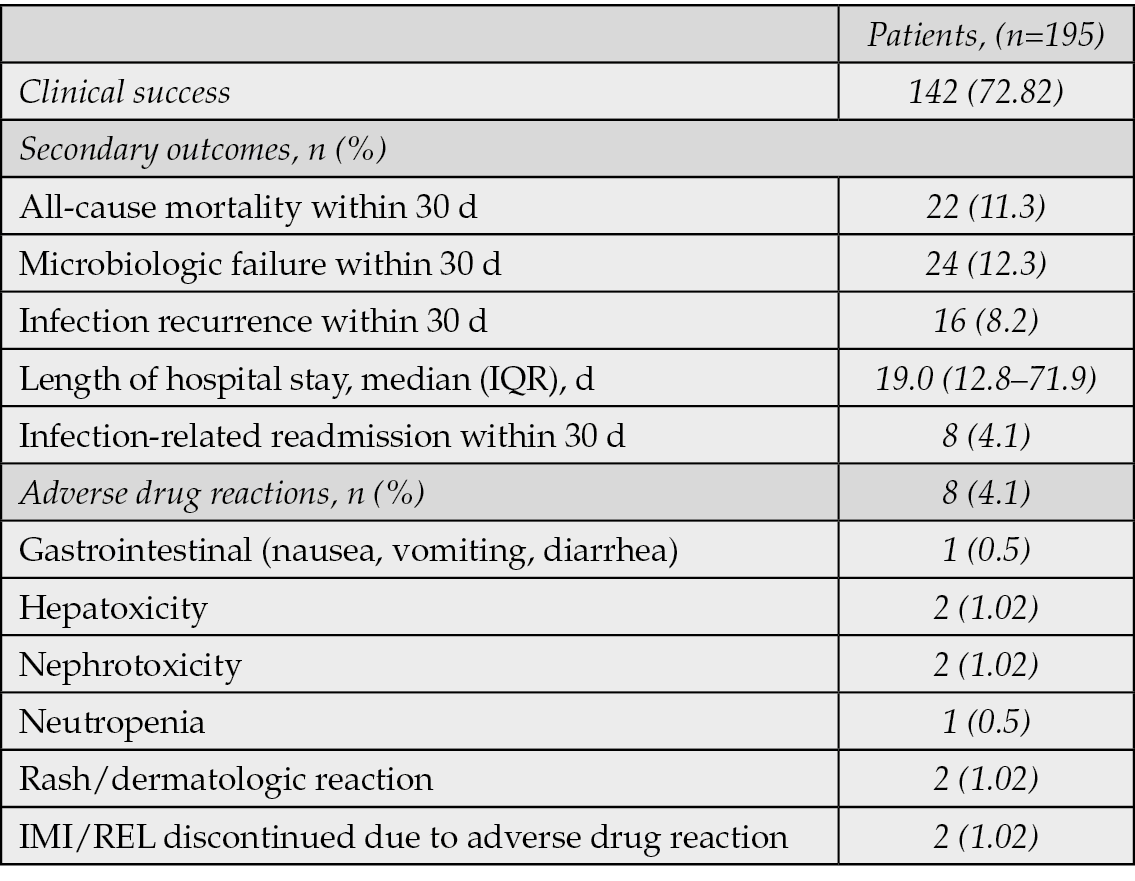

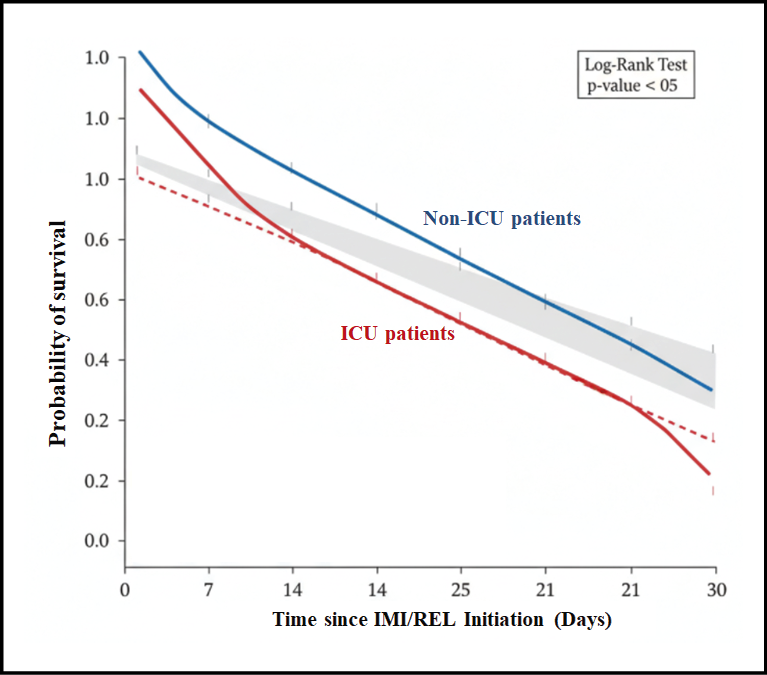

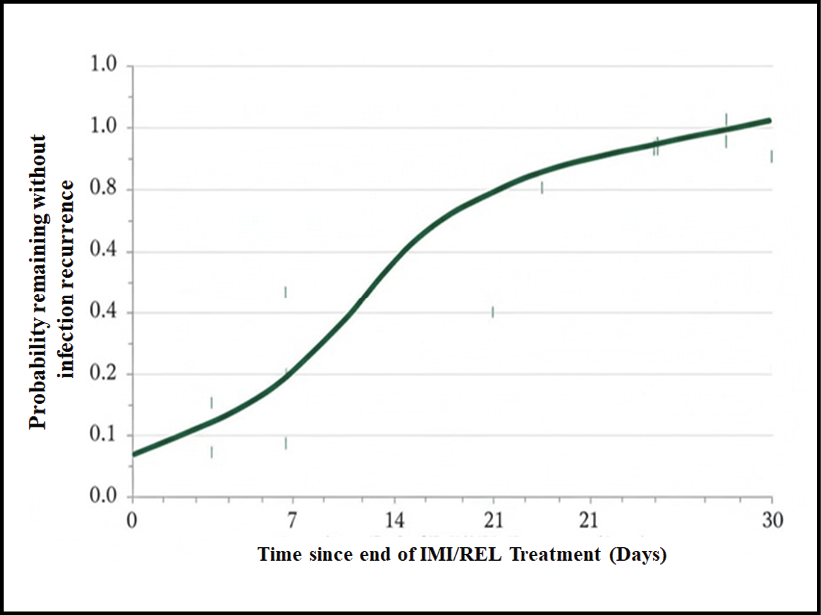

The overall clinical success rate was 72.82% (Table 5). The 30-day all-cause mortality rate was 11.3%, affecting 22 patients. Microbiologic failure occurred in 24 patients (12.3%) and infection recurrence within 30 days was seen in 16 patients (8.2%). As previously clarified, a substantial portion of our cohort, 51 patients (26.2%), were switched to IMI/REL due to either documented clinical deterioration or microbiological non-susceptibility with their prior active antimicrobial therapy representing a high-risk group. Among these 51 patients, the clinical success rate was 60.8% (n=31/51), which is notably lower than the overall clinical success rate of 72.82% for the entire cohort. The 30-day all-cause mortality rate in this subgroup was 19.6% (n=10/51). This is higher than the overall 30-day mortality rate of 11.3% for the entire cohort. Microbiological eradication in this group was achieved in 58.8% (n=30/51) of cases, lower than the overall rate of 78.5%. The overall median length of hospital stay was 19.0 days, and 4.1% of patients had infection-related readmission within 30 days. Among patients with a high comorbidity burden (n=51) the median length of hospital stay was 27.5 days (IQR: 18.0–45.0) and the risk of readmission within 30 days was measurably higher (n=9/51, 17.64%). Kaplan–Meier survival curve for 30-day mortality and for time remaining without infection recurrence are shown in Figures 2 and 3. Adverse drug reactions were reported in 4.1% of patients, with hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity each occurring in 1.0%. Only two patients (1.02%) discontinued the treatment due to an adverse drug reaction.

Table 5 - Efficacy, clinical outcome and safety in study participants after treatment with Imipenem/Cilastatin/Relebactam.

Figure 2 - Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis for 30-Day All-Cause Mortality in Patients Treated with Imipenem/Cilastatin/Relebactam (n=195)

Note: The curve plots the probability of survival from the day of IMI/REL initiation up to 30 days. The blue line represents non-ICU patients (n=169), and the red line represents ICU patients (n=26) at the time of index culture. The grey shaded areas indicate the 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3 - Kaplan-Meier Curve for Time-to-Infection Recurrence within 30 Days Post-Treatment (n=142 Clinically Successful Cases).

The curve plots the probability of remaining infection-free over 30 days following the end of IMI/REL therapy. Patients who died or were lost to follow-up within 30 days were censored.

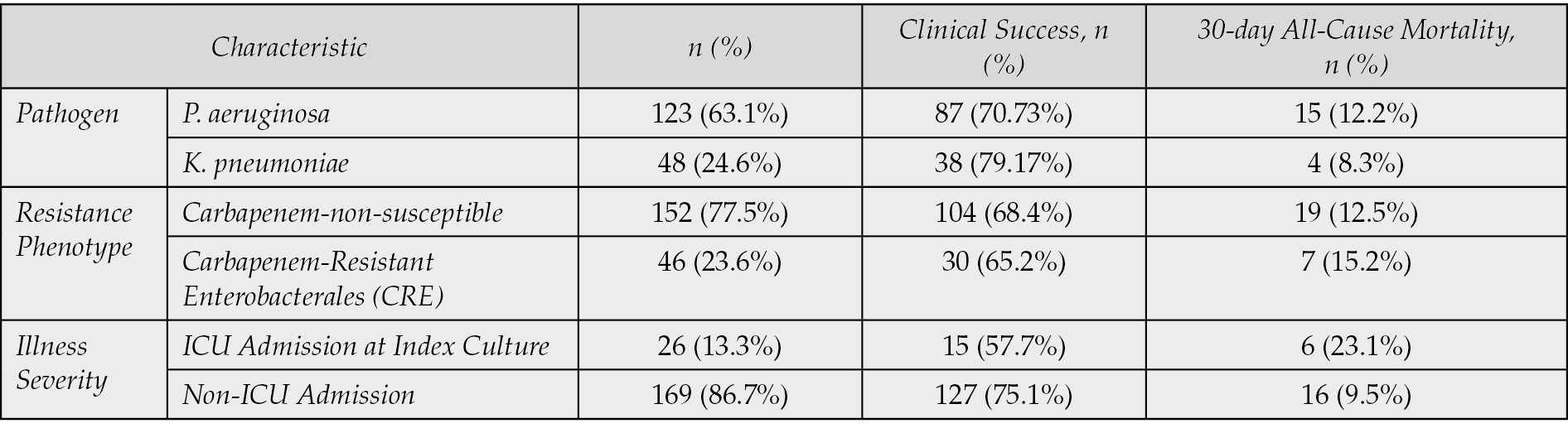

The stratified analysis revealed significant differences in IMI/REL efficacy across various subgroups of patients, as detailed in Table 6. While the overall clinical success rate was 72.82%, success was notably higher against Klebsiella pneumoniae (79.17%) compared to Pseudomonas aeruginosa (70.73%), and correspondingly, 30-day mortality was lower in the K. pneumoniae group (8.3% vs. 12.2% for P. aeruginosa). When examining resistance, IMI/REL maintained efficacy against highly resistant phenotypes, achieving a clinical success rate of 68.4% in the full cohort of carbapenem-non-susceptible isolates and 65.2% against CRE, with an associated 30-day mortality rate of 15.2% for CRE infections. Critically, illness severity proved to be the strongest predictor of outcome: patients admitted to the ICU at the time of index culture, who represented 13.3% of the cohort, had a significantly lower clinical success rate (57.7%) and a more than two-fold higher 30-day all-cause mortality rate (23.1%) compared to non-ICU patients (75.1% success and 9.5% mortality).

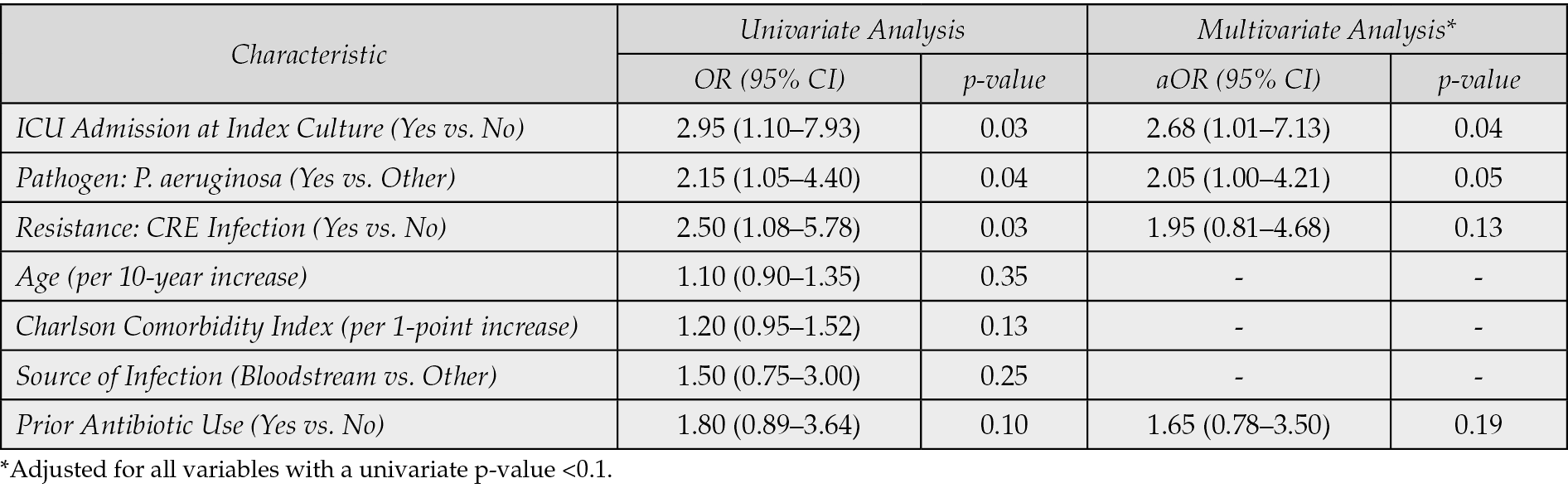

In the univariable analysis, several factors were found to be significantly associated with increased 30-day all-cause mortality (Table 7). These included ICU admission (Odds Ratio [OR]: 2.95; 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.10–7.93; p=0.03), infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (OR: 2.15; 95% CI: 1.05–4.40; p=0.04), and the presence of a CRE infection (OR: 2.50; 95% CI: 1.08–5.78; p=0.03). Factors such as age, gender, and type of infection source (e.g., bloodstream vs. respiratory) did not show a statistically significant association with mortality in the univariate analysis. Variables with a p-value less than 0.1 in the univariable analysis were considered for the multivariable model. After adjusting for confounding factors, ICU admission remained an independent predictor of 30-day all-cause mortality (Adjusted OR [aOR]: 2.68; 95% CI: 1.01–7.13; p=0.04). Similarly, infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa also maintained its independent association with increased mortality (aOR: 2.05; 95% CI: 1.00–4.21; p=0.05). The association with CRE infection, while still indicating increased risk, did not reach statistical significance in the multivariate model after adjusting for other factors (aOR: 1.95; 95% CI: 0.81–4.68; p=0.13), suggesting its effect might be partially mediated by or correlated with other severe disease parameters often found in ICU settings.

A substantial proportion of our patients, 67 (34.4%), received concomitant systemic antimicrobial therapy for ≥24 hours alongside IMI/REL. This reflects the severe and often complex clinical scenarios encountered in patients with DTR-GNB bacteraemia. In 29 cases (14.9% of the total cohort), concomitant therapy was utilized to provide broader coverage for suspected or confirmed co-infecting pathogens (e.g., Gram-positives, anaerobes, or other resistant Gram-negatives not fully covered by IMI/REL), given that 45 (23.1%) of patients had polymicrobial infections identified. In 19 cases (9.7%), concomitant therapy specifically included colistin, and in 17 cases (8.7%), it included tigecycline, often in combination with IMI/REL. This strategy aimed to provide wider coverage against highly resistant strains, particularly for CRE or extensively drug-resistant (XDR) P. aeruginosa. Beyond antimicrobials, a significant number of these critically ill patients (39% had septic shock at baseline) received other systemic therapies such as vasopressors (28.7%) and corticosteroids for septic shock (11.8%). While our study was not designed to prospectively compare outcomes of IMI/REL monotherapy versus combination therapy, our univariate logistic regression analysis for 30-day all-cause mortality, which included “Prior Antibiotic Use” as a proxy for complexity (and often indicative of a switch to IMI/REL or continued combination), did not find this factor to be an independent predictor of mortality (OR: 1.80; 95% CI: 0.89–3.64; p=0.10). Similarly, in the multivariate model, it remained non-significant (aOR: 1.65; 95% CI: 0.78–3.50; p=0.19). This suggests that, in our cohort, the use of concomitant systemic therapy, while a marker of patient complexity or severe resistance did not independently worsen patient outcomes, nor did it provide a statistically significant additional protective effect against 30-day mortality that could overcome the strong influence of factors like ICU admission or P. aeruginosa infection.

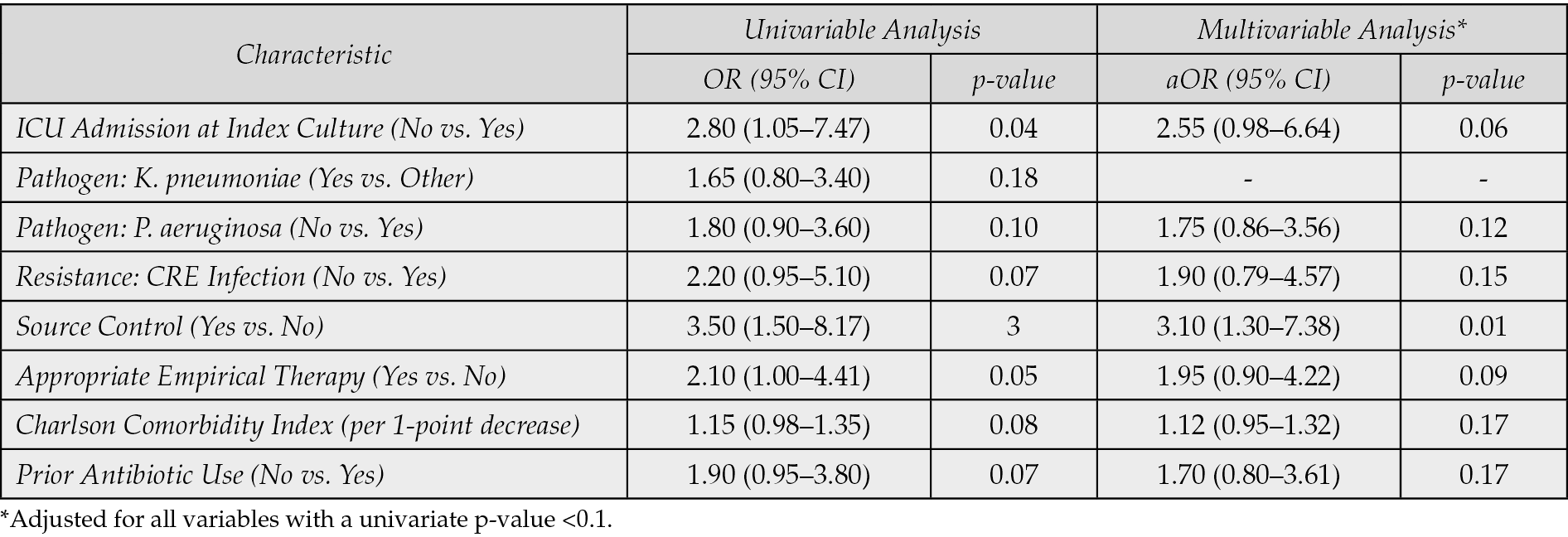

To identify patient and treatment characteristics independently associated with achieving clinical success (as opposed to failure), we performed univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses, with the results summarized in Table 8. In the univariable analysis, factors associated with a higher odds of clinical success included appropriate empirical therapy (OR: 2.10; 95% CI: 1.00–4.41; p=0.05), achieving source control (OR: 3.50; 95% CI: 1.50–8.17; p=0.003), and lower baseline comorbidity (represented by Charlson Comorbidity Index, p=0.08). Specific individual comorbidities (including hypertension, heart failure, diabetes, and others such as chronic kidney disease, malignancy, or chronic liver disease) were not included as separate variables in the final multivariable models (Tables 7 and 8). Many comorbidities are highly correlated with each other and with overall illness severity and thus, including multiple highly correlated individual comorbidities can lead to multicollinearity, which inflates standard errors and makes the interpretation of individual coefficients unstable. Factors indicative of severe illness, such as ICU admission, showed a significant negative association with success. After adjusting for variables with a univariate p<0.1, source Control remained the strongest independent predictor of clinical success (aOR: 3.10; 95% CI: 1.30–7.38; p=0.01). Additionally, receiving appropriate empirical therapy showed a strong trend towards independently predicting success (aOR: 1.95; 95% CI: 0.90–4.22; p=0.09). While ICU admission demonstrated a strong negative trend (p=0.06), the association was not independently significant in the final model, suggesting the effects of severity are partially captured by the other factors in the model. The odds of success trended lower for infections caused by CRE and P. aeruginosa, though neither reached independent significance, highlighting IMI/REL’s baseline efficacy against these targeted pathogens.

Table 6 - Efficacy and Mortality Outcomes Stratified by Pathogen, Resistance Phenotype, and Illness Severity in Patients with Gram-Negative Bacteraemia Treated with Imipenem/Cilastatin/Relebactam (n=195)

Table 7 - Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis for Factors Associated with 30-Day All-Cause Mortality (n=195)

Table 8 - Univariable and Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis for Factors Associated with Clinical Success (n=195).

DISCUSSION

This retrospective analysis provides valuable real-world evidence on the efficacy and safety of imipenem/cilastatin/relebactam for the treatment of Gram-negative bacteremia. The findings of this study – a clinical success rate of 72.82% and a 30-day all-cause mortality rate of 11.3% - are highly encouraging and align well with the limited but growing body of literature on this agent. Our stratified analyses revealed that patient outcomes were strongly influenced by disease severity, with critically ill patients admitted to the ICU exhibiting significantly lower clinical success (57.7%) and higher 30-day mortality (23.1%) compared to non-ICU patients. IMI/REL showed robust efficacy against key DTR pathogens, achieving a clinical success rate of 70.73% against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and 79.17% against Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. Moreover, efficacy was maintained against carbapenem-non-susceptible isolates (68.4% clinical success) and specifically CRE (65.2% clinical success). IMI/REL was generally well-tolerated, with adverse drug reactions observed in only 4.1% of patients, leading to discontinuation in a mere 1.02% of cases.

The clinical success rate observed in our cohort (72.82%) is comparable to the 70.2% success rate reported in a real-world, multicentre observational study of 151 patients with GNB infections treated with IMI/REL [11]. That study also noted that factors such as heart failure, prior antibiotic use, and ICU admission were associated with reduced odds of clinical success [11]. Our real-world findings contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting the application of IMI/REL in challenging clinical scenarios, particularly in settings like the ICU where the burden of MDR infections is particularly severe [12]. Effective management strategies in these environments are increasingly exploring not only targeted antimicrobial deployment but also innovative microbial ecological approaches, such as repopulating beneficial microbiota, to combat MDR threats [13]. The judicious use of IMI/REL, informed by local epidemiology and rapid diagnostics, is thus a crucial component of a comprehensive strategy against escalating resistance [13]. Our cohort, characterized by a high comorbidity burden (median Charlson score of 4) and significant illness severity (median APACHE II score of 14), mirrors the complexity of the patient population in which IMI/REL is typically used. The clinical outcomes also compare favourably with those reported for other newer β-lactam /β-lactamase inhibitor combinations in similar patient populations [14, 15]. For instance, studies on ceftazidime/avibactam (CAZ/AVI) for CRE infections have reported clinical success rates of 59% and 65% in severely ill cohorts, as well as a 71% clinical success rate in another study [16-18]. In contrast, a study on CAZ/AVI for a less resistant, non-CRE population found a higher clinical success rate of 90.5% [19]. A real-world study on meropenem/vaborbactam (MER/VAB) found a clinical success rate of 77% and other retrospective analyses of MER/VAB reported success rates ranging from 60% to 75% [20-22]. Ceftolozane/tazobactam (C/T) has shown a clinical success rate of 62.4% in a high-acuity patient population and 72.6% in a systematic review of cases involving drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa respiratory infections [23, 24].

The low 30-day all-cause mortality rate of 11.3% in our study compares favourably with outcomes reported for other newer agents. The MER/VAB real-world study reported a 30-day mortality rate of 15.4% [25]. Studies on CAZ/AVI for CRE infections reported higher mortality rates, ranging from 24% to 35% and 32% in-hospital mortality [26-28]. A retrospective study on C/T for MDR GNB infections noted a 30-day mortality rate of 17.3% [29]. These comparisons underscore the potential of IMI/REL to improve survival in patients with severe GNB infections.

The efficacy of IMI/REL is rooted in its unique mechanism of action. Relebactam’s ability to inhibit Ambler Class A and C β-lactamases restores the activity of imipenem against pathogens that produce KPCs and AmpCs [30]. The high prevalence of P. aeruginosa (63.1%) and K. pneumoniae (24.6%) in our cohort, coupled with the high rate of carbapenem-non-susceptibility, provides a clear rationale for the use of IMI/REL. The fact that the most common β-lactamases identified in a subset of our isolates were KPC and AmpC further supports the targeted use of this agent. The literature also suggests that IMI/REL retains activity against some CRE and DTR P. aeruginosa isolates that are resistant to other newer β-lactams, highlighting the importance of susceptibility testing to guide therapy [31]. Resistance to IMI/REL can still emerge, often mediated by chromosomal factors such as the loss of outer membrane porins (OmpK35 and OmpK36) or through AmpC overexpression [32]. Our patient cohort exhibited a high rate of prior antibiotic exposure, with 78.8% of patients having received antibiotics in the 30 days preceding the index culture. This high prevalence underscores the significant selection pressure that contributes to the DTR status of the pathogens studied. While prior antibiotic use trended towards being negatively associated with clinical success in univariate analysis, it did not emerge as an independent predictor in the final multivariate model. This suggests that the ultimate success of IMI/REL therapy and patient survival were more dominantly influenced by acute, modifiable factors (like achieving effective source control) and inherent patient severity (captured by ICU admission) than by the history of prior antibiotic exposure alone. Nonetheless, the high rate of prior use remains a core characteristic of populations requiring these last-line agents and confirms their high baseline risk for complicated outcomes.

The safety profile observed in our study was consistent with the known adverse effects of IMI/REL [33, 34]. The overall rate of adverse drug reactions was low (4.1%), with only a minimal number of patients requiring discontinuation. This is in line with clinical trial data, which have shown that IMI/REL is generally well tolerated, with the most common adverse events being gastrointestinal, along with potential for central nervous system effects such as seizures, particularly in patients with pre-existing conditions or renal impairment [35].

The findings of this study must be viewed within the context of global antibiotic stewardship efforts. Major infectious disease societies, such as the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), recommend reserving newer BL/BLIs for severe infections caused by extensively resistant bacteria [36]. This is a crucial strategy to prevent the rapid emergence of resistance to these valuable new agents. The use of IMI/REL in our cohort for bacteraemia, a life-threatening condition, aligns with this guidance. Our findings confirm that the use of IMI/REL aligns also closely with global antibiotic strategies to combat AMR. As a critical therapeutic option, IMI/REL addresses the need to develop new medicines by effectively treating infections caused by critical priority pathogens like KPC-producing Enterobacterales and resistant P. aeruginosa. Furthermore, the prudent use of IMI/REL supports the pillar of optimizing antimicrobial usage. Its reliable efficacy allows for targeted salvage therapy in patients who have failed prior regimens (demonstrated by our 60.8% success rate in this high-risk subgroup) and facilitates regimen consolidation, enabling the discontinuation of unnecessary toxic or broad-spectrum combination agents. By providing a highly effective treatment against these severe DTR-GNB, IMI/REL is a vital tool contributing to the global goal of reducing mortality and morbidity associated with drug-resistant infections in high-acuity settings. While the cost of newer BL/BLI combinations is a significant consideration, cost-effectiveness analyses provide a more nuanced perspective. Studies have demonstrated that despite their high price, these agents can be cost-effective compared to older, more toxic alternatives like colistin, due to improved clinical outcomes, reduced mortality, and fewer adverse events such as acute kidney injury [34-38]. The significant use of inhaled and systemic colistin in our study, even alongside IMI/REL-susceptible pathogens, was driven by specific clinical and microbiological imperatives in our high-resistance setting. Colistin was primarily retained as part of empiric wider coverage protocols for critically ill patients until definitive susceptibility was known, or to specifically target co-infecting pathogens outside the IMI/REL spectrum, such as Metallo-β-Lactamase (MBL)-producing organisms or Acinetobacter baumannii. Furthermore, inhaled colistin was frequently used as an adjuvant therapy in VAP cases to enhance local drug concentration at the site of infection. Our study’s finding of a low mortality rate further supports the value proposition of IMI/REL, as it can lead to reduced hospital stays and lower overall healthcare costs associated with treatment failure.

The retrospective design of this study, while providing real-world insights, has inherent limitations. The absence of a control group makes it impossible to compare IMI/REL directly to other therapies, and the potential for selection bias and confounding factors cannot be fully eliminated. Furthermore, the molecular mechanisms of resistance were only characterized in a subset of isolates, limiting a more granular analysis of treatment outcomes based on specific β-lactamase types. The retrospective nature of the study may also lead to gaps in data collection, such as missing information on patient outcomes beyond the 30-day mark. The single-center design of this study, while providing robust real-world insights from a high-acuity setting, is an inherent limitation. The specific local prevalence of resistance mechanisms (e.g., KPC and AmpC types) and institutional prescribing practices may influence outcomes, thus limiting the direct generalizability of these findings to other diverse geographical and healthcare settings.

Despite these limitations, this study provides a robust dataset that can be used to inform clinical practice and guide future research. Future prospective studies and head-to-head trials with other newer agents are needed to further define the optimal role of IMI/REL in the treatment of GNB bacteraemia [39]. As the AMR crisis continues to evolve, continuous surveillance and a deep understanding of real-world outcomes will be essential for preserving the effectiveness of our most valuable antibiotics. Furthermore, looking to the future, new Artificial Intelligence (AI) models are poised to revolutionize the combat against AMR by leveraging real-world data for the accelerated discovery and development of novel antimicrobial compounds [40]. These advanced computational approaches offer promising avenues for identifying new targets and optimizing drug candidates, thereby complementing and expanding upon traditional antimicrobial research efforts to address the urgent need for new therapies [40]

In this retrospective analysis of 195 patients with Gram-negative bacteraemia, IMI/REL demonstrated a high clinical success rate and a low 30-day mortality rate, reinforcing its potential as a highly effective and well-tolerated treatment option. The findings of this study, particularly in a complex patient population with a high burden of comorbidities and resistant pathogens, align with and expand upon the existing literature. As a crucial component of the strategy to combat AMR, IMI/REL should be reserved for severe infections with limited treatment options. The evidence presented here provides a strong foundation for future research and contributes to a more informed approach to the management of life-threatening infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, V.P. and P.P.; methodology, V.P.; software, V.P.; formal analysis, V.P.; investigation, V.P., K.K., P.K., P.R., M.P., T.K., N.B.; resources, V.P.; data curation, V.P.; writing - original draft preparation, V.P.; writing–review and editing, V.P, P.P., D.P..; visualization, V.P.; supervision, V.P., P.P.; project administration, P.P., V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University General Hospital of Alexandroupolis and Democritus University of Thrace.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

REFERENCES

[1] Price R. O’Neill report on antimicrobial resistance: funding for antimicrobial specialists should be improved. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2016; 23(4): 245-247. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-001013.

[2] Chelkeba L, Melaku T, Mega TA. Gram-Negative Bacteria Isolates and Their Antibiotic-Resistance Patterns in Patients with Wound Infection in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Infect Drug Resist. 2021; 14: 277-302. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S289687.

[3] Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022; 399(10325): 629-655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0.

[4] Sader HS, Castanheira M, Duncan LR, Mendes RE. Antimicrobial activities of ceftazidime/avibactam, ceftolozane/tazobactam, imipenem/relebactam, meropenem/vaborbactam, and comparators against Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with skin and soft tissue infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2021; 113: 279-281. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.10.022.

[5] Durante-Mangoni E, Bertolino L, Mastroianni C, et al. Complicated carbapenem-resistant infections: a treatment pathway analysis in Italian sites. Infez Med. 2021; 29(3): 434-449. doi: 10.53854/liim-2903-15.

[6] Caniff KE, Rebold N, Xhemali X, et al. Real-World Applications of Imipenem-Cilastatin-Relebactam: Insights From a Multicenter Observational Cohort Study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2025 Feb 26;12(4):ofaf112. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaf112

[7] Sansone P, Giaccari LG, Di Flumeri G, et al. Imipenem/Cilastatin/Relebactam for Complicated Infections: A Real-World Evidence. Life (Basel). 2024; 14(5): 614. doi: 10.3390/life14050614.

[8] Zhanel GG, Lawrence CK, Adam H, et al. Imipenem-Relebactam and Meropenem-Vaborbactam: Two Novel Carbapenem-β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations. Drugs. 2018; 78(1): 65-98. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0851-9.

[9] Vena A, Giacobbe DR, Castaldo N, et al. Clinical Experience with Ceftazidime-Avibactam for the Treatment of Infections due to Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria Other than Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020; 9(2): 71. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9020071.

[10] Karlowsky JA, Kazmierczak KM, Bouchillon SK, de Jonge BLM, Stone GG, Sahm DF. In Vitro Activity of Ceftazidime-Avibactam against Clinical Isolates of Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Collected in Latin American Countries: Results from the INFORM Global Surveillance Program, 2012 to 2015. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019; 63(4): e01814-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01814-18.

[11] Lob SH, Hackel MA, Young K, Motyl MR, Sahm DF. Activity of imipenem/relebactam and comparators against gram-negative pathogens from patients with bloodstream infections in the United States and Canada - SMART 2018-2019. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021; 100(4): 115421. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2021.115421.

[12] Caniff KE, Rebold N, Xhemali X, et al. Real-World Applications of Imipenem-Cilastatin-Relebactam: Insights From a Multicenter Observational Cohort Study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2025; 12(4): ofaf112. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaf112.

[13] Temsah MH, Al-Tawfiq JA. Repopulate, not just decolonise-a microbial ecological strategy against multidrug resistance in intensive care units. Lancet Microbe. 2025; 101206. doi: 10.1016/j.lanmic.2025.101206.

[14] Carpenter J, Neidig N, Campbell A, et al. Activity of imipenem/relebactam against carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae with high colistin resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019; 74(11): 3260-3263. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz354.

[15] Smith JR, Rybak JM, Claeys KC. Imipenem-Cilastatin-Relebactam: A Novel β-Lactam-β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combination for the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Pharmacotherapy. 2020; 40(4): 343-356. doi: 10.1002/phar.2378.

[16] Mansour H, Ouweini AEL, Chahine EB, Karaoui LR. Imipenem/cilastatin/relebactam: A new carbapenem β-lactamase inhibitor combination. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021; 78(8): 674-683. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxab012.

[17] Campanella TA, Gallagher JC. A Clinical Review and Critical Evaluation of Imipenem-Relebactam: Evidence to Date. Infect Drug Resist. 2020; 13: 4297-4308. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S224228.

[18] Lucasti C, Vasile L, Sandesc D, et al A. Phase 2, Dose-Ranging Study of Relebactam with Imipenem-Cilastatin in Subjects with Complicated Intra-abdominal Infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016; 60(10): 6234-43. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00633-16.

[19] Hirsch EB, Ledesma KR, Chang KT, Schwartz MS, Motyl MR, Tam VH. In vitro activity of MK-7655, a novel β-lactamase inhibitor, in combination with imipenem against carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012, 56: 3753–3757. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05927-11.

[20] Mavridou E, Melchers RJ, van Mil AC, Mangin E, Motyl MR, Mouton JW. Pharmacodynamics of imipenem in combination with β-lactamase inhibitor MK7655 in a murine thigh model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015 Feb;59(2):790-5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03706-14.

[21] Abniki R, Tashakor A, Masoudi M, Mansury D. Global Resistance of Imipenem/Relebactam against Gram-Negative Bacilli: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2023; 100: 100723. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2023.100723

[22] Machuca I, Dominguez A, Amaya R, et al. Real-World Experience of Imipenem-Relebactam Treatment as Salvage Therapy in Difficult-to-Treat Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections (IMRECOR Study). Infect Dis Ther. 2025; 14(1): 283-292. doi: 10.1007/s40121-024-01077-z.

[23] Kaye KS, Boucher HW, Brown ML, et al. Comparison of Treatment Outcomes between Analysis Populations in the RESTORE-IMI 1 Phase 3 Trial of Imipenem-Cilastatin-Relebactam versus Colistin plus Imipenem-Cilastatin in Patients with Imipenem-Nonsusceptible Bacterial Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020; 64(5): e02203-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02203-19.

[24] Titov I, Wunderink RG, Roquilly A, et al. A Randomized, Double-blind, Multicenter Trial Comparing Efficacy and Safety of Imipenem/Cilastatin/Relebactam Versus Piperacillin/Tazobactam in Adults With Hospital-acquired or Ventilator-associated Bacterial Pneumonia (RESTORE-IMI 2 Study). Clin Infect Dis. 2021; 73(11): e4539-e4548. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa803.

[25] Rebold N, Morrisette T, Lagnf AM, et al. Early Multicenter Experience With Imipenem-Cilastatin-Relebactam for Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021; 8(12): ofab554. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab554.

[26] Bassetti M, Echols R, Matsunaga Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of cefiderocol or best available therapy for the treatment of serious infections cfaused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (CREDIBLE-CR): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, pathogen-focused, descriptive, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021; 21(2): 226-240. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30796-9.

[27] Shields RK, Stellfox ME, Kline EG, Samanta P, Van Tyne D. Evolution of Imipenem-Relebactam Resistance Following Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2022; 75(4): 710-714. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac097.

[28] Fraile-Ribot PA, Zamorano L, Orellana R, et al. GEMARA-SEIMC/REIPI Pseudomonas Study Group. Activity of Imipenem-Relebactam against a Large Collection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolates and Isogenic β-Lactam-Resistant Mutants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020; 64(2): e02165-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02165-19.

[29] Gomis-Font MA, Cabot G, Sánchez-Diener I, et al. In vitro dynamics and mechanisms of resistance development to imipenem and imipenem/relebactam in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020; 75(9): 2508-2515. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa206.

[30] Young K, Painter RE, Raghoobar SL, et al. In vitro studies evaluating the activity of imipenem in combination with relebactam against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Microbiol. 2019 Jul 4;19(1):150. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1522-7.

[31] Tiseo G, Stefani S, Fasano FR, Falcone M. The burden of infections caused by Metallo-Beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales in Italy: epidemiology, outcomes, and management. Infez Med. 2025; 33(3): 249-260. doi: 10.53854/liim-3303-1.

[32] Meletis G, Vavatsi N, Exindari M, et al. Accumulation of carbapenem resistance mechanisms in VIM-2-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa under selective pressure. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014; 33(2): 253-258. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1952-3.

[33] Livermore DM. Interplay of impermeability and chromosomal beta-lactamase activity in imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992; 36: 2046–2048. doi: 10.1128/AAC.36.9.2046.

[34] Hoban DJ, Lascols C, Nicolle LE, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Enterobacteriaceae, including molecular characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing species, in urinary tract isolates from hospitalized patients in North America and Europe: results from the SMART study 2009-2010. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012; 74(1): 62-7. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.05.024.

[35] O’Donnell JN, Lodise TP. New Perspectives on Antimicrobial Agents: Imipenem-Relebactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022; 66(7): e0025622. doi: 10.1128/aac.00256-22.

[36] Lasarte-Monterrubio C, Fraile-Ribot PA, Vázquez-Ucha JC, et al. Activity of cefiderocol, imipenem/relebactam, cefepime/taniborbactam and cefepime/zidebactam against ceftolozane/tazobactam- and ceftazidime/avibactam-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2022; 77(10): 2809-2815. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkac241.

[37] Balibar CJ, Grabowicz M. Mutant alleles of lptD increase the permeability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and define determinants of intrinsic resistance to antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016; 60: 845–854. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01747-15.

[38] Ozma MA, Abbasi A, Asgharzadeh M, et al. Antibiotic therapy for pan-drug-resistant infections. Infez Med. 2022; 30(4): 525-531. doi: 10.53854/liim-3004-6.

[39] Al-Tawfiq JA, Sah R, Mehta R, Apostolopoulos V, Temsah MH, Eljaaly K. New antibiotics targeting Gram-negative bacilli. Infez Med. 2025; 33(1): 4-14. doi: 10.53854/liim-3301-2.

[40] Rabaan AA, Alhumaid S, Mutair AA, et al. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Combating High Antimicrobial Resistance Rates. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022; 11(6):784. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11060784.