Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 4, 391-403, 2025

doi: 10.53854/liim-3304-4

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Administration of antivirals, IL-6 inhibitors, monoclonal neutralizing antibodies and systemic corticosteroids in acute SARS-CoV-2 infection do not reduce the subsequent burden of Long-COVID symptoms

Marco Floridia1, Liliana Elena Weimer1, Aldo Lo Forte2, Paolo Palange3, Maria Rosa Ciardi3, Patrizia Rovere-Querini4, Piergiuseppe Agostoni5,6, Emanuela Barisione7, Silvia Zucco8, Paola Andreozzi9, Paolo Bonfanti10,11, Stefano Figliozzi12,13, Matteo Tosato14, Donato Lacedonia15, Kwelusukila Loso16, Paola Gnerre17, Maria Antonietta di Rosolini18, Domenico Maurizio Toraldo19, Giuseppe Pio Martino20, Guido Vagheggini21,22, Gianfranco Parati23,24, Graziano Onder14, and the ISS Long-COVID Study Group.

1 National Center for Global Health, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy;

2 Department of Multidimensional Medicine, Internal Medicine Unit, San Giovanni di Dio Hospital, Florence, Italy;

3 Department of Public Health and Infectious Diseases, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy;

4 IRCCS Ospedale S. Raffaele and Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan, Italy;

5 Centro Cardiologico Monzino, IRCCS, Milan, Italy;

6 Department of Clinical Science and Community Medicine, University of Milan, Milan, Italy;

7 IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genova, Italy;

8 Infectious Diseases Unit, Ospedale Amedeo di Savoia, Turin, Italy;

9 Predictive Medicine Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, Endocrine-Metabolic Sciences and Infectious Diseases, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Policlinico Umberto I, Rome, Italy;

10 Infectious Diseases Unit, Fondazione IRCCS San Gerardo dei Tintori, Monza, Italy;

11 University of Milano-Bicocca, School of Medicine and Surgery, Monza, Italy;

12 IRCCS Humanitas Research Hospital, Rozzano, Milan, Italy;

13 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Humanitas University, Pieve Emanuele (MI), Italy.;

14 Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy;

15 Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Foggia, Foggia, Italy;

16 Infectious Diseases and Hepatology Unit, Manduria Hospital, Taranto, Italy;

17 Internal Medicine Department, ASL 2 Savonese, Savona, Italy;

18 UOC Malattie Infettive, ASP Ragusa, Ragusa, Italy;

19 Respiratory Care Unit, Rehabilitation Department, “V. Fazzi” Hospital, Azienda Sanitaria Locale, San Cesario, Lecce, Italy;

20 Internal Medicine Unit, Hospital Augusto Murri, Fermo, Italy;

21 Department of Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties, Respiratory Failure Pathway, Azienda USL Toscana Nordovest, Pisa, Italy;

22 Fondazione Volterra Ricerche ONLUS, Volterra (Pisa), Italy;

23 Department of Clinical Sciences and Community Medicine, University of Milan, Milan, Italy;

24IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milan, Italy.

Article received 21 July 2025 and accepted 30 September 2025

Corresponding author

Marco Floridia

E-mail: marco.floridia@iss.it

SUMMARY

Purpose: Some studies have suggested that therapeutic interventions able to mitigate the acute phase of COVID-19 can also reduce the risk of Long-COVID and its severity, but the issue is still controversial.

Methods: We examined in a national cohort of patients followed in Long-COVID centers the risk of persistent symptoms according to administration in acute COVID-19 of four drug classes: antivirals, IL-6 inhibitors, monoclonal neutralizing antibodies and systemic corticosteroids. Final risk estimates for 26 symptoms were expressed as adjusted odds ratios calculated in multivariable logistic regression models that included as covariates demographics, comorbidities, BMI, smoking, severity of acute disease, hospitalization, level of respiratory support, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and treatments administered during acute infection.

Results: The final population included 1534 adult patients (mean age 60.3 years, 67.0% hospitalised during acute COVID-19). Treatments administered during acute phase included systemic steroids (52.8%), antivirals (20.7%, mostly remdesivir), IL-6 inhibitors (9.4%) and neutralizing antibodies (3.9%). After a mean interval of 338 days from acute COVID-19, 1181 patients (77.0%) presented persisting symptoms. For the drug classes considered, some protective associations were found in univariate analyses, that were however not maintained adjusting for confounders in multivariate analyses. Systemic corticosteroids and IL-6 inhibitors showed some negative associations with isolated symptoms.

Conclusions: Some drug classes showed a protective effect that was however not confirmed in multivariable analyses, underlining the importance of adjusting for a comprehensive number of covariates. Clinicians should consider the possibility that systemic corticosteroids and IL-6 inhibitors administered during acute COVID-19 may prolong the persistence of particular symptoms.

Keywords: COVID-19; Long-COVID; symptoms; antivirals, IL-6 inhibitors; monoclonal neutralizing antibodies.

INTRODUCTION

The long-term sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, commonly denominated as Long-COVID (LC) or Post-Covid conditions (PCC), have been recognized as a distinct clinical entity characterized by a wide array of possible manifestations [1-7]. Although a precise estimate of its prevalence is difficult, due to a remarkable heterogeneity in the definition of the condition and in the design of published studies, the chronic burden of disease is huge, with several millions of individuals suffering worldwide from persisting and often disabling chronic symptoms [8-10]. The substantial uncertainty about the mechanisms that lead to this prolonged disease and the absence of specific diagnostic biomarkers pose important challenges to an effective treatment of this condition. The observed correlation between severity of acute disease and risk of persisting symptoms has suggested that therapeutic interventions able to mitigate the acute phase of the disease can also reduce the risk of developing Long-COVID and its severity [11, 12]. In this context, the effect of antiviral treatment administered during the acute phase of the disease has been evaluated in retrospective clinical cohort studies and in population studies based on large health databases, but the findings obtained are heterogenous and often inconsistent [12-27]. The above discrepancies may be explained by differences in several features, including design, treatment differences in setting, doses, administration route and duration, definition of control groups, follow up observation time, phase of the pandemic and viral variants involved, outcomes used (symptoms or clinical events), population characteristics (demographics, settings, severity of acute disease and risk factors), source of data (clinical records, surveys, administrative databases), and by the number and type of the confounding variables considered. Overall, further investigation based on a comprehensive number of cofactors may be relevant to better define the role of antiviral and immunomodulating treatments administered during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection in preventing or mitigating long-term sequelae. With the aim to contribute to this issue, we used data from a multicentre national study of patients accessing care for Long-COVID in specialized centers, assessing the possible impact of antivirals, interleukin-6 (IL-6) inhibitors, monoclonal neutralizing antibodies and systemic steroids, administered during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, on the long-term persistence of different symptoms, considering a wide number of covariates in order to provide adjusted risk estimates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study overview and population

The present study is part of the project “Analysis and strategies for responding to the long-term effects of the COVID-19 infection (Long-COVID)”, funded by the Italian Ministry of Health. The clinical study, structured as an observational cohort, started in January 2023 and was closed in March 2024, with data extracted on April 2, 2024. The assessment of symptoms had a mixed retrospective/prospective design. Symptom collection was retrospective, based on clinical records and patient interview, for patients who had two previous visits before the start of the study (January 2023), and prospective for patients with one or two visits after this date. Data on demographics, acute infection and comorbidities were taken from clinical records. Study data were entered by medical staff at the participating centers using an online dedicated platform. Study participation was voluntary and all patients provided written informed consent. Inclusion criteria for the present analysis were age at least 18, a recorded date of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection (defined by date of first positive swab), a clinical visit for symptom assessment performed at least 12 weeks after acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, and available information on administration of four classes of medications during acute SARS-CoV-2 disease (antivirals, IL-6 inhibitors, monoclonal anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and oral or intravenous steroids). Patients who received convalescent plasma were excluded.

Data collection

For data collection, a shortened version of the Post COVID-19 Case Report Form from the WHO Global Clinical Platform for COVID-19 was used, that included patient demographics, comorbidities, severity and timing of acute COVID, plus 30 different symptoms (fatigue, dyspnea, sleep disturbances, memory loss, joint pain or swelling, muscle pain, difficult concentration, cough, anxiety, taste reduction, smell reduction, palpitations/tachycardia, depressed mood, skin disorders/alopecia, thoracic pain, paresthesia, brain fog, headache, disorders of equilibrium or gait, visual disturbances, weight loss, diarrhea, hearing disturbances, pharygodynia, loss of appetite, nausea or vomiting, fever, menstrual disorders, chilblains, delirium or hallucinations) [28]. Four classes of medications administered during acute SARS-CoV-2 disease were considered:

1) antivirals;

2) systemic (oral or intravenous) steroids;

3) IL-6 inhibitors;

4) monoclonal anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

Treatment administration followed the indications of Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA). Antivirals approved by AIFA for use in COVID-19 during the study were remdesivir, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir and molnupiravir [29]. The approved IL-6 inhibitors were tocilizumab (first choice) and sarilumab (second choice), and the approved anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies were casirivimab-imdevimab, regdanvimab, sotrovimab and tixagevimab-cilgavimab [30, 31]. Information on the individual drugs used was available for antivirals only (remdesivir, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, molnupiravir).

Definitions

Severity of acute SARS-CoV-2 disease was defined as mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2), severe (grade 3) or critical (grade 4) according to the WHO grading [28]. Respiratory assistance was categorized as none, low or high flow inhaled oxygen, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), mechanical ventilation (MV) and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Phase of the pandemic was categorised as Pre-Omicron or Omicron according to occurrence of date of acute infection before or after December 23, 2021 [32]. The comorbidities considered were neoplastic disease, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, renal failure, stroke, anxiety or depressive disorders, chronic liver disease, respiratory failure, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, autoimmune diseases, asthma, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), plus a general category of other major conditions, reviewed by two of the authors. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination status was categorized in three groups according to timing of first dose administration (before SARS-CoV-2 infection, after SARS-CoV-2 infection, not vaccinated).

Data analysis

Data were summarized as proportions for categorical variables and as means with standard deviations for quantitative variables. Mean values were compared by Student’s T test and proportions by the chi-square test in contingency tables, calculating unadjusted odds ratios (UOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Univariate analyses evaluated the association of individual persisting symptoms with each of the four drug classes considered (antivirals, systemic steroids, neutralizing antibodies and IL-6 inhibitors) and with sex, age, body mass index, smoking, individual and cumulative comorbidities, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, phase of the pandemic, hospitalisation and admission to intensive care unit, WHO severity grade, level of respiratory assistance and time from acute infection to symptom evaluation. For the symptoms reported by at least 20 individuals such associations were further explored in multivariable logistic regression models, calculating for the four drug classes the adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95%CI for persistence of individual symptoms. The models included all the variables associated in univariate analyses with persistence of individual symptoms at a significance level <0.15 (p value) plus age and sex. The goodness of fit of the models was tested with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and tests of collinearity. No input was used to substitute missing data. All analyses were performed using the SPSS software, version 29.0 (IBM Corp, 2017, Armonk, NY, US).

RESULTS

Population

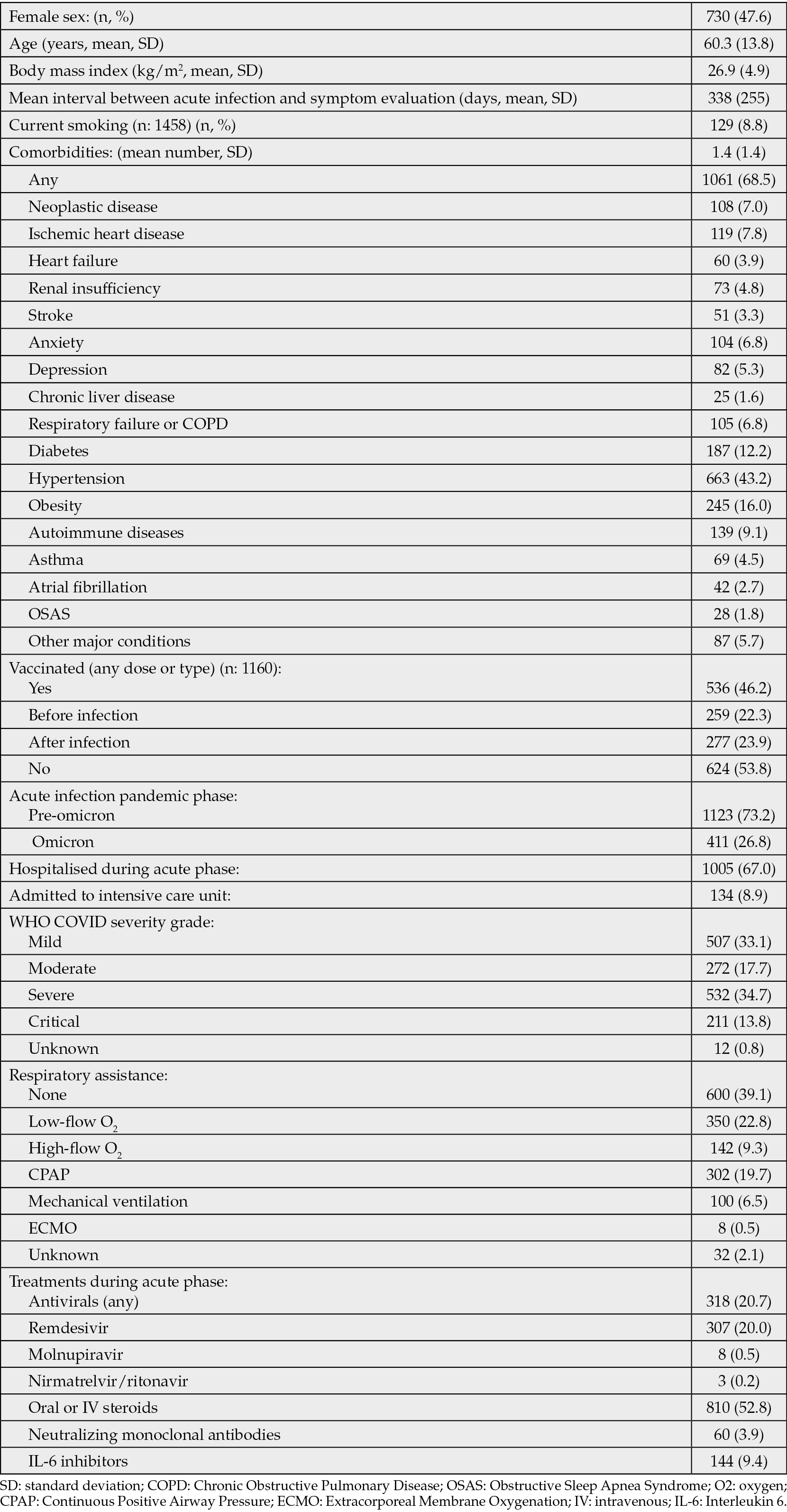

At study closure, data for 1910 patients from 30 clinical centers were entered in the platform. According to the eligibility criteria, the following patients were excluded: age below 18 (n: 106), visited before 12 weeks from acute infection (n: 103), use of convalescent plasma (n: 4), missing information on date of COVID-19, date of visit or presence of symptoms (n: 63), missing information on the considered treatments in acute phase (n: 100), for a final sample of 1534 patients aged 18 or more, clinically evaluated at least 12 weeks after acute infection. The general characteristics of the study population are reported in Table 1. Overall, the individuals enrolled were characterised by relatively advanced age (mean: 60.3 years), common presence of comorbidities (68.5%) and frequent occurrence of hospitalisation during acute COVID-19 (67.0%); roughly half of them had presented severe or critical acute SARS-CoV-2 infection and more than one quarter received CPAP, mechanical ventilation or ECMO as respiratory support. Treatments administered during acute phase included systemic steroids in 52.8% of the cases, antivirals (mostly remdesivir) in 20.7%, and less frequent use of IL-6 inhibitors (9.4%) or neutralizing antibodies (3.9%).

Table 1 - Population characteristics.

Symptom evaluation

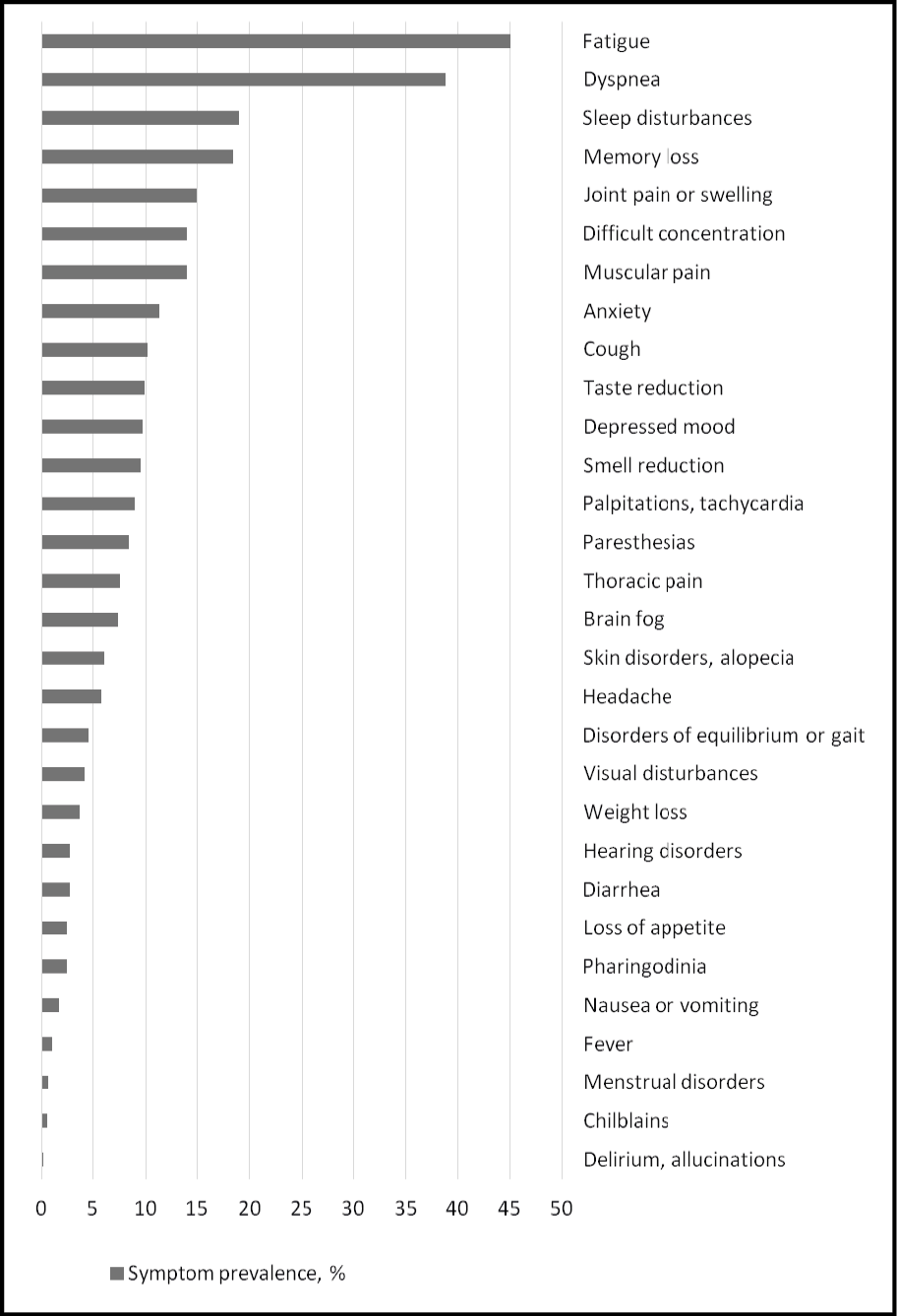

The mean interval between acute SARS-CoV-2 infection and symptom evaluation was of 338 days (SD 255). At this clinical assessment, 1181 patients (77.0%) presented at least one persisting symptom (mean number of symptoms: 3.7, SD 2.9). The distribution of symptoms is presented in Figure 1. Fatigue (45.0%) and dyspnea (38.8%) were the predominant symptoms observed, followed by sleep or memory disturbances (19.0% and 18.4%, respectively), articular or muscular pain (15.0% and 13.9%, respectively), difficult concentration (14.0%), anxiety (11.3%), taste or smell abnormalities (9.9% and 9.4%, respectively), depressed mood (9.7%), palpitation/tachycardia (9.0%), paresthesia (8.4%), thoracic pain (7.6%), brain fog (7.4%), skin disorders or alopecia (6.1%) and headache (5.8). Other symptoms were less common, affecting less than 5% of the individuals (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Prevalence of individual symptoms at clinical assessment.

Associations between treatments and symptoms

in univariate analyses.

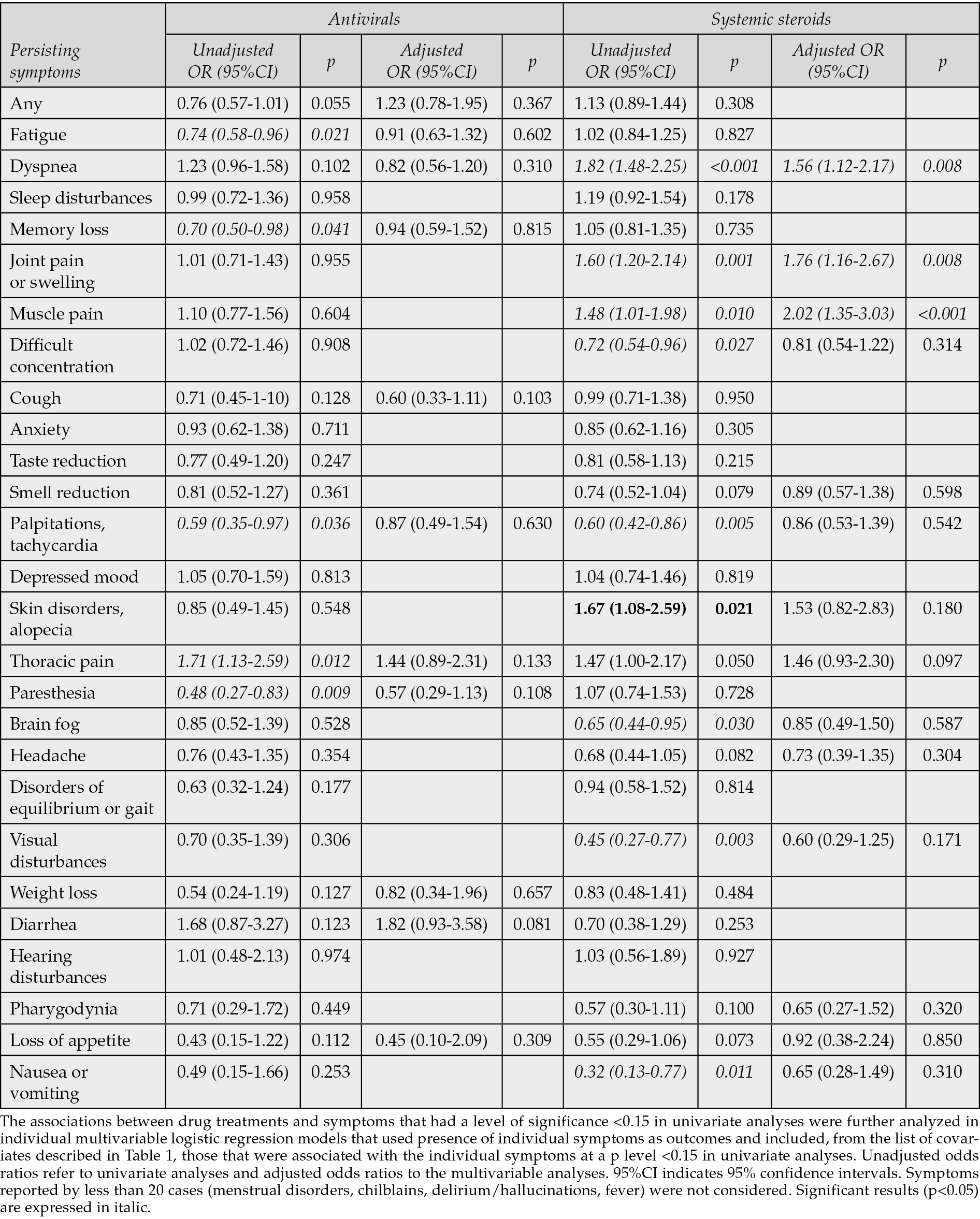

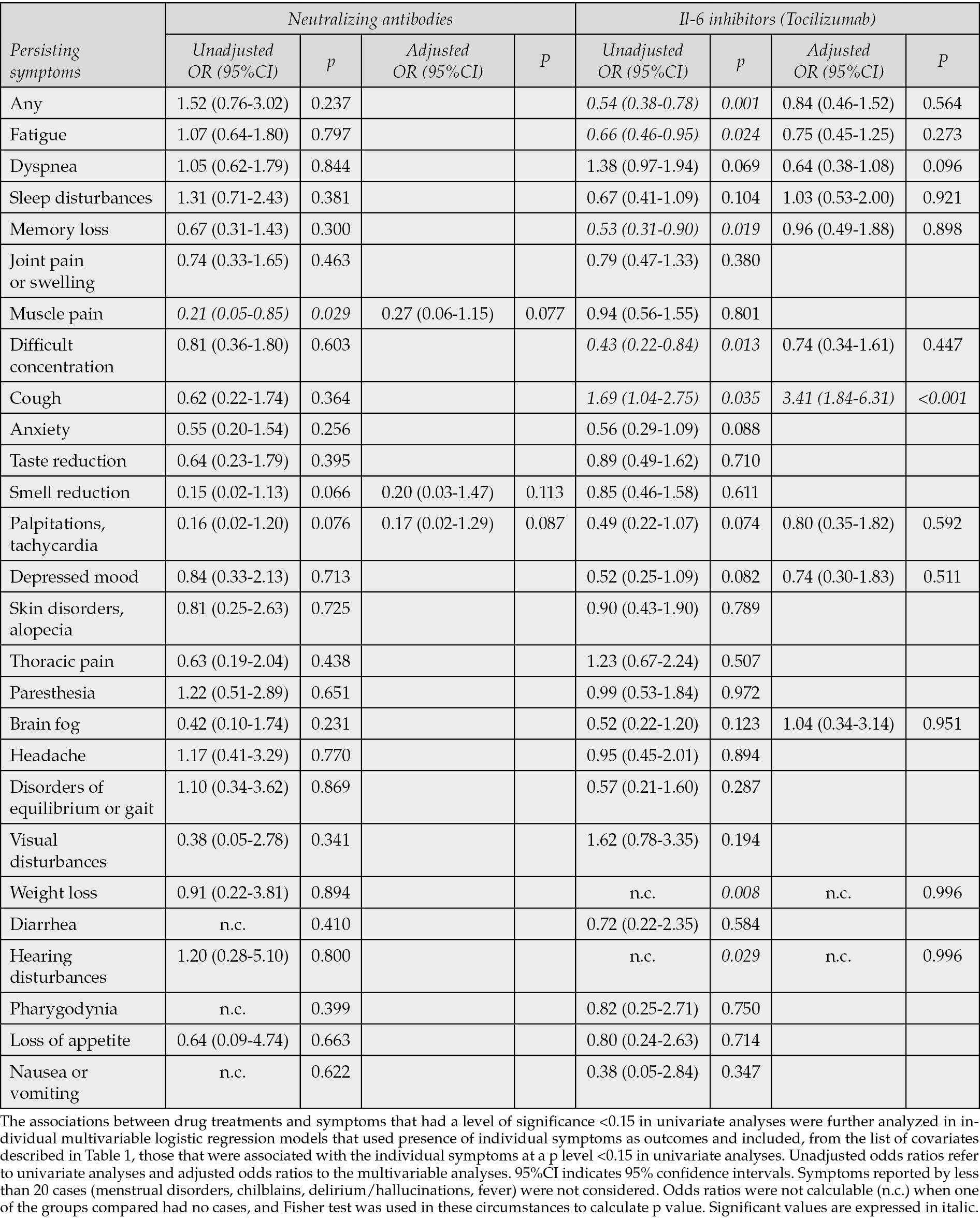

The associations between the treatments administered during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection and presence of persisting symptoms were first evaluated in contingency tables and presented as unadjusted odds ratios. Use of antivirals was associated to a significant reduced risk of fatigue, palpitations/tachycardia, and paresthesia, and to an increased risk of thoracic pain. Use of systemic steroids was associated to a reduced risk of difficult concentration, palpitations/tachycardia, visual disturbances, brain fog, nausea/vomiting, and to an increased risk of dyspnea, articular pain or swelling, muscular pain, and skin disorders. Use of neutralizing antibodies was associated to a reduced risk of muscle pain; use of tocilizumab was associated to a reduced risk of any symptom, fatigue, memory loss, difficult concentration, weight loss, hearing disturbances, and to an increased risk of cough (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2 - Associations (unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios) of persisting symptoms with antivirals and systemic steroids administered during acute COVID-19.

Table 3 - Associations (unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios) of persisting symptoms with neutralizing antibodies and tocilizumab administered during acute COVID-19.

Associations between treatments and symptoms in multivariable analyses

The multivariable models that reassessed the possible associations (p<0.15) found in univariate analyses between the four drug classes and persistence of individual symptoms were conducted on an average number of 1154 cases (75.2%), and adjusted for an average of 13 covariates, individually included in each model. The results showed that none of the potentially protective effects shown for the four drug categories in univariate analyses were confirmed. Use of IL-6 inhibitors in acute COVID-19 was associated with an increased risk of cough (AOR 3.41, 95% CI 1.84-6.41, p<0.001), and use of steroids with increased risks of subsequent dyspnea (AOR 1.56, 95%CI 1.12-2.17, p=0.008), joint pain or swelling (AOR 1.76, 95%CI 1.16-2.67, p=0.008) and muscle pain (AOR 2.02, 95%CI 1.35-3.03, p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

Long-COVID is a relevant cause of morbidity, with no specific treatments beyond symptomatic relief. Disease severity has been reported as a possible risk factor for development of Long-COVID, and it has been postulated that therapeutic interventions that reduce the severity of acute COVID-19 may have a preventive effect on Long-COVID [11, 12, 33]. Antiviral drugs and anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies may act reducing viral multiplication and spread, and steroids and IL-6 inhibitors may mitigate acute inflammation and cytokine production. Our data suggested for these drugs some protective effect in univariate analyses, but after adjustment for relevant covariates none of the above drug categories were significantly effective in protecting against an array of 30 Long-COVID symptoms. These findings contribute to the controversial evidence on this issue, suggesting that covariate adjustment is a key element that may significantly influence the study results and conclusions.

Overall, there is no consistent evidence that administering antiviral or antinflammatory drugs during acute COVID-19 prevents occurrence of Long-COVID. Data on the effect of IL-6 inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies are scarce. For these two drug categories, our findings are consistent with those of other studies, that also found no protective effect of their administration during acute COVID-19, or showed only benefits for isolated symptoms (neurocomportamental symptoms in patients who received monoclonal antibodies) [12-14]. A greater number of studies have evaluated the potential protective effect of antivirals, but with a large heterogeneity in design, inclusion criteria, and, ultimately, in findings. In the short term, antivirals reduced the general risk of Long-COVID, and in a systematic review this drug category showed a general protective effect, reducing 8 out of 22 long COVID symptoms, but the number of included studies was low, and the benefits were apparent only for nirmatrelvir/r and molnupiravir, with no protective effect of remdesivir [12, 14]. In other studies, remdesivir reduced symptom duration and the risk of some specific symptoms, but adjustment included only a limited number of covariates [13, 18]. Other studies found no global benefit of remdesivir administration in acute COVID-19, with a possible protective effect only on respiratory symptoms [34] and stroke [15]. In one of the few randomized studies available, remdesivir administered in acute phase had no significant effect on symptoms at 3 months [22]. Administration of nirmatrelvir/r in acute COVID-19 produced no general protection on Long-COVID symptoms, partial protection on some symptoms (brain fog, thoracic pain), or only minor reductions in postacute symptom sequelae of COVID-19 [16, 17, 21]. In randomized studies of individuals with already established Long-COVID symptoms, nirmatrelvir did not improve symptoms and health status [35, 36]. Some retrospective studies based on large administrative databases evaluated the role of nirmatrelvir and/or molnupiravir using as outcomes clinical events instead of symptoms. Some found a reduced event occurrence [19, 25], but others found no general protective effect or only benefits for some specific conditions, represented by cardiovascular or respiratory events [20, 23, 24]. For systemic corticosteroids, the findings were also variable [12, 13, 37, 38]. In our study, their use during acute COVID-19 produced no general long-term protection but was instead associated with a possible increase in the risk of some specific symptoms (dyspnea, articular pain or swelling and muscle pain). This is consistent with other studies that showed an association between the use of systemic corticosteroids in acute COVID-19 and an increased risk of Long-COVID symptoms, dyspnea, and daily activity limitations [32, 33]. This potential risk increase could be due to the more common use of these drugs in patients with severe acute disease, which are also at higher risk of postacute sequelae, therefore representing a spurious association [12]. In the present study, risk estimates were adjusted for severity grade of acute disease, hospitalization, admission to ICU and level of respiratory support, making this possibility less likely. An alternative hypothesis for the findings is that corticosteroids may partially suppress the acute immune response to the virus, favouring virus spread and persistence in tissues and hence increasing the risk of Long-COVID manifestations [11, 12].

Use of IL-6 inhibitors in acute COVID-19 also showed a symptom-specific negative effect, represented by a 3-fold higher risk of subsequent persistent cough. Although we cannot exclude, despite the extensive adjustments, the risk of a spurious association, tocilizumab use in rheumatoid arthritis has been associated with an increased risk of respiratory infectious adverse events, and such reduced protection against respiratory infections could explain the negative association found [39]. A cough reflex impairment has also been postulated to explain chronic cough occurring in Long-COVID patients without pulmonary sequelae. Viral infection and replication in airway epithelial cells and sensory neurons may induce changes in neuronal phenotype and function determining chronic neurogenic cough through vagus nerve neuropathy [40]. Several observations indicate that Long-COVID is an heterogenous condition, with possible distinct pathogenetic pathways responsible for its different manifestations, and with a multitude of mechanisms potentially involved, such as SARS-CoV-2 persistence, immune dysregulation, autoimmunity, reactivation of other viruses such as EBV and HHV-6, and direct tissue and organ damage caused by the virus [33, 41].

The interpretation of the results should consider different factors. Antivirals were almost entirely represented by remdesivir. This may reduce the generalizability of the results to other drugs of this class, including molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir, that were received by only a few cases. Among drug classes, monoclonal antibodies were received less frequently than other treatments, and this may have reduced the likelihood to detect significant differences for this group.

In general, adjusting for several different covariates in multivariate analyses was a key element in the study design, but the need to include in each model only cases with available information on all covariates may have reduced the statistical power to detect significant differences. Although we cannot exclude that the loss of significance in the multivariate analyses may partly be the consequence of the decreased case volume, the models maintained large numbers (on average 1154 cases), and the proportion of excluded cases (24.8%) can be considered limited considering the high number of covariates included in the models. Outcomes which involved less than 20 cases were also excluded, and we therefore did not assess four symptoms infrequently observed (menstrual disorders, chilblains, delirium/hallucinations, fever).

A possible study limitation is represented by the retrospective symptom assessment in the majority of cases, which is however common to most of the published studies [14-16, 19-21, 23, 24, 37]. We also had information on the individual drug used only for the category of antivirals and were therefore unable to explore possible differences among specific drugs belonging to the other three categories. Our study was also not designed to evaluate the efficacy of the considered treatments on the course of acute disease, and the different individual response in this phase may also have affected subsequent symptom persistence. We also did not assess the role of some immunomodulating therapies such as JAK inhibitors, IL-1R antagonists, tyrosine kinase inhibitors and TNFα inhibitors, that more recently entered clinical evaluation as possible treatments of some Long-COVID conditions [42]. Finally, some selection bias is possible. Compared to the general population infected by SARS-CoV-2, our study sample was characterized by frequent occurrence of advanced age and severe acute COVID-19. Within this selected population differences might be more difficult to identify. We adjusted for several covariates, that included age, comorbidities and disease severity, but cannot exclude that younger and healthier populations, although less likely to receive pharmacological treatment for acute COVID-19, might respond more favorably to treatments in acute phase, and have better outcomes in the long-term.

The strengths of the present study include the evaluation of the potential protective impact of four different drug classes commonly used in acute COVID-19, the use of a wide array of covariates for adjusting risk estimates, the use of clinical and not of administrative data, with symptom information directly collected from patients, the use of a COVID-19-specific WHO questionnaire, and a longer follow up compared to studies that usually followed patients for no longer than three or six months [14-17, 19-24, 37].

In conclusion, examining the potential protective effect on Long-COVID of four drug classes administered during acute COVID-19, we found some protective associations in univariate analyses, that were however not maintained adjusting for confounders in multivariate analyses. For systemic corticosteroids and IL-6 inhibitors, some negative associations were found for isolated symptoms. Clinicians should consider the possibility of increased risk of some particular Long-COVID symptoms with use of such drugs in acute infection, balancing such potential long-term risk with the expected benefits on the course of acute disease.

The ISS Long-Covid Study Group:

Graziano Onder, Marco Floridia, Marina Giuliano, Tiziana Grisetti, Flavia Pricci, Tiziana Grassi, Dorina Tiple, Marika Villa, Liliana Elena Weimer, Cosimo Polizzi, Fabio Galati (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy); Maria Rosa Ciardi, Patrizia Pasculli (Dipartimento di Sanità Pubblica e Malattie Infettive, Università La Sapienza, Roma); Piergiuseppe Agostoni, Francesca Colazzo, Irene Mattavelli, Elisabetta Salvioni (Centro Cardiologico Fondazione Monzino, Milano e Dipartimento di Scienze Cliniche e di Comunità, Università degli Studi di Milano); Paolo Palange, Daniela Pellegrino, Marco Bezzio, Federica Olmati, Arianna Sanna, Arianna Schifano, Dario Angelone, Antonio Fabozzi (Dipartimento di Sanità Pubblica e Malattie Infettive, Università La Sapienza, Roma); Patrizia Rovere Querini, Simona Santoro, Anna Fumagalli, Aurora Merolla, Valentina Canti, Maria Pia Ruggiero, Marco Messina, Marina Biganzoli (U.O. Medicina Generale ad Indirizzo Specialistico e della Continuità Assistenziale, IRCCS Ospedale S. Raffaele, Milano); Danilo Buonsenso (Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Roma); Silvia Zucco, Alice Ianniello (ASL Città di Torino, Ospedale Amedeo di Savoia, Torino); Matteo Tosato, Vincenzo Galluzzo, Laura Macculi (Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Roma); Aldo Lo Forte, Valeria Maria Bottaro (USL Toscana Centro, Ospedale S. Giovanni di Dio Torregalli, Firenze); Paolo Bonfanti, Luca Bonaffini, Anna Spolti, Nicola Squillace (Unità di Malattie Infettive, Fondazione IRCCS San Gerardo dei Tintori, Monza); Donato Lacedonia, Terence Campanino (AOU OORR Foggia Pneumologia, Dipartimento di Scienze Mediche e Chirurgiche, Università di Foggia); Emanuela Barisione, Teresita Aloè, Elena Tagliabue (IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genova); Stefano Figliozzi, Federica Testerini (Ospedale di Ricerca IRCCS Humanitas, Rozzano); Paola Andreozzi, Marzia Miglionico, Antonia Barbitta, Chiara Cenciarelli (Unità di Medicina Predittiva, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Policlinico Umberto I and Dipartimento di Medicina Interna, Scienze Endocrino-Metaboliche e Malattie Infettive Università La Sapienza, Roma); Gianluca Pagnanelli, Giuseppe Piccinni (Istituto Dermopatico dell’Immacolata - IDI IRCCS - Roma); Paola Gnerre, Eugenia Monaco, Sandra Buscaglia, Antonella Visconti (ASL Liguria 2, Medicina Interna, Ospedale S. Paolo, Savona); Kwelusukila Loso (Ospedale di Manduria, ASL TA); Giuseppe Pio Martino, Giuseppina Bitti, Laura Postacchini, Antonella Cognigni (U.O.C. Medicina Interna, Ospedale “A. Murri”, Fermo); Maria Antonietta di Rosolini, Sergio Mavilla (UOSD di Malattie Infettive, PO Giovanni Paolo II, Ragusa); Domenico Maurizio Toraldo (Polo Riabilitativo, Plesso S. Cesario, Ospedale di Lecce); Guido Vagheggini, Giulio Bardi, Giuseppa Levantino (Azienda USL Toscana Nord Ovest); Cristina Stefan, Andrea Martinuzzi (IRCCS Eugenio Medea, Polo Scientifico Veneteo, Pieve di Soligo); Gianfranco Parati, Elisa Perger (IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Università di Milano Bicocca, Milano), Davide Soranna, Enrico Gianfranceschi, Francesca Pozzoli (IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano); Sara Grignolo (ASL Liguria 2, Struttura Complessa Malattie Infettive, Ospedale S. Paolo, Savona); Caterina Monari (AOU Unicam Vanvitelli, Napoli); Leila Bianchi, Luisa Galli (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Meyer, Firenze); Lorenzo Surace, Elisabetta Falbo (Centro Medicina del Viaggiatore e delle Migrazioni, Dipartimento di Prevenzione PO Lamezia Terme, ASP Catanzaro); Silvia Boni (S.C. Malattie Infettive, EO Ospedali Galliera, Genova); Claudia Battello (Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Friuli Centrale, Medicina Latisana, PO Palmanova,); Caterina Baghiris (SC Pneumologia ASL Friuli Occidentale, Pordenone); Gaetano Serviddio (UOC di Epatologia, AOU OO RR, Foggia).

Conflicts of interest

None. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be considered as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

The study is part of the project “Analysis and strategies of response to the long-term effects of COVID-19 infection (Long-COVID)” funded by the National Center for Disease Prevention and Control of the Italian Ministry of Health in 2021 (Grant I85F21003410005) and approved by the Ethics Committee of the ISS (ref. PRE BIO CE 01.00 0015066, 2022). The study sponsor had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fabio Galati, IT services, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy, for implementing the online platform used for data collection and for data management and extraction; Tiziana Grisetti and Katia Salomone, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy, for administrative support; Cosimo Polizzi, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy, for data management during all the study.

MF was responsible for data acquisition, directly accessed and verified the underlying data reported in the manuscript, performed the analyses and drafted the manuscript. LEW was responsible for data acquisition. MF and GO were responsible for study design and conceptualization. LEW, ALF, PP, MRC, PRQ, PA, EB, SZ, PA, PB, SF, MT, DL, KL, PG, MADR, DMT, GPM, GV, GP and The ISS Long-COVID Study Group contributed to the data acquisition. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results and review of the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and accepted responsibility to submit for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The study data can be made available upon reasonable request. Ethics Committee consultation may be necessary in order to obtain permission to share. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to marco.floridia@iss.it.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Italian National Ethics Committee approved the project (AOO-ISS-19/04/2022–0015066 Class: PRE BIO CE 01.00). Written informed consent was required for patient inclusion, using a patient information and consent form also approved by the Italian National Ethics Committee.

REFERENCES

[1] World Health Organization (WHO). Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID). 7 December 2022. Available at: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition. Accessed March 3rd, 2025.

[2] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE Guideline, No. 188, 2020 Dec 18: COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19.

[3] Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC). Long COVID basics. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/long-term-effects/index.html#:~:text=Long%20COVID%20is%20defined%20as,%2C%20worsen%2C%20or%20be%20ongoing. Accessed March 3rd, 2025.

[4] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Global Health; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on Examining the Working Definition for Long COVID; Goldowitz I, Worku T, Brown L, Fineberg HV, editors. Washington (DC): A Long COVID Definition: A Chronic, Systemic Disease State with Profound Consequences. National Academies Press (US); 2024 Jul 9.

[5] Petrakis V, Rafailidis P, Terzi I, et al. The prevalence of long COVID-19 syndrome in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Infez Med. 2024; 32(2): 202-212. doi: 10.53854/liim-3202-8

[6] Staffolani A Iencinella V, Cimatti M, Tavio M. Long Covid-19 syndrome as a fourth phase of Sars-CoV2 infection. Infez Med. 2022; 30(1): 22-29. doi: 10.53854/liim-3001-3

[7] Diaczok B, Nair G, Lin CH, et al. Evolution of prescribing practices and outcomes in the COVID-19 pandemic in metropolitan area. Infez Med. 2022; 30(1): 86-95. Doi: 10.53854/liim-3001-10.

[8] Woodrow M, Carey C, Ziauddeen N, et al. Systematic Review of the Prevalence of Long COVID. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023; 10(7): ofad233. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofad233.

[9] European Center for Disease prevention and Control (ECDC) . Prevalence of post COVID-19 condition symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort study data, stratified by recruitment setting. 27 October 2022. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Prevalence-post-COVID-19-condition-symptoms.pdf. Accessed March 3rd, 2025.

[10] Calvo Ramos S, Maldonado JE, Vandeplas A, Ványolós I, European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. Long COVID: A Tentative Assessment of Its Impact on Labour Market Participation and Potential Economic Effects in the EU. Available at: https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/long-covid-tentative-assessment-its-impact-labour-market-participation-and-potential-economic_en. Accessed March 3rd, 2025.

[11] Proal AD, Aleman S, Bomsel M, et al. Targeting the SARS-CoV-2 reservoir in long COVID. Lancet Infect Dis. 2025; 25(5): e294-e306. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00769-2.

[12] Sun G, Lin K, Ai J, Zhang W. The efficacy of antivirals, corticosteroids, and monoclonal antibodies as acute COVID-19 treatments in reducing the incidence of long COVID: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2024; 30(12): 1505-1513. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2024.07.006.

[13] Badenes Bonet D, Caguana Vélez OA, Duran Jordà X, et al. Treatment of COVID-19 during the Acute Phase in Hospitalized Patients Decreases Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2023; 12(12): 4158. doi: 10.3390/jcm12124158.

[14] Bertuccio P, Degli Antoni M, Minisci D, et al. The impact of early therapies for COVID-19 on death, hospitalization and persisting symptoms: a retrospective study. Infection. 2023; 51(6): 1633-1644. doi: 10.1007/s15010-023-02028-5.

[15] Chuang CH, Wang YH, Yeh LT, Yeh CB. Long-Term Stroke and Mortality Risk Reduction Associated With Acute-Phase Paxlovid Use in Mild-to-Moderate COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2025; 97(4): e70351. doi: 10.1002/jmv.70351.

[16] Congdon S, Narrowe Z, Yone N, et al. Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir and risk of long COVID symptoms: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2023; 13(1): 19688. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-46912-4.

[17] Durstenfeld MS, Peluso MJ, Lin F, et al. Association of nirmatrelvir for acute SARS-CoV-2 infection with subsequent Long COVID symptoms in an observational cohort study. J Med Virol. 2024; 96(1): e29333. doi: 10.1002/jmv.29333.

[18] Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Franco-Moreno A, Ruiz-Ruigómez M, et al. Is Antiviral Treatment with Remdesivir at the Acute Phase of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Effective for Decreasing the Risk of Long-Lasting Post-COVID Symptoms? Viruses. 2024; 16(6): 947. doi: 10.3390/v16060947.

[19] Joo H, Kim E, Huh K, et al. Risk of postacute sequelae of COVID-19 and oral antivirals in adults aged over 60 years: A nationwide retrospective cohort study. Int J Infect Dis. 2025; 154: 107850. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2025.107850.

[20] Liu TH, Chuang MH, Wu JY, et al. Effectiveness of oral antiviral agents on long-term cardiovascular risk in nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19: A multicenter matched cohort study. J Med Virol. 2023; 95(8): e28992. doi: 10.1002/jmv.28992.

[21] Patel R, Dani SS, Khadke S, et al. Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir for Acute COVID-19 in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease and Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JACC Adv. 2024; 3(6): 100961. doi: 10.1016/j.jacadv.2024.100961.

[22] Patrick-Brown TDJH, Barratt-Due A, Trøseid M, et al. The effects of remdesivir on long-term symptoms in patients hospitalised for COVID-19: a pre-specified exploratory analysis. Commun Med (Lond). 2024; 4(1): 231. doi: 10.1038/s43856-024-00650-4.

[23] Wang H, Wei Y, Hung CT, et al. Association of nirmatrelvir-ritonavir with post-acute sequelae and mortality in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024; 24(10): 1130-1140. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00217-2.

[24] Wee LE, Lim JT, Tay AT, et al. Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir treatment and risk for postacute sequelae of COVID-19 in older Singaporeans. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2025; 31(1): 93-100. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2024.08.019.

[25] Xie Y, Choi T, Al-Aly Z. Association of Treatment With Nirmatrelvir and the Risk of Post-COVID-19 Condition. JAMA Intern Med. 2023; 183(6): 554-564. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.0743.

[26] Velati D, Puoti M. Real-world experience with therapies for SARS-CoV-2: Lessons from the Italian COVID-19 studies. Infez Med. 2025; 33(1): 64-75. doi: 10.53854/liim-3301-6

[27] Alfano G, Morisi N, Frisina M, et al. Awaiting a cure for COVID-19: therapeutic approach in patients with different severity levels of COVID-19. Infez Med. 2022; 30(1): 11-21. doi: 10.53854/liim-3001-2

[28] Post COVID-19 CRF from the WHO Global Clinical Platform for COVID-19. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-covid-19-clinical-platform-case-report-form-(crf)-for-post-covid-conditions-(post-covid-19-crf-). Accessed March 3rd, 2025.

[29] Italian Medicines Agency. Use of antivirals for COVID-19. Available at: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/uso-degli-antivirali-orali-per-covid-19#:~:text=Veklury%20(remdesivir)%20%C3%A8%20il%20primo,pari%20ad%20almeno%2040%20kg). Accessed June 4, 2025.

[30] Italian Medicines Agency. Sarilumab in the treatment of adult patients with COVID-19. Available at: https://www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/1123276/Sarilumab_28.09.2021_EN.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2025.

[31] Italian Medicines Agency. Use of monoclonal antibodies for COVID-19. Available at: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/uso-degli-anticorpi-monoclonali. Accessed June 4, 2025.

[32] Castriotta L, Onder G, Rosolen V, et al. Examining potential Long COVID effects through utilization of healthcare resources: a retrospective, population-based, matched cohort study comparing individuals with and without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Public Health. 2024; 34(3): 592-599. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckae001.

[33] Castanares-Zapatero D, Chalon P, Kohn L, et al. Pathophysiology and mechanism of long COVID: a comprehensive review. Ann Med. 2022; 54(1): 1473-1487. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2076901.

[34] Namie H, Takazono T, Kawasaki R, et al. Analysis of risk factors for long COVID after mild COVID-19 during the Omicron wave in Japan. Respir Investig. 2025; 63(3): 303-310. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2025.02.008.

[35] Geng LN, Bonilla H, Hedlin H, et al. Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir and Symptoms in Adults With Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: The STOP-PASC Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2024; 184(9): 1024-1034. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.2007.

[36] Sawano M, Bhattacharjee B, Caraballo C, et al. Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir versus placebo-ritonavir in individuals with long COVID in the USA (PAX LC): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2, decentralised trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2025; 25(8): 936-946. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(25)00073-8.

[37] Quaranta VN, Portacci A, Dragonieri S, et al. The predictors of long COVID in Southeastern Italy. J Clin Med 2023; 12(19): 6303. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196303.

[38] Visconti NRGDR, Cailleaux-Cezar M, Capone D, et al. Long-term respiratory outcomes after COVID-19: a Brazilian cohort study. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2022; 46: e187. https://doi.org/10.26633/rpsp.2022.187.

[39] Geng Z, Yu Y, Hu S, Dong L, Ye C. Tocilizumab and the risk of respiratory adverse events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019; 37(2): 318-323.

[40] Song WJ, Hui CKM, et al. Confronting COVID-19-associated cough and the post-COVID syndrome: role of viral neurotropism, neuroinflammation, and neuroimmune responses. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9(5): 533–44. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00125-9.

[41] Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023; 21(3): 133-146. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2.

[42] Vlaming-van Eijk LE, Tang G, Bourgonje AR, et al. Post-COVID-19 condition: clinical phenotypes, pathophysiological mechanisms, pathology, and management strategies. J Pathol. 2025; 266(4-5): 369-389. doi: 10.1002/path.6443