Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 4, 404-412, 2025

doi: 10.53854/liim-3304-5

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

High prevalence of dengue with warning signs but absence of severe cases in Vietnamese pediatric patients: an analysis of predictive factors

Nhu Quynh Le, Hai Anh Nguyen, Khanh Huyen Vu, Khanh Linh Dang, Nang Trong Hoang, Thi Loi Dao, Van Thuan Hoang

Thai Binh University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Hung Yen, Vietnam.

Article received 23 July 2025 and accepted 17 September 2025

Corresponding authors

Thi Loi Dao

E-mail: thiloi.dao@gmail.com

Van Thuan Hoang

E-mail: thuanytb36c@gmail.com

SUMMARY

Objectives: To identify the prevalence and potential predictive factors of severe dengue among children in Vietnam.

Methods: A retrospective study was conducted at Thai Binh Pediatric Hospital, in children from 0 to 16 years, hospitalized for dengue infection from January 2023 to December 2024. Dengue severity was classified according to WHO 2009 guidelines. Potential predictive factors of severe disease were investigated using logistic regression.

Results: A total of 332 children hospitalized for dengue infection were included: median age was 14 months and male gender accounted for 63.0% of the patients. 15.1% (n=50) presented with dengue with warning sign (DWS). None of the children developed severe dengue. The mean time from symptom onset to diagnosis of DWS was 4.0 ± 2.3 days. The most common clinical manifestations in DWS cases were right upper quadrant abdominal pain (34.0%), rapid decrease in platelet count (32.0%), and hepatomegaly (26.0%).

Thrombocytopenia at admission was independent predictor (OR = 13.36, 95%CI [4.26-41.88]. Children older than five years and female patients also had higher odds of DWS (OR = 11.21, 95%CI [4.71-26.66] and OR = 2.32, 95%CI [1.05-5.13], respectively. Elevated hematocrit, hypoalbuminemia, elevated transaminases, abnormal nutritional status, petechiae and admission at ≥ 4 days from symptom onset were not associated with DWS after adjustment. The model achieved a sensitivity of 74% and a specificity of 92%, corresponding to an area under the receiver-operating-characteristic curve of 0.83, giving an overall accuracy of 89.5%.

Conclusions: Our findings identified predictive factors of DWS among children, especially low platelet count at admission is proposed as a practical tool for predicting DWS. This makes a practical tool for early risk stratification and resource allocation in settings with limited laboratory capacity in low- and middle-income countries.

Keywords: dengue, dengue with warning sign, children, predictive factors, Vietnam.

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne viral infection caused by the dengue virus, primarily transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes [1]. In children, it presents with a spectrum of clinical manifestations, ranging from mild febrile illness to severe forms such as dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome [2]. The disease is particularly significant in pediatric populations due to their unique physiological responses and potential for rapid deterioration [3].

The global burden of dengue is substantial, particularly among children, with an estimated 390 million infections annually. Of them, an approximate of 96 million are symptomatic, predominantly in Asia, Latin America, and Africa [4]. In children, severe dengue significantly contributes to hospital admissions and mortality, particularly in endemic areas. The economic burden includes both direct healthcare costs and indirect losses related to caregiver productivity. In rural settings, limited healthcare infrastructure exacerbates these challenges, underscoring the need for effective risk stratification and resource allocation to manage severe cases [5, 6]. A recent large-scale study from Colombia involving 3,611 pediatric cases highlighted the very high incidence of dengue and dengue with warning signs in children, despite ongoing public health interventions [7].

According to the 2009 WHO classification, dengue with warning signs (DWS) is defined as dengue in patients who present with one or more of the following: abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, clinical fluid accumulation, mucosal bleeding, lethargy, hepatomegaly, or an increase in hematocrit accompanied by a decrease in platelet count. Severe dengue is characterized by the presence of severe plasma leakage, severe bleeding, or severe organ impairment [8].

Previous studies on dengue in children have identified key predictors of severity. A large study in Sri Lanka validated the WHO 2009 classification by showing its high sensitivity for detecting severe manifestations such as plasma leakage and shock [9]. Similarly, studies in Bangladesh confirmed its utility in recognizing severe outcomes, including severe hemorrhage and organ involvement [10, 11]. Systematic evidence also indicates that maternal dengue infection carries high risks for both mothers and neonates, with increased rates of obstetric bleeding, preterm birth, low birth weight, and maternal and fetal mortality [12]. These findings expand the understanding of dengue’s impact beyond childhood, underscoring the need for integrated maternal-child health approaches in endemic regions. In addition, accessible clinical and laboratory markers to predict disease progression are also important for reducing the burden of dengue in children, particularly in resource-limited settings.

In Vietnam, dengue is a major public health issue, with children accounting for a significant proportion of cases [13]. Seasonal outbreaks, driven by monsoon conditions, increase mosquito breeding and disease transmission. Studies in Vietnam have reported high hospitalization rates among children, with severe dengue often associated with secondary infections and delayed healthcare access [14, 15]. The WHO 2009 warning signs, including persistent vomiting and abdominal pain, have been validated as reliable predictors of severe outcomes in Vietnamese children [16]. However, in rural settings, accurate application of these guidelines can be challenging, as persistent vomiting requires consistent observation and documentation, and abdominal pain in young children is often non-specific and difficult to interpret in the absence of advanced diagnostic support.

Research from Vietnam has added to the knowledge of dengue epidemiology and management [15, 17, 18]. A prospective study in Ho Chi Minh City identified early transcriptional signatures linked to dengue shock syndrome, highlighting immune response roles [17]. Another study emphasized daily platelet counts as a practical predictor of severe dengue, facilitating timely interventions [14]. Despite these insights, rural-focused research remains limited, with most studies conducted in urban centers, potentially overlooking unique epidemiological and clinical patterns in rural populations.

Significant knowledge gaps remain, particularly in rural Vietnamese settings. The absence of advanced biomarkers, such as serum ferritin, in these healthcare facilities limits the applicability of some prognostic approaches [19]. Variations in healthcare access, diagnostic capacity, and disease presentation in rural areas necessitate tailored risk stratification models. The interplay of clinical, laboratory, and demographic factors specific to rural Vietnamese children remains underexplored, hindering optimized management strategies.

This retrospective study, conducted in a rural Vietnamese setting, addresses these gaps by examining the epidemiology and prognostic factors of severe dengue in children. Without access to advanced biomarkers, the study focuses on widely available clinical and laboratory indicators, such as platelet counts and WHO 2009 warning signs, to identify predictors of severe disease. The objective is to generate evidence-based insights from routinely available clinical and laboratory data to support early recognition of at-risk patients, enhance clinical management, and reduce morbidity and mortality among children with dengue in resource-constrained rural areas.

METHODS

Study design and location

This retrospective study was conducted at Thai Binh Pediatric Hospital, located in Thai Binh Province, a predominantly rural region in northern Vietnam.

Thai Binh province has a population of approximately 1.8 million, with around 20% being children under 16 years of age. The province is characterized by its agricultural economy and rural communities, with limited access to advanced healthcare facilities. Thai Binh Pediatric Hospital serves as the primary referral center for pediatric care in the province, equipped with specialized units for infectious diseases and critical care, making it a suitable site for studying severe dengue cases in a rural setting. PCR testing for the diagnosis of dengue and serotype identification is not accessible at this hospital.

Study population

The study included children aged 0 to 16 years admitted to Thai Binh Pediatric Hospital between January 1, 2023, and December 31, 2024. Patients were included if they were diagnosed with dengue according to the WHO 2009 criteria, which required clinical symptoms suggestive of dengue (fever, rash, myalgia, or hemorrhagic manifestations) and laboratory confirmation by positive non-structural protein 1 (NS1) antigen and/or immunoglobulin M (IgM) serology [8]. Patients with incomplete medical records or those diagnosed with other concurrent infections were excluded.

Data collection and definition

Data were retrospectively extracted from electronic medical records of the hospital. Collected data included sociodemographic characteristics, clinical information and laboratory results, such as complete blood counts, liver function tests (transaminases), abdominal ultrasound, and chest X-rays. Dengue severity was classified according to WHO 2009 and Vietnam Ministry of Health guidelines into three categories [8, 20]:

1) Dengue without warning signs, characterized by fever and minor symptoms;

2) Dengue with warning signs (DWS), including abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, clinical fluid accumulation, mucosal bleeding, lethargy, hepatomegaly, or increasing hematocrit with decreasing platelet count, AST/ALT ≥400 IU/L; and

3) Severe dengue, defined by severe plasma leakage (leading to shock or fluid accumulation with respiratory distress), severe bleeding, or severe organ impairment (elevated liver enzymes with AST/ALT ≥1000 IU/L, impaired consciousness, or cardiac dysfunction) [8, 20].

Statistical analysis

Stata v.16.0 was used to perform statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe sociodemographic characteristics, as well as the prevalence and clinical findings of DWS. Because no case of severe dengue was observed, our main outcome was DWS, a clinical classification of dengue fever indicating potential severity. Predictive factors of DWS including thrombocytopenia (150,000/mm3), elevated hematocrit, hypoalbuminemia (<3.5 g/L), elevated transaminases (SGOT ≥120 IU/L, SGPT ≥80 IU/L) [21, 22] were analyzed using multivariable logistic regression analyses were employed to assess factors associated with DWS. These factors were selected a priori based on the literature [21, 22]. Abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, clinical fluid accumulation, mucosal bleeding, lethargy, hepatomegaly, rising hematocrit with concurrent thrombocytopenia, and AST/ALT levels ≥400 IU/L were not included in the analysis, as these features are part of the diagnostic criteria for DWS. We first analyzed the association of each potential predictive factors with the outcome (model 1, univariable analysis). The model 2 investigated the association of potential predictive factors with DWS. Subsequently, adjustments model (model 3) was made for age (≤5 years and >5 years), time from onset of fever to admission (<4 days and ≥4 days), gender, nutrition status (normal, low weight, overweight and obesity) and petechiae. The nutrition status was classified as WHO criteria [23]. The results were presented as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI).

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were derived from a 2 x 2 contingency table obtained by applying a predicted-probability cut-off to the fitted values of the multivariable model. The receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curve was generated by plotting sensitivity against 1-specificity across the full range of predicted probabilities, and the area under this curve (AUC) was estimated with the non-parametric DeLong method, providing its 95 % confidence interval. The optimal cut-off was defined by the Youden index (J = sensitivity + specificity – 1); the threshold that maximized J was selected and then used to report the final sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV. Model performance metrics are reported only for the DWS endpoint and are not compared with models predicting different outcomes.

RESULTS

Characteristics of studied population

A total of 332 children hospitalized for dengue infection were included in our analysis. The median age was 14 months (IQR: 8-41.5 months). Males accounted for 63.0% of the patients. Only two children had a prior history of dengue infection. Chronic conditions were present in 6.9% of the patients. The majority of children had normal weight (75.3%), while 6.0% were underweight, 9.9% were overweight, and 8.7% were obese. No child in our study had received dengue vaccine prior to hospitalization.

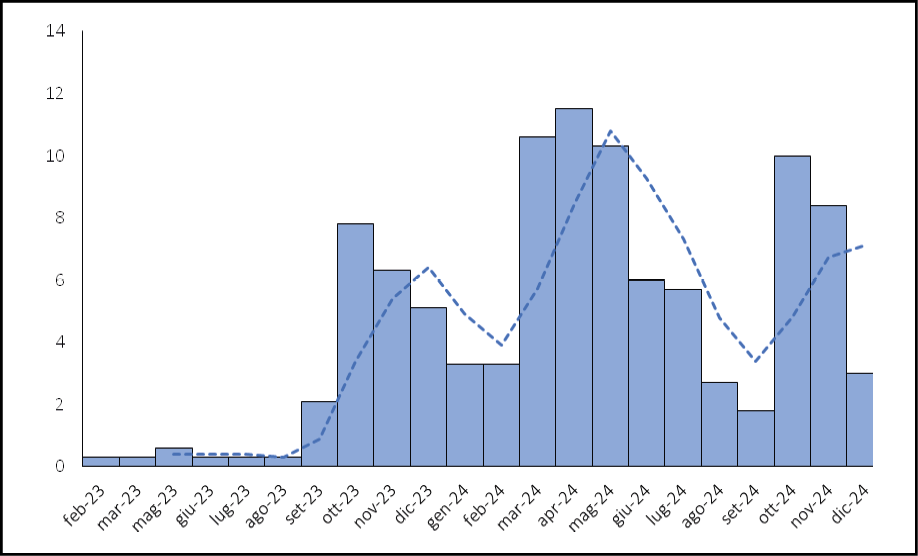

During the two-year study period, dengue hospitalizations were observed in most months, but the number of cases was generally low and irregular outside of the three distinct epidemic peaks: October to December 2023, March to July 2024, and October to December 2024 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Distribution of hospitalization time of children with Dengue fever.

Characteristics of patients with dengue with warning signs

According to the 2009 WHO classification, 50 patients (15.1%) were classified as DWS, while the remaining 282 patients (84.9%) had dengue without warning signs at hospital discharge. None of the children was classified as severe dengue. The median time from symptom onset to diagnosis of DWS was 3 days, (IQR: 2-3 days).

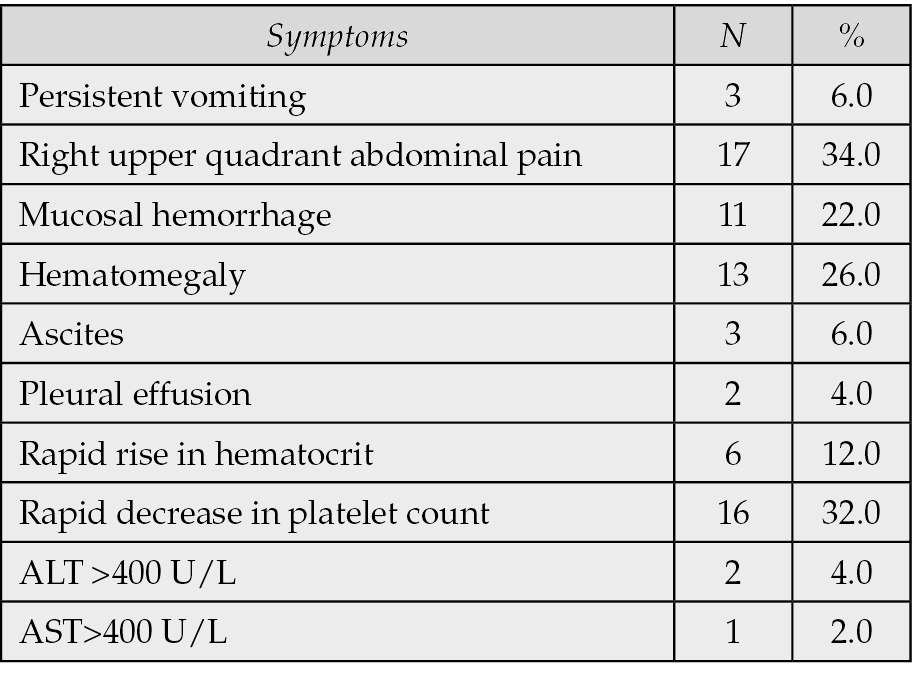

The distribution of warning signs is shown in Table 1. The most common clinical manifestations were right upper quadrant abdominal pain (34.0%), rapid decrease in platelet count (32.0%), and hepatomegaly (26.0%).

Table 1 - Distribution of warning signs among children with dengue fever.

Outcome of the pediatric patients with dengue fever

Most of all patients (309/332, 93.1%) recovered and were discharged; 23 (6.9%) patients were discharged at the request of their families. No patients required treatment in the intensive care unit, and no patients died. The median length of stay was 7 days, (IQR: 5-9 days), min = 1, max = 19 days.

Predictor factors of dengue with warning signs

In exploratory analyses, we assessed whether admission clinical and laboratory parameters were associated with later classification as DWS at discharge. The predictor factors of dengue with warning signs were analyzed on 50 patients with DWS and 282 without warning signs.

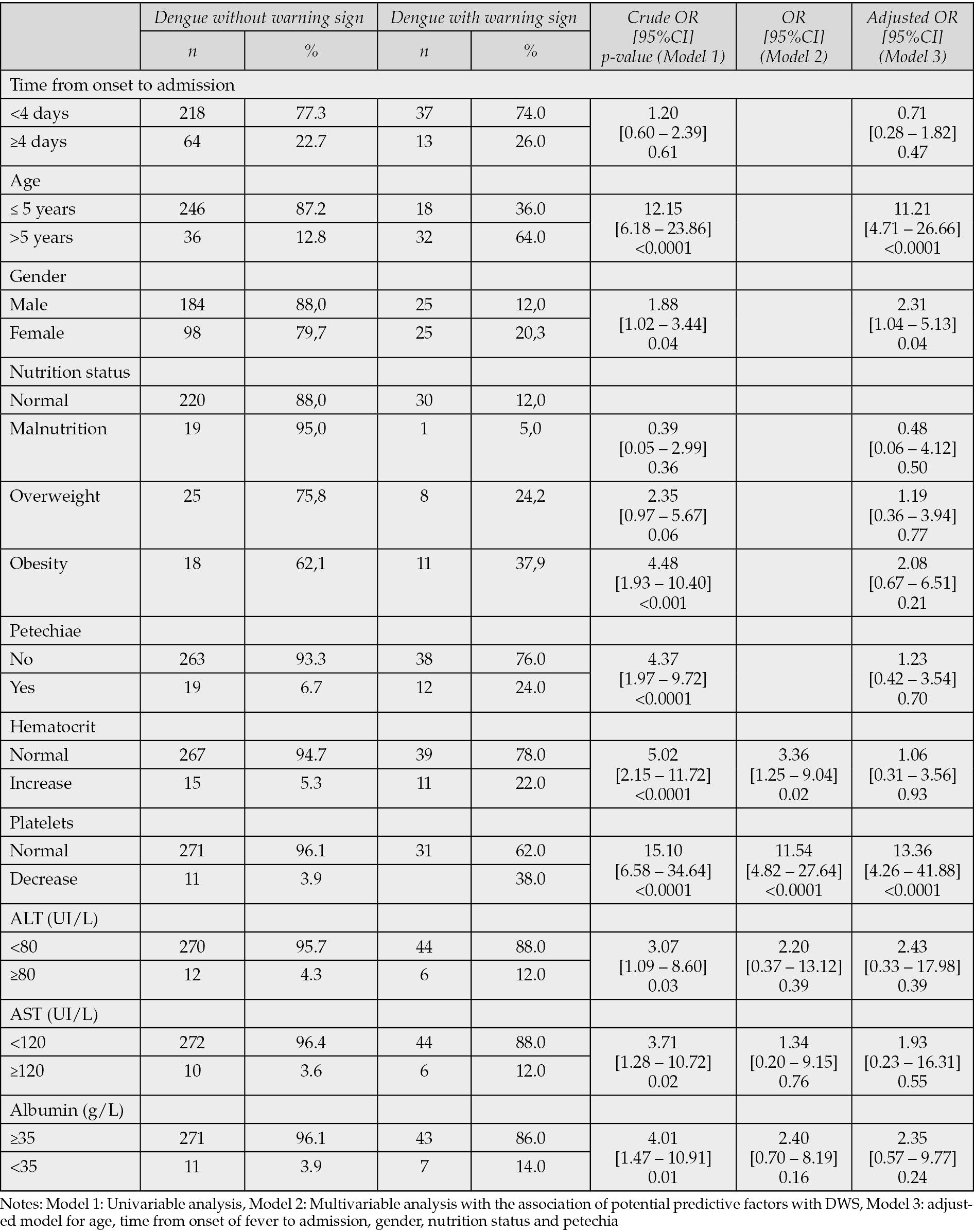

In model 1 (univariable analysis), thrombocytopenia, age >5 years, female sex, overweight/obesity, the presence of petechiae, increased hematocrit, low albumin, and elevated transaminases were associated with higher odds of DWS. In model 2 (multivariable analysis), thrombocytopenia and increased hematocrit remained significantly associated with DWS (Table 2).

Table 2 - Predictor factors of dengue with warning sign.

In the final adjusted model (model 3), thrombocytopenia at admission was independent predictor (OR = 13.36, 95%CI [4.26–41.88], p-value <0.0001). Children older than five years and female patients also had higher odds of DWS (OR=11.21, 95%CI [4.71–26.66], p-value <0.0001 and OR=2.32, 95%CI [1.05–5.13], p-value=0.04, respectively). Elevated hematocrit, hypoalbuminemia, elevated transaminases, abnormal nutritional status, petechiae and presentation ≥ 4 days from symptom onset were not associated with DWS after adjustment (Table 2).

Using the Youden method, an optimal predicted-probability threshold of 0.277 was identified. At this cut-off the model achieved a sensitivity of 74.0% and a specificity of 92.0%, corresponding to an area under the receiver-operating-characteristic curve of 0.83, giving an overall accuracy of 89.5%.

DISCUSSION

Although DWS is a WHO-defined clinical category, in practice these signs may not always be evident at admission, especially in younger children or in settings with limited diagnostic capacity. Our study therefore aims to identify simple laboratory parameters available at admission that could predict subsequent DWS. The findings support earlier risk stratification and timely clinical management. Our study does not propose a new clinical scoring system, is not intended to replace the WHO 2009 classification. Instead, the analyses were exploratory, seeking to identify whether simple, routinely available admission parameters could help anticipate which children may later meet DWS criteria during hospitalization. In particular, thrombocytopenia at admission emerged as a strong and consistent predictor, suggesting its potential utility as an early warning signal in resource-constrained settings where systematic assessment of WHO warning signs may be challenging. These findings are hypothesis-generating and require confirmation in larger, prospective studies.

We found that 15% of children met the WHO-2009 warning sign criteria, and no case progressed to severe dengue. Several contextual factors may explain these proportions. First, our hospital serves a predominantly rural catchment area with scattered households and consistently low Aedes mosquito indices throughout most of the year. Indeed, a prior study in South India reported a warning sign rate of 45.4% among children residing in densely populated areas with year-round vector presence [24]. High household mosquito densities and a greater likelihood of secondary dengue infections in urban settings amplify endothelial activation and plasma leakage, thereby increasing the frequency of warning signs. Conversely, a lower rate of 16% observed in in a tertiary care setting, where patients were promptly admitted and managed. Another potential reason is that early hospitalization allowed for timely interventions, such as fluid therapy and monitoring for warning signs, which are critical in preventing progression to severe dengue. Previous study also suggests that prompt referral to well-equipped health facilities plays a significant role in reducing severe outcomes [25].

The absence of severe dengue cases in our cohort mirrors reports from peri-rural areas, where early detection and efficient referral systems have mitigated disease progression. In our study, children were hospitalized a median of three days after fever onset, prior to the critical phase, allowing timely intervention with fluid therapy and close monitoring. In contrast, studies from India showed that the mean tenure of hospitalization was 3.8 days, increasing to 5.8 days in cohorts with severe dengue [26]. Vector control measures such as indoor daytime insecticide spraying and larval source reduction in schools, may also have contributed to lower mosquito density and viral inoculum, both of which have been linked to reduced severity in Vietnam.

In addition, dengue virus serotype plays an important role in disease severity. Northern Vietnam is predominantly affected by DENV-1, whereas areas with higher rates of severe dengue often experience serotype switching or lineage replacement, enhancing antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) in children previously infected with a different serotype [27]. Infection with DENV-1 alone elicits a milder cytokine response, contributing to a lower risk of severe progression [28]. A history of prior dengue infection is a known risk factor for severe disease [29]. However, such cases were rare in our cohort, with only two patients reporting previous dengue episodes.

Thrombocytopenia is an easily measurable indicator that reflects multiple pathogenic mechanisms of dengue. The virus suppresses platelet production and promotes immune-mediated destruction via NS1-induced autoantibodies and complement activation, leading to endothelial injury and increased plasma leakage. In a study of Vietnamese children, a platelet count below 100,000/mm3 on illness day 3 increased the risk of dengue shock six-fold, with a median warning lead time of 36 hours [14]. Furthermore, a daily drop in platelet count exceeding 20% was associated with a twofold increase in shock risk among children with dengue [14]. Our findings replicate this pattern, suggesting that thrombocytopenia is a reliable prognostic marker of disease severity. Thrombocytopenia has also been incorporated into clinical scoring systems in India and Southeast Asia for predicting severe dengue [30, 31].

Our study did not assess the temporal trajectory of platelet decline. Nevertheless, monitoring strategies must be adapted to available resources and contextual constraints. Frequent blood sampling in pediatric patients is challenging for healthcare staff and often elicits resistance from caregivers. We therefore propose a pragmatic schedule whereby platelet counts are measured on illness day 4 (or at admission if later), and repeated only if the platelet count is <150,000/mm³ or if clinical signs worsen. This targeted approach minimizes reagent use and patient discomfort while maintaining diagnostic accuracy during peak epidemic periods.

The association between age and dengue severity remains inconsistent across studies. Some research has reported greater severity in younger children due to physiological plasma leakage, whereas our study and others have observed higher risk among school-aged children, consistent with secondary heterotypic immune responses [32, 33]. The predominance of female cases has been less commonly reported, though evidence from original data and meta-analysis have noted similar trends [33, 34]. These differences may be attributed to healthcare-seeking behaviors or hormonal influences on immune response, though the underlying mechanisms remain unclear [34].

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective single-center design and reliance on medical records may result in incomplete data and misclassification of warning signs. Although our sample included 332 pediatric patients, it remains relatively small, warranting larger multicenter cohort studies to improve effect estimation and to comprehensively assess prognostic factors for severe dengue in children. Additionally, we did not perform serotype identification via PCR, which may influence disease severity across epidemic waves in the region [33, 35]. Several prognostic tools in children predict severe dengue or critical admission. Because these target different endpoints than DWS, direct area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) comparisons are not appropriate. Our model is specific to DWS, we therefore report discrimination and operating characteristics for this outcome only, and emphasize the need for external validation. Finally, our cohort primarily comprised children from low-density rural areas, caution is therefore advised when generalizing findings to urban settings with higher Aedes indices, fluctuating serotype dynamics, or reduced access to care. External validation in diverse epidemiological contexts is essential before widespread implementation.

CONCLUSIONS

Our exploratory analyses suggest that age >5 years, female sex, and thrombocytopenia at admission as independent predictors of DWS in children, yielding an AUROC of 0.83 using only routinely available data at primary care level. The moderate prevalence of warning signs and the absence of severe dengue in our cohort likely reflect early hospitalization and a low proportion of secondary infections. The model’s reliance on basic clinical and laboratory information, without the need for complex diagnostics, makes it a practical tool for early risk stratification and resource allocation in settings with limited laboratory capacity. It is particularly suited to primary health facilities in low- and middle-income countries such as Vietnam, where timely referral is essential.

Conflict of interest

The author declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: TLD, VTH; methodology: NQL, TLD, NTH, VTH; software: TLD, VTH; validation: NQL, HAN, KHV, KLD, NTH, TLD, VTH; formal analysis: NQL, TLD, VTH; investigation: NQL, HAN, KHV, KLD, NTH, TLD, VTH; resources: TLD, VTH; data curation: NQL, HAN, KHV, KLD; writing - original draft: NQL, TLD, VTH; writing - review and editing: NQL, HAN, KHV, KLD, NTH, TLD, VTH; visualization: TLD, VTH; supervision: TLD, VTH; project administration: TLD, VTH

Ethics statement

The protocol was approved by Thai Binh University of Medicine and Pharmacy (approval date: 31 March 2025; reference number: 690, project code: SV.2025.15). The study was performed according to the good clinical practices recommended by the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. This was a retrospective study: informed consent was waived.

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author [V.T.H] upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our colleagues at Thai Binh Pediatric Hospital for their help in data collection.

REFERENCES

[1] Lim A, Shearer FM, Sewalk K, et al. The overlapping global distribution of dengue, chikungunya, Zika and yellow fever. Nat Commun. 2025; 16 (1): 3418. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-58609-5.

[2] Hadinegoro SRS. The revised WHO dengue case classification: does the system need to be modified? Paediatr Int Child Health. 2012; 32 Suppl 1: 33-38. https://doi.org/10.1179/2046904712Z.00000000052.

[3] Salazar Flórez JE, Marín Velasquez K, Segura Cardona ÁM, et al. Clinical Manifestations of Dengue in Children and Adults in a Hyperendemic Region of Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2024; 110: 971-978. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.23-0717.

[4] Zhou M, He Y, Wu L, Weng K. Trends and cross-country inequalities in dengue, 1990-2021. PLoS One. 2025; 20: e0316694. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0316694.

[5] Weerasinghe NP, Bodinayake CK, Wijayaratne WMDGB, et al. Direct and indirect costs for hospitalized patients with dengue in Southern Sri Lanka. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022; 22: 657. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08048-5.

[6] Sonali Fernando E, Headley TY, Tissera H, Wilder-Smith A, De Silva A, Tozan Y. Household and Hospitalization Costs of Pediatric Dengue Illness in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021; 105: 110-116. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-1179.

[7] Ricardo-Rivera SM, Aldana-Carrasco LM, Lozada-Martinez ID, et al. Mapping Dengue in children in a Colombian Caribbean Region: clinical and epidemiological analysis of more than 3500 cases. Infez Med. 2022; 30: 602-609. https://doi.org/10.53854/liim-3004-16.

[8] World Health Organization (WHO). Dengue guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control : new edition. World Health Organization; 2009. Available at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44188 [accessed July 20, 2025]

[9] Bodinayake CK, Tillekeratne LG, Nagahawatte A, et al. Evaluation of the WHO 2009 classification for diagnosis of acute dengue in a large cohort of adults and children in Sri Lanka during a dengue-1 epidemic. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018; 12: e0006258. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006258.

[10] Alam R, Fathema K, Yasmin A, Roy U, Hossen K, Rukunuzzaman M. Prediction of severity of dengue infection in children based on hepatic involvement. JGH Open. 2024; 8: e13049. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgh3.13049.

[11] Khan MAS, Al Mosabbir A, Raheem E, et al. Clinical spectrum and predictors of severity of dengue among children in 2019 outbreak: a multicenter hospital-based study in Bangladesh. BMC Pediatr. 2021; 21: 478. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02947-y.

[12] Vélez Jaramillo Y, Reveiz Montes MA, Galván-Barrios JP, Picón-Jaimes YA. Maternal and foetal outcomes in women with gestational Dengue: A systematic review. Infez Med. 2025; 33: 15-28. https://doi.org/10.53854/liim-3301-3.

[13] Trieu HT, Vuong NL, Hung NT, et al. The influence of fluid resuscitation strategy on outcomes from dengue shock syndrome: a review of the management of 691 children in 7 Southeast Asian hospitals. BMJ Glob Health. 2025; 10: e017538. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2024-017538.

[14] Lam PK, Ngoc TV, Thu Thuy TT, et al. The value of daily platelet counts for predicting dengue shock syndrome: Results from a prospective observational study of 2301 Vietnamese children with dengue. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017; 11: e0005498. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005498.

[15] Vo LT, Do VC, Trinh TH, Nguyen TT. In-Hospital Mortality in Mechanically Ventilated Children With Severe Dengue Fever: Explanatory Factors in a Single-Center Retrospective Cohort From Vietnam, 2013-2022. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2025; 26: e796-805. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000003728.

[16] Vuong NL, Manh DH, Mai NT et al. Criteria of “persistent vomiting” in the WHO 2009 warning signs for dengue case classification. Trop Med Health. 2016; 44: 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-016-0014-9.

[17] Hoang LT, Lynn DJ, Henn M, et al. The early whole-blood transcriptional signature of dengue virus and features associated with progression to dengue shock syndrome in Vietnamese children and young adults. J Virol. 2010; 84: 12982-12994. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01224-10.

[18] Lam PK, Tam DTH, Dung NM, et al. A Prognostic Model for Development of Profound Shock among Children Presenting with Dengue Shock Syndrome. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0126134. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0126134.

[19] Mettananda C, Perera K, Nayeem N, et al. The role of serum ferritin in predicting plasma leakage among adults and children with dengue in Sri Lanka: a multicentre, prospective cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health - Southeast Asia. 2025; 37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2025.100606.

[20] Vietnam Ministry of Health. Decision 2760/QD-BYT 2023 Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of Dengue hemorrhagic fever [in Vietnamese]. Available at: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/ The-thao-Y-te/Quyet-dinh-2760-QD-BYT-2023-Huong-dan-chan-doan-dieu-tri-So-xuat-huyet-Dengue-572227.aspx [accessed August 28, 2025].

[21] Nguyen RN, Lam HT, Phan HV. Liver Impairment and Elevated Aminotransferase Levels Predict Severe Dengue in Vietnamese Children. Cureus. 2023; 15: e47606. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.47606.

[22] Huy BV, Toàn NV. Prognostic indicators associated with progresses of severe dengue. PLoS One. 2022; 17: e0262096. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262096.

[23] World Health Organization. Growth reference data for 5-19 years n.d. Available at: https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years [accessed July 8, 2025].

[24] Naaraayan SA, Sundar KC. Risk factors of severe dengue in children: A nested case-control study. J Ped Crit Care. 2021; 8: 224. https://doi.org/10.4103/jpcc.jpcc_59_21.

[25] Nusrat N, Chowdhury K, Sinha S, Mehta M, Kumar S, Haque M. Clinical and Laboratory Features and Treatment Outcomes of Dengue Fever in Pediatric Cases. Cureus. 2024; 16: e75840. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.75840.

[26] Mishra S, Ramanathan R, Agarwalla SK. Clinical Profile of Dengue Fever in Children: A Study from Southern Odisha, India. Scientifica (Cairo). 2016; 2016: 6391594. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6391594.

[27] Dang TT, Pham MH, Bui HV, Van Le D. Whole genome sequencing and genetic variations in several dengue virus type 1 strains from unusual dengue epidemic of 2017 in Vietnam. Virol J. 2020; 17: 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-020-1280-z.

[28] Ho T-S, Wang S-M, Lin Y-S, Liu C-C. Clinical and laboratory predictive markers for acute dengue infection. J Biomed Sci. 2013; 20: 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/1423-0127-20-75.

[29] Macchia A, Figar S, Biscayart C, González Bernaldo de Quirós F. Impact of prior dengue infection on severity and outcomes: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2024; 48: e129. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2024.129.

[30] Rao AS, Pai BHK, Adithi K, et al. Scoring model for exploring factors influencing mortality in dengue patients at a tertiary care hospital: a retrospective study. Discov Appl Sci. 2024; 6: 671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-024-06302-5.

[31] Srisuphanunt M, Puttaruk P, Kooltheat N, Katzenmeier G, Wilairatana P. Prognostic Indicators for the Early Prediction of Severe Dengue Infection: A Retrospective Study in a University Hospital in Thailand. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022; 7: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7080162.

[32] Ferreira RAX, Kubelka CF, Velarde LGC, et al. Predictive factors of dengue severity in hospitalized children and adolescents in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2018; 51: 753-760. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0036-2018.

[33] Hernández Bautista PF, Cabrera Gaytán DA, Santacruz Tinoco CE, et al. Retrospective Analysis of Severe Dengue by Dengue Virus Serotypes in a Population with Social Security, Mexico 2023. Viruses. 2024; 16: 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16050769.

[34] Sangkaew S, Ming D, Boonyasiri A, et al. Risk predictors of progression to severe disease during the febrile phase of dengue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infect Dis. 2021; 21: 1014-1026. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30601-0.

[35] Soo KM, Khalid B, Ching SM, Chee HY. Meta-Analysis of Dengue Severity during Infection by Different Dengue Virus Serotypes in Primary and Secondary Infections. PLoS One. 2016; 11: e0154760. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154760.