Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 4, 413-421, 2025

doi: 10.53854/liim-3304-6

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Halfway between Cure and Care: Suppressive Therapy in Inoperable Infective Endocarditis

Sergio Venturini1, Ingrid Reffo2, Laura Munaretto3, Alessio Della Mattia3, Giovanni Del Fabro1, Astrid Callegari1, Agnese Zanus-Fortes1, Federico Giovagnorio1, Daniela Pavan3

1 Department of Infectious Diseases, ASFO “Santa Maria degli Angeli” Hospital of Pordenone, Pordenone, Italy;

2 Department of Anesthesiology, ASFO “Santa Maria dei Battuti” Hospital of San Vito al Tagliamento, Pordenone, Italy;

3 Department of Cardiology, ASFO “Santa Maria degli Angeli” Hospital of Pordenone, Pordenone, Italy.

Article received 12 September 2025 and accepted 24 October 2025

Corresponding author

Ingrid Reffo

E-mail: ingrid.reffo@asfo.sanita.fvg.it

SUMMARY

Background: Infective endocarditis (IE) is a high-mortality condition that requires multidisciplinary expertise. In elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, surgery is often precluded by prohibitive risks or technical difficulties, leading to poor patient outcomes. Long-term suppressive antimicrobial therapy (SAT) is an alternative approach aimed at reducing relapse risk and maintaining clinical stability, with limited but growing evidence.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective, single-center observational study in northeastern Italy, that included 34 adult patients diagnosed with IE from January 1, 2020, to July 31, 2024. These patients were managed with SAT after completing a standard intravenous antimicrobial course and were either ineligible for curative surgery or had experienced failed surgical intervention, as determined by the Multidisciplinary Endocarditis Team (MET). The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality at the last available follow-up and documented infection relapse. Secondary outcomes included SAT characteristics (treatment duration, type of antimicrobial agent, discontinuation and its causes, and clinical course), as well as the occurrence of adverse drug events (ADEs) or tolerance issues attributable to SAT.

Results: The median age was 77 years (IQR 67-82), and the median Charlson Comorbidity Index was 6 (IQR 5–8). Prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) was the most common presentation, affecting 24 patients (70.6%). The blood culture positivity rate was 88.2%, with the main isolated microorganisms including staphylococci (13, 40.6% – mostly methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus – MSSA), streptococci (11, 34.4%), and Enterococcus faecalis (6, 18.8%). All-cause mortality during follow-up was 5/34 (14.7%), and the relapse rate was 4/34 (11.8%), all occurring during treatment. Median follow-up was 845 days (IQR 446–1488). ADEs affected 6/34 patients (17.6%), resulting in one hospitalization but without requiring treatment suspension. SAT was terminated by MET decision in 12 patients, with no subsequent relapses.

Conclusions: In non-operable IE patients, SAT has proven to be a feasible long-term strategy, weighing the risks of recurrence, drug-related events, and prolonged antibiotic exposure. Careful patient selection and strict follow-up are crucial.

Keywords: infective endocarditis, prosthetic valve endocarditis, suppressive antimicrobial therapy, multidisciplinary endocarditis team.

INTRODUCTION

The management of infective endocarditis (IE) remains one of the most demanding challenges in infectious diseases, especially when the standard curative approach – targeted antimicrobial therapy and cardiac surgery when indicated – is not feasible [1-3]. In such situations, clinicians are often forced to operate within a zone of therapeutic uncertainty, balancing the risks of infection relapse and progression against the patient’s frailty and the impracticality of surgical intervention [4, 5]. These cases raise not only clinical but also ethical and prognostic questions, requiring individualized decisions within a multidisciplinary framework [4-7].

While antimicrobial therapy alone may be sufficient in selected cases of native-valve IE (NVE), the treatment of prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) or cardiac implantable electronic device-related IE (CIED-IE) usually requires the complete removal of infected material alongside prolonged antibiotic therapy [1, 2, 7, 8]. Unfortunately, a growing number of patients are not suitable for surgery due to advanced age or comorbidities [3, 5, 8]. As highlighted by the EURO-ENDO registry, indicated but unperformed surgery is an independent risk factor for poor outcomes, including higher mortality and infection relapse [2, 6, 7]. In this high-risk context, suppressive antimicrobial therapy (SAT) is emerging as an effective option with a palliative rather than curative goal. SAT is defined as the prolonged or indefinite use of antibiotics after initial intravenous treatment to control infection in patients in whom the initial treatment failed to eradicate the infection and in whom surgical risks are deemed unaffordable [3, 5, 10, 11, 13].

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has recently included SAT as potential option for PVE not undergoing surgery, fungal IE, or incomplete removal of an infected device [2, 6]. SAT has been used in patients with prosthetic material (e.g., prosthetic heart valves, vascular grafts, CIED) with ongoing infection or high risk of relapse, when the causative organism is susceptible to oral agents and the patient is clinically stable after initial intravenous therapy [3, 9, 11-15]. SAT is also mentioned by American Heart Association (AHA) (endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America – IDSA) and European Society of Cardiology (ESC) as an option in patients with extensive paravalvular infection, abscess, or persistent bacteremia in select cases [1, 4, 8, 10].

However, the specific parameters of this setting are yet to be defined. In particular, the role of nuclear imaging techniques – such as 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) and White Blood Cell Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography/Computed Tomography (WBC-SPECT/CT) – and treatment surveillance modalities remain unclear [2, 3, 5, 11]. There are significant uncertainties surrounding the optimal selection of antimicrobial agents, especially in light of emerging strategies and newer molecules being explored in similar clinical scenarios (e.g., prosthetic joint and vascular graft infections) [15, 16]. Additionally, the frailty and considerable burden of polypharmacy in these patients present substantial challenges to the safety, tolerability, and adherence to long-term antibiotic regimens [10-14]. Lastly, the potential emergence of multidrug-resistant organisms raises clinical and public health concerns regarding prolonged antibiotic use [3, 10, 12, 13].

To contribute to the limited evidence base, we conducted a retrospective single-center study to examine the clinical characteristics, therapeutic indications, and outcomes of patients with IE who received long-term suppressive antibiotic therapy in a non-curative context.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a retrospective, observational study at Pordenone and San Vito al Tagliamento Hospitals, located in the Friuli Venezia Giulia region of northeastern Italy. Eligible cases were identified through a review of medical records from January 1, 2020, to July 31, 2024. This approach aims to ensure a minimum follow-up period of 12 months.

Study Population

We included adult patients (18 years or older) diagnosed with infective endocarditis (IE) according to the 2023 ESC criteria who were considered suitable for the SAT approach after assessment by the Multidisciplinary Endocarditis Team (MET), which comprises cardiologists, infectious disease specialists, and cardiac surgeons. Eligible patients included those with a confirmed surgical indication but deemed inoperable due to high perioperative risks related to comorbidities or technical constraints, patients who refused surgery, and those who had an initial surgical attempt that was not curative, provided all patients completed a full four- to six-week course of intravenous antimicrobial therapy. In cases of multiple IE episodes, only the episode for which the MET had formally recommended SAT was retained. We excluded patients who underwent curative surgery during or after completing initial antimicrobial therapy.

Definitions and Data Collection

Baseline variables collected included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and comorbidities, as measured by the age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). Chronic kidney disease was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m², using the CKD-EPI formula according to the KDIGO classification (Grade G3a). Infection-related data included the presence of prosthetic heart valves or CIEDs, imaging findings (such as transthoracic echocardiograms – TTE – and transesophageal echocardiograms, and PET/CT scans, if available), and microbiological documentation.

Recorded data included the length of antimicrobial treatment, the antimicrobial used, the duration of SAT, the occurrence of adverse drug events (ADEs), mortality during follow-up, and tolerance issues.

Monitoring protocol

According to our local MET protocol, patients undergoing SAT are scheduled for evaluations at 6 and 12 months after starting treatment, and then every 6 to 12 months based on the treating cardiologist’s recommendation. These evaluations include a cardiology consultation and TTE, with TEE if considered necessary, every 6-12 months; infectious disease consultations at each time point; and laboratory tests, such as complete blood count, creatinine/eGFR, liver enzymes, and C-reactive protein levels, every 30 to 40 days throughout treatment. Additionally, a PET/CT scan is performed during the acute phase or soon after initiation of SAT, and then at 6-12 months, depending on clinical evolution and imaging results. Further investigations are conducted at the discretion of the treating cardiologist. Unscheduled visits are prompted by new or worsening symptoms (such as fever, signs of heart failure, or embolic phenomena) or abnormal test results.

Criteria for SAT discontinuation. Discontinuation of SAT is considered after at least six months if all of the following criteria are met:

1) persistently negative blood cultures;

2) stable, non-progressive echocardiographic findings (TTE/TEE);

3) no abnormal metabolic activity on follow-up ^18F-FDG PET/CT (when performed);

4) clinical stability without new or worsening IE-related symptoms; and

5) persistently low inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., CRP), as determined by the treating team.

Final decisions regarding discontinuation are made by infectious diseases (ID) specialists.

Follow-up, Outcomes, and Definitions

Follow-up is defined from the start of SAT until the earliest of the following events: death; SAT discontinuation; microbiologically confirmed relapse; clinical failure; loss to follow-up; or the last available clinical assessment (right-censoring). For patients who discontinued SAT (planned or self-discontinued), we also recorded post-discontinuation follow-up until relapse, death, loss to follow-up, or last assessment. Follow-up time is reported as median (IQR). The most recent clinical assessment was either the last in-person hospital contact or the most recent telephone consultation.

The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality at the last follow-up and documented infection relapse. Relapse was defined as the recurrence of infective endocarditis due to the original pathogen, confirmed by at least one positive blood culture (or at least two for coagulase-negative staphylococci) after starting SAT.

Patients who suspended SAT were subsequently followed using the same protocol as for ongoing SAT patients until infectious disease specialists granted clearance.

Secondary outcomes included SAT characteristics (treatment duration, type of antimicrobial agent, reasons for discontinuation, and clinical course), as well as the occurrence of ADEs or tolerance issues attributable to SAT:

– ADEs were defined as any undesirable clinical manifestation or laboratory abnormality occurring during SAT, regardless of causality, that required medical evaluation and led to treatment modification, switch to an alternative agent, or discontinuation.

– Tolerance issues were defined as patient-reported clinical symptoms or circumstances that required minor adjustments – such as dose splitting, changing the administration schedule, or supportive care – but did not require suspension or a change in the antimicrobial agent.

– Clinical failure was defined as the presence of new or enlarging vegetations, new IE-related complications (e.g., abscess, valvular failure), or new embolic events without microbiological confirmation [17].

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. Categorical variables were shown as absolute numbers and percentages. Overall survival was calculated from the date of SAT initiation to the date of death or last follow-up.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed a general consent for the use of anonymized data for research purposes during their first MET evaluation. Since this is a retrospective study based on anonymized data, additional patient consent and ethical committee approval were not required according to national regulations.

RESULTS

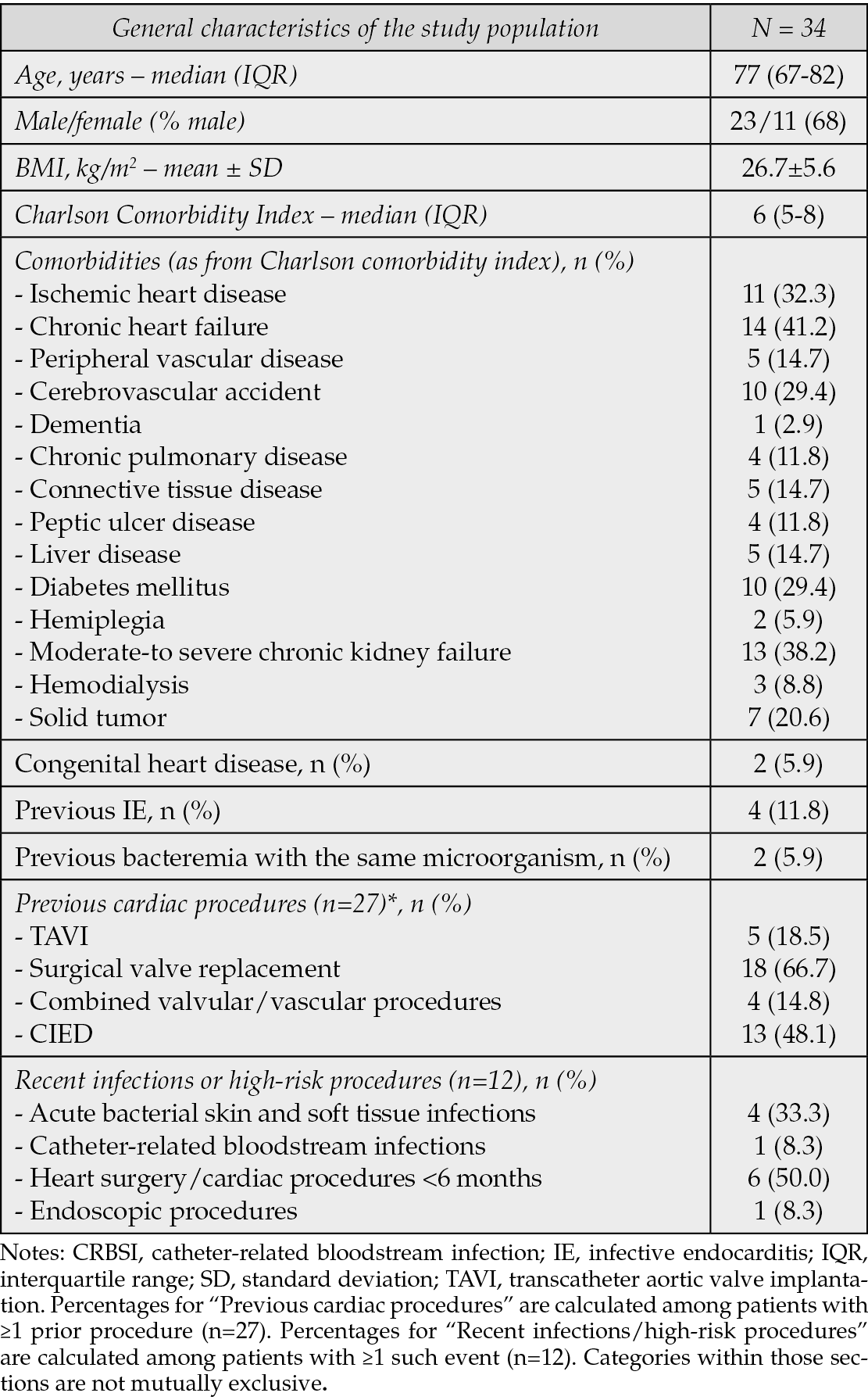

A total of 34 patients were included, with a median age of 77 years (IQR, 67–82 years), of whom 68% were male. Table 1 displays the population’s characteristics. The median age-adjusted CCI score was 6 (IQR, 5-8); the most common comorbidities were chronic heart failure, affecting 14 patients (41%), and chronic kidney disease, present in 13 patients (38%). Regarding risk factors for IE: two patients (5.9%) had congenital heart disease, four patients (11.8%) had a history of IE, and two (5.9%) experienced recent bacteremia caused by the same microorganism involved in the current IE episode. Among the 34 patients, 27 (79.4%) had a history of previous heart surgery or procedures. Specifically, five patients (14.7%) had a percutaneously inserted aortic valve (transcatheter aortic valve implantation - TAVI), 18 (53%) had a surgically implanted valve, and four patients (11.8%) had a combination of a prosthetic valve and a vascular graft. A CIED was present in 13 cases (38.2%). Additionally, twelve patients (35.3%) had a recent history (within six months) of other infectious localizations or invasive procedures at risk (see Table 1).

Table 1 - General characteristics of the study population. BMI, body mass index; CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device.

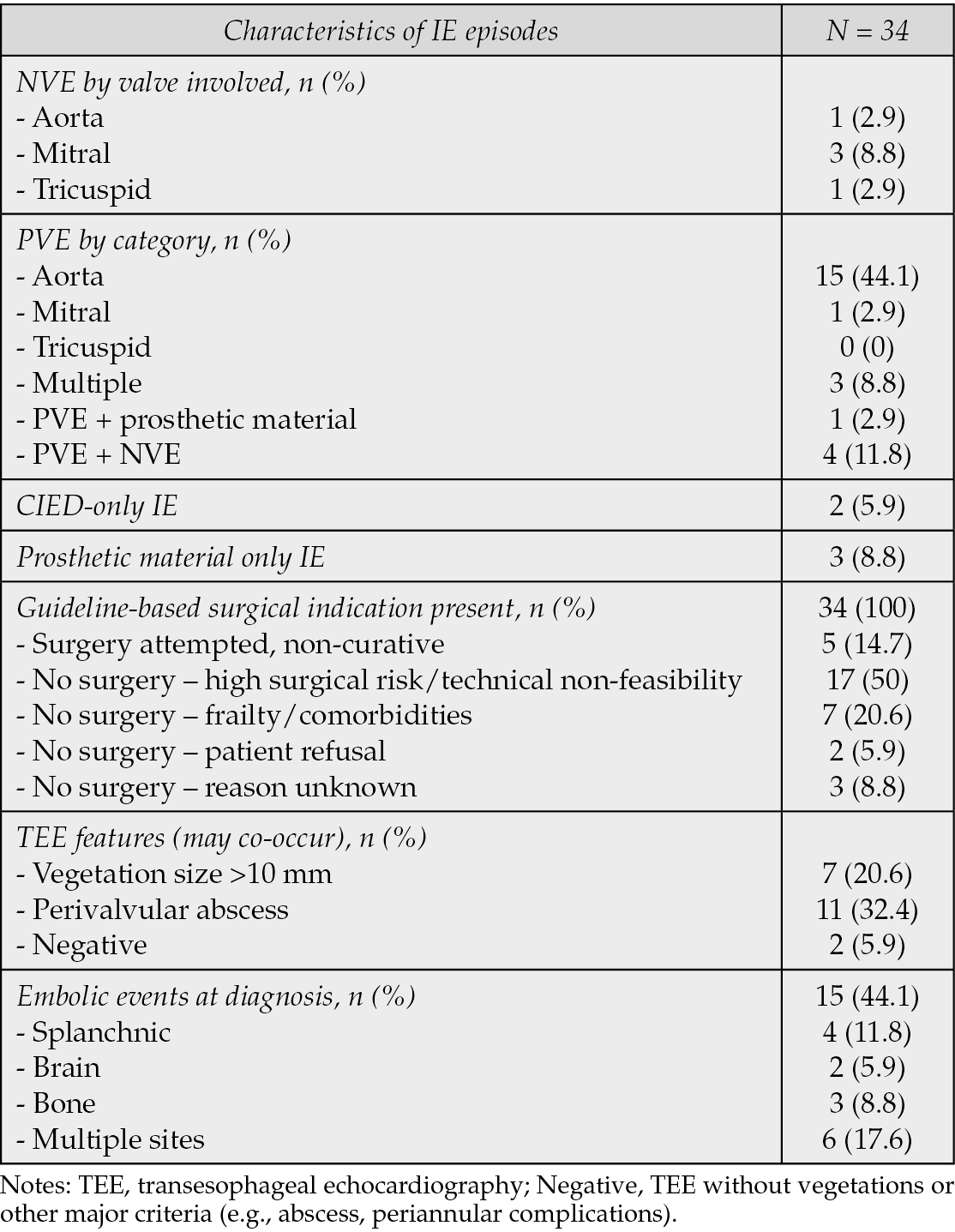

Table 2 outlines the characteristics of infections: PVE was the most prevalent, affecting 24 patients (70.6%), with 15 of these having an aortic location. Notably, 14.7% of patients had NVE, while two patients (5.9%) presented with CIED-IE, and three (8.8%) had isolated infections involving prosthetic material. All patients in this cohort were recommended for surgery; however, 29 were deemed inoperable, and in five patients (14.7%), the surgical attempt did not yield a curative outcome (as shown in Table 2). Additionally, 15 patients (44.1%) had evidence of embolization at diagnosis.

Table 2 - Characteristics of the IE episodes. NVE, native valve endocarditis; PVE, prosthetic valve endocarditis.

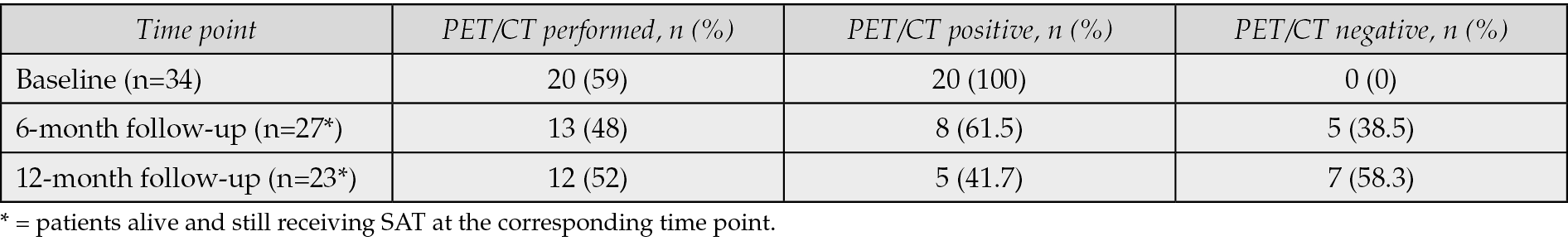

Baseline TEE was conducted for all participants. An 18F-FDG PET/CT scan was performed at baseline on 20 of 34 patients, returning positive results in all cases. Follow-up PET/CT scans at six months were completed for 13 of the 27 patients still undergoing treatment, revealing persistent metabolic activity in eight of them. At 12 months, 12 of 23 patients continuing treatment had PET/CT scans, with five exhibiting metabolic uptake (Table 3).

Table 3 - 18F-FDG PET/CT features.

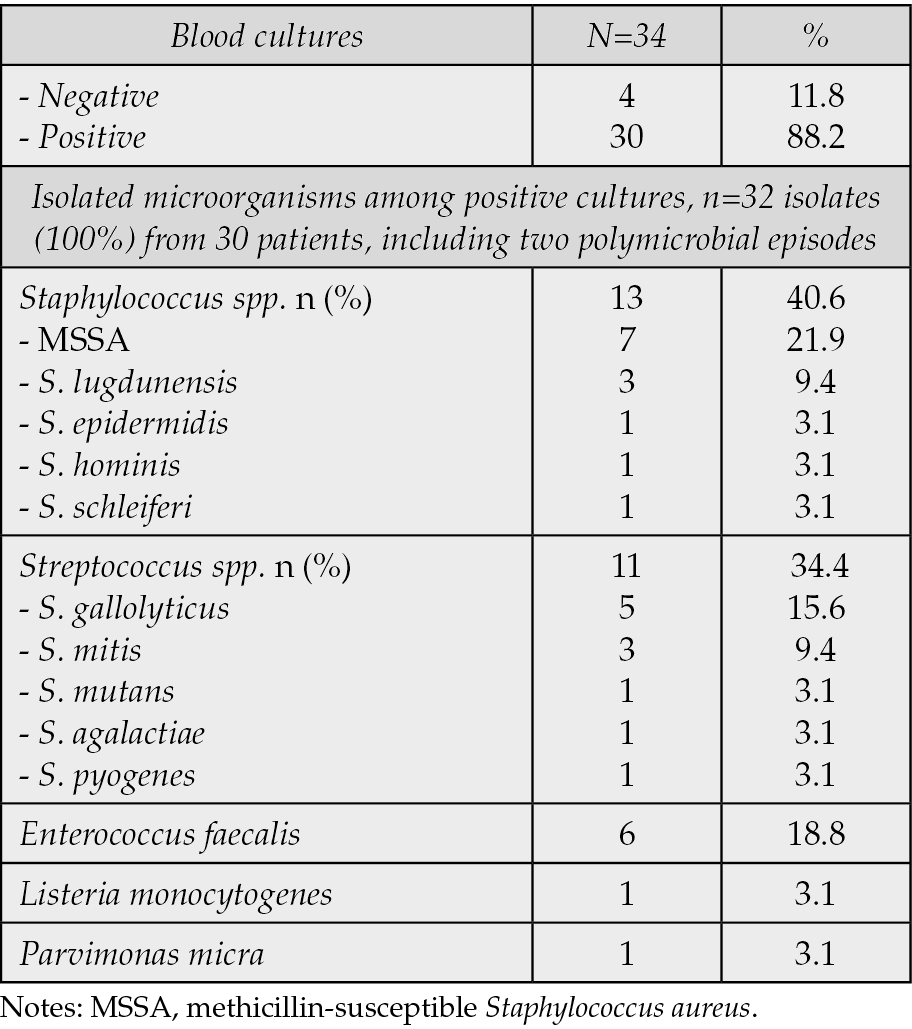

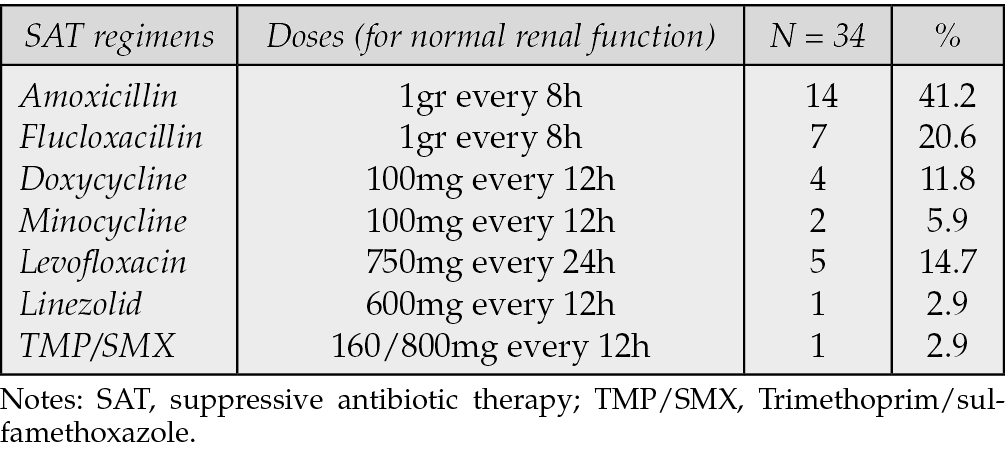

Blood cultures yielded positive results in 30 out of 34 patients (88.2%), with two episodes being polymicrobial. Notably, streptococci and enterococci comprised 53.1% of all isolates. Among the identified pathogens, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) was the most prevalent species, accounting for 21.9%, followed by Enterococcus faecalis at 18.8% and Streptococcus gallolyticus at 15.6% (Table 4). In terms of therapeutic regimens, β-lactams were the most prescribed antibiotics, administered to 21 out of 34 patients (62%), with amoxicillin being the first choice for all enterococcal IE (six out of six cases) and for eight of 11 streptococcal infections. Flucloxacillin was used for six of 13 staphylococcal infections. Tetracyclines were used for staphylococcal (four out of 13) and two streptococcal isolates. Specifically, tetracyclines were used, after microbiological confirmation of susceptibility, in one polymicrobial IE episode and in one Streptococcus mutans IE case, where doxycycline replaced levofloxacin due to suspected neurotoxicity. Levofloxacin was prescribed for four patients (Table 5). All regimens were monotherapy.

Table 4 - Microbiological features.

Table 5 - Antimicrobial regimens were defined for patients with normal renal function.

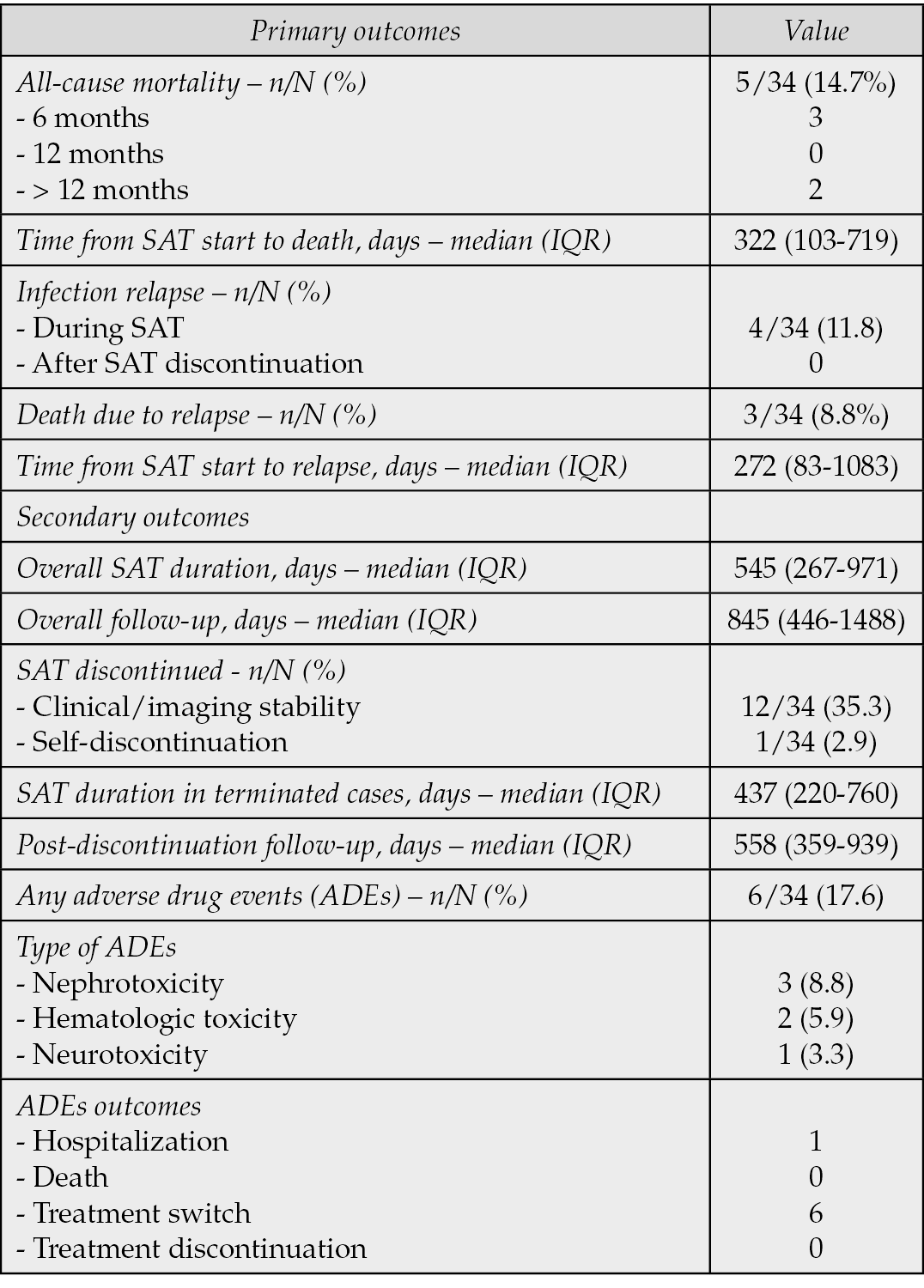

Table 6 summarizes the outcomes. Primary outcomes: five patients (14.7%) died during follow-up three within 6 months and two >1 year after starting SAT. Four deaths were cardiac, three of which were directly attributable to IE relapse. Infection relapse occurred in four patients (11.8%), resulting in death of three of them. Secondary outcomes (Table 6): the median overall follow-up was 845 days (IQR, 446–1488); the median SAT duration was 545 days (IQR, 267–971). The median time from SAT initiation to death was 322 days (IQR, 103–719), and the median time to relapse was 272 days (IQR, 83-1083). Twelve patients discontinued SAT, without any relapse to date, and follow-up for these patients is ongoing. One patient opted to self-discontinue therapy and continues to be monitored without any documented relapse thus far. ADEs associated with SAT were reported in six patients, with renal toxicity (three cases, 8.8%) being the most common, followed by myelotoxicity (two cases, 5.9%), and neurotoxicity (one case, 3.3%). Specifically, of the three patients who experienced worsening of renal function, all but one had chronic kidney failure; one of these required hospitalization. Renal toxicity was observed during treatment with amoxicillin, minocycline, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. One patient developed agranulocytosis during flucloxacillin therapy, and another experienced thrombocytopenia due to minocycline. One patient developed peripheral neuropathy from linezolid. All patients had their medications switched to a different class without discontinuing treatment. Six patients had their conditions managed at home with closer monitoring and supportive care, and no deaths attributable to SAT occurred. Additionally, eight patients experienced minor tolerance issues, including gastrointestinal intolerance due to β-lactams in four patients, mild transient skin problems in three patients receiving tetracyclines, and one case potentially related to amoxicillin. None required drug discontinuation; symptoms were managed with scheduling adjustments and supportive care.

Table 6 - Outcomes. ADEs, adverse drug events.

DISCUSSION

In our cohort, the study population was similar to those reported in other series. For instance, in the study by Lemmet et al., patients had comparable age (mean 77 years) and comorbidities, with a Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 6 [3]. Therefore, the two cohorts had similar risk profiles, although they were heterogeneous for direct comparison.

Our outcomes are consistent with recent literature, showing a 12-month survival rate of 91.2%. In 2021, Vallejo Camazon et al. reported a survival rate of 78%, while in 2017, Tan et al. reported a survival rate of 50% in their 2017 study that specifically focused on patients with CIED-related infections. Conversely, Lemmet et al. found a survival rate of 76%, which is still lower than what we observed in our investigation. In a recent study, Tillement et al. reported a primary composite endpoint of 16.7% (1-year all-cause mortality or PVE-related hospitalization) [3, 8, 14, 18].

In our study, we reported a relapse rate of 11.8%, which aligns with the rates reported by Vallejo Camazon (12.5%), Tan (18.2%), and Lemmet (9%) [3, 8, 14]. Interestingly, all relapses in our cohort occurred during antimicrobial treatment and never after treatment was discontinued. In our study, treatment was stopped only after at least six months, provided that strict criteria were met: negative blood cultures, stable and non-progressive echocardiographic findings, and absence of metabolic activity on PET/CT. Under these conditions, no relapses occurred after stopping therapy. These findings support the potential value of a structured reassessment protocol to guide the safe discontinuation of treatment. They also highlight the importance of distinguishing between relapses that occur during treatment and those that happen after it ends. Given that individual patient responses to treatment are unpredictable, careful patient stratification is necessary, along with the development of a multidisciplinary algorithm that includes skilled echocardiographic facilities and PET/CT services. In this context, the infectious disease specialist plays a pivotal role in connecting cardiology and cardiac surgery expertise while overseeing antimicrobial therapy. Notably, unlike in Lemmet’s study, all our patients had scheduled consultations with infectious disease specialists at every time point [3].

According to the 2023 ESC Guidelines, the diagnostic work-up for infective endocarditis now relies on a multimodal imaging approach, in addition to the fundamental role of transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography. Metabolic imaging techniques such as PET/CT and WBC-SPECT/CT have been added as major diagnostic criteria for IE, especially in prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) and CIED infections, as well as for detecting extracardiac sites of infection [2, 19]. Beyond its established diagnostic contribution, PET/CT is increasingly being investigated as a strategy for surveillance and therapeutic management in patients on long-term antimicrobial therapy: recent expert consensus supports FDG-PET/CT for monitoring treatment response and guiding therapy duration in cardiovascular infections, particularly when surgery isn’t feasible [20]. In CIED-IE with incomplete device removal, negative follow-up PET/CT scans permitted safe discontinuation of SAT without subsequent relapse for over two years. Similarly, Vallejo-Camazon reported favorable outcomes after PET/CT-guided termination of SAT; Beaumont found safe SAT discontinuation in a subset of patients with imaging as adjunctive aid, and Regis et al. described that a negative PET/CT strongly predicted relapse-free outcomes (median follow-up of ten months) after completing the initial treatment course [8, 11, 19, 21]. In line with these findings, in our series, SAT was discontinued in 12 patients following a negative PET/CT scan, with no relapses observed during follow-up. We plan to assess this approach prospectively. Nevertheless, some caution is warranted.

Although antimicrobial therapy decreases PET/CT sensitivity, in our cohort, all patients had baseline imaging while on antibiotics, and all scans were nevertheless positive (20/20). Additionally, the inherent limitations of PET/CT analysis in the setting of early endocarditis and native valve endocarditis should be recognized [8, 11, 19-23]. Thus, negative results did not affect the decision to initiate or continue SAT, while positive PET/CT findings were used to guide subsequent treatment. Furthermore, issues of cost, availability, and the need for specialized expertise continue to limit the widespread use of this technique. Integration with clinical judgment and other imaging modalities remains essential, as standardized protocols for timing and interpretation are not yet universally established.

Regarding secondary outcomes, our findings align with existing literature. Adverse drug events occurred in 16.6% of patients (6 out of 34), which aligns with previous reports showing ADEs rates between 12% and 18% [8, 11, 18]. Importantly, none of our patients experienced major complications. In all cases, the treatment was switched to an alternative antimicrobial regimen, and no patient discontinued their treatment.

To note, in our SAT cohort, microbiology was primarily dominated by streptococci and enterococci (53.1%), with S. gallolyticus (15.6%) and E. faecalis (18.8%). The predominance of enterococci and streptococci in our cohort further supports the epidemiological consistency of our findings with previous local data reported in the Friuli Venezia Giulia region, particularly among elderly patients, as highlighted in the prospective multicenter study by Bassetti and colleagues [24, 25]. In contrast, staphylococci, although common (40.6%), were less prominent. Our findings align with recent SAT series: the SATIE study reported E. faecalis (36%) and S. aureus (29%) among 42 patients, 95% of whom had intracardiac material; Lemmet et al. reported comparable proportions of S. aureus and enterococci (27.3% each) in their series of 22 patients. By contrast, Tan et al. described a clear staphylococcal predominance (approximately 40%, mainly CoNS and MSSA) in a CIED-IE cohort [3, 11, 13]. These differences likely reflect the high PVE rate in our cohort and local epidemiology. The higher prevalence of organisms suitable for oral β-lactam therapy in our cohort is consistent with the frequent use of amoxicillin.

Our study has several limitations. First, it is a single-center retrospective study with a relatively small sample size, although comparable to other reports in the literature. Second, the study lacks a control group, since patient selection criteria were determined by the MET. Additionally, because it is based on routinely collected data, mild drug intolerances and adverse events might have been underreported, even though patients and caregivers are usually instructed to report any concerns as much as possible.

SAT has traditionally been seen as a palliative option in managing IE when optimal strategies – such as surgery or complete removal of infected devices – are not feasible. However, with an aging population and increasing patient frailty, this approach is being considered with growing frequency. For this reason, there is an urgent need to generate more substantial evidence and to design larger studies capable of providing definitive conclusions about the true clinical usefulness of SAT. Customizing treatment options based on individual patients’ complexity and expectations is of utmost importance in an era of personalized medicine. Establishing an appropriate control group will also be essential, as it represents a prerequisite for future investigations. Further research is needed to define long-term outcomes more precisely and identify the optimal treatment modalities.

Our findings support suppressive antimicrobial therapy (SAT) as a viable long-term option for carefully selected patients with inoperable IE. Survival outcomes were encouraging, and relapse rates remained low after discontinuation when guided by structured reassessment and PET/CT imaging. A multidisciplinary approach and personalized care are essential, and future prospective studies should aim to identify optimal regimens, treatment durations, and standardized follow-up protocols.

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest must be declared for any of the authors.

Funding

No fund was used for this study.

REFERENCES

[1] Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. American Heart Association Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and Stroke Council. Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015; 132(15): 1435-1486.

[2] Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023; 44(39): 3948-4042.

[3] Lemmet T, Bourne-Watrin M, Gerber V, et al. Suppressive antibiotic therapy for infectious endocarditis. Infect Dis Now. 2024; 54(3): 104867.

[4] Saha S, Zauner B, Schnackenburg P, et al. The role of surgery in contemporary infective endocarditis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2025; 31: ezaf259.

[5] Valsecchi P, Calia M, Giordani P, et al. Navigating troubled waters: a systematic review of prosthetic valve endocarditis reported cases treated with suppressive antimicrobial treatment. Int J Infect Dis. 2025; 158: 107934.

[6] Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021; 143(5): e35-e71.

[7] Habib G, Erba PA, Iung B, et al. EURO-ENDO Investigators. Clinical presentation, aetiology and outcome of infective endocarditis. Results of the ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO (European infective endocarditis) registry: a prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40(39): 3222-3232.

[8] Vallejo-Camazon N, Mateu L, Cediel G, et al. Long-term antibiotic therapy in patients with surgery-indicated not undergoing surgery for infective endocarditis. Cardiol J. 2021; 28(4): 566-578.

[9] Lechner AM, Pretsch I, Hoppe U, et al. Successful long-term antibiotic suppressive therapy in a case of prosthetic valve endocarditis and a case of extensive aortic and subclavian graft infection. Infection. 2020; 48(1): 133-136.

[10] Horne M, Woolley I, Lau JSY. The Use of Long-term Antibiotics for Suppression of Bacterial Infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2024; 79(4): 848-854.

[11] Beaumont AL, Mestre F, Decaux S, et al. Long-term Oral Suppressive Antimicrobial Therapy in Infective Endocarditis (SATIE Study): An Observational Study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2024; 11(5): ofae194.

[12] Bouza E, Valerio M, Mujal A, et al. Long-term suppressive therapy of infective endocarditis: clinical experience and outcomes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021; 76(11): 3018-3024.

[13] Fornari V, Accardo G, Lupia T, et al. Suppressive antibiotic treatment (SAT) in the era of MDRO infections: a narrative review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2025; 23(5): 291-303.

[14] Tan EM, DeSimone DC, Sohail MR, et al. Outcomes in Patients With Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Device Infection Managed With Chronic Antibiotic Suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2017; 64(11): 1516-1521.

[15] Chakfé N, Diener H, Lejay A, et al. Editor’s Choice - European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2020 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Vascular Graft and Endograft Infections. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2020; 59(3): 339-384.

[16] Harrabi H, Meyer E, Dournon N, et al. Suppressive Antibiotic Therapy in Prosthetic Joint Infections: A Contemporary Overview. Antibiotics (Basel). 2025; 14(3): 277.

[17] Imazio M. The 2023 new European guidelines on infective endocarditis: main novelties and implications for clinical practice. J Cardiovasc Med. 2024; 25(10): 718-726.

[18] Tillement J, Issa N, Ternacle J, et al. Antimicrobial suppressive therapy in prosthetic valve endocarditis rejected from surgery despite indication. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2025; 66(3): 107526.

[19] Hernández-Meneses M, Perissinotti A, Páez-Martínez S, et al. Hospital Clínic of Barcelona Infective Endocarditis Team Investigators. Reappraisal of [18F]FDG-PET/CT for diagnosis and management of cardiac implantable electronic device infections. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2023; 76(12): 970-979.

[20] Bourque JM, Birgersdotter-Green U, Bravo PE, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT and radiolabeled leukocyte SPECT/CT imaging for the evaluation of cardiovascular infection in the multimodality context: ASNC Imaging Indications (ASNC I2) Series Expert Consensus Recommendations from ASNC, AATS, ACC, AHA, ASE, EANM, HRS, IDSA, SCCT, SNMMI, and STS. Heart Rhythm. 2024; 21(5): e1-e29.

[21] Régis C, Thy M, Mahida B, et al. Absence of infective endocarditis relapse when end-of-treatment fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography is negative. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023; 24(11): 1480-1488.

[22] Anton CI, Munteanu AE, Mititelu MR, Alexandru Ștefan M, Buzilă CA, Streinu-Cercel A. Diagnostic Utility of 18F-FDG PET/CT in Infective Endocarditis. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(6): 1299.

[23] Pascale R, Fernández-Hidalgo N, Tazza B, et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Study Group on Implant Associated Infections (ESGIAI); European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Study Group for Bloodstream Infections, Endocarditis and Sepsis (ESGBIES). How to manage patients receiving long-term suppressive antibiotic treatment for infective endocarditis: the role of [18F]-FDG-PET/CT imaging - An international multidisciplinary survey. J Nucl Cardiol. 2025: 102505.

[24] Scudeller L, Badano L, Crapis M, Pagotto A, Viale P. Population-based surveillance of infectious endocarditis in an Italian region. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169(18): 1720-1723.

[25] Bassetti M, Venturini S, Crapis M, et al. Friuli Venezia Giulia Endocarditis study group; Piazza R, Fazio G, Di Piazza V, Maschio M, Beltrame A. Infective endocarditis in elderly: an Italian prospective multi-center observational study. Int J Cardiol. 2014; 177(2): 636-638.