Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 4, 382-390, 2025

doi: 10.53854/liim-3304-3

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Symptom-Based Active Tuberculosis Screening in Two Nigerian Correctional Facilities: A Cross-Sectional Study

Victor Abiola Adepoju1, Olusola Daniel Sokoya2, Safayet Jamil3,4, Masoud Mohammadnezhad5, Faisal Muhammad3, Abdulrakib Abdulrahim6, Hafiz T.A. Khan7,8

1 Department of HIV and Infectious Diseases, Jhpiego Nigeria (affiliate of Johns Hopkins University), Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, Nigeria;

2 Lagos State Tuberculosis, Buruli Ulcer and Leprosy Control Program, Ikeja, Lagos, Nigeria;

3 Department of Public and Community Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Frontier University Garowe (FUG), Puntland, Somalia;

4 Department of Public Health, Daffodil International University, Dhaka, Bangladesh;

5 Faculty of Health, Education and Life Sciences, Birmingham City University, Birmingham, UK;

6 Department of Medical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia;

7 College of Nursing, Midwifery and Healthcare, University of West London, UK;

8 Oxford Institute of Population Aging, University of Oxford, UK.

Article received 9 July 2025 and accepted 16 September 2025

Corresponding author

Safayet Jamil

E-mail: safayetkyau333@gmail.com

SUMMARY

Background: Tuberculosis (TB) remains a pressing health challenge in Nigerian correctional facilities, where the prevalence can be ten times higher than in the general population. Many facilities rely on passive TB case detection, often missing asymptomatic TB cases. This study evaluated a systematic active case-finding (ACF) approach using symptom-based screening followed by GeneXpert MTB/RIF testing across two high-volume Nigerian correctional facilities in Lagos and Ogun States.

Methods: Between April and September 2021, 2,244 inmates underwent standardized TB symptom screening (e.g., cough ≥2 weeks, weight loss, fever). Individuals with presumptive symptoms of TB provided sputum for GeneXpert analysis. The intervention comprised three strategies: (1) outreach screening in awaiting-trial mass cells, (2) cell-to-cell active case search, and (3) contact tracing of confirmed TB cases. Collected data were analysed to determine detection rates per 100,000 inmates and the overall positivity yield. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Lagos and Ogun State Ministries of Health, with formal permission granted by authorities of correctional facilities.

Results: Of the 2,244 inmates screened, 678 were identified as presumptive and tested, 45 were confirmed TB cases with estimated prevalence of 0.5% (approximately 489 per 100,000 inmates). The estimated prevalence is more than double the national prevalence 0.2% (219 per 100,000). The overall TB positivity rate among presumptive inmates was 7%. Inmates from Lagos recorded a TB point prevalence of 500 per 100,000, while prevalence in Ogun state was 458 per 100,000. A targeted outreach in one facility achieved a 32% TB yield. All detected TB cases were rifampicin-sensitive, and no drug-resistant strains was found in this cohort.

Conclusions: These findings highlight the effectiveness of symptom-based GeneXpert screening within correctional facilities which was substantially higher that conventional passive TB detection rates. All confirmed TB cases (n = 45) were rifampicin-sensitive, and no MDR or XDR strains were identified, an important observation in the prison environment. Regular, systematic ACF, especially in overcrowded and high-turnover environments, can significantly enhance early TB diagnosis and treatment initiation. Policymakers should institutionalize routine ACF in correctional facilities through universal entry screening for all new admissions and at least annual facility-wide screening, with symptom checklists plus rapid molecular testi. Where feasible, this should be combined with portable digital CXR/CAD triage alongside improvement in living conditions and post-release linkage to DOTS.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Symptom-based screening, GeneXpert MTB/RIF, Nigerian correctional facilities, active case finding.

BACKGROUND

Tuberculosis remains a leading cause of mortality, impacting individuals in the general population as well as those in institutionalized settings [1, 2]. The global fight against tuberculosis (TB) remains urgent, with the 2024 TB report estimating 10.8 million cases worldwide, including 8.2 million new diagnoses, and more than one million deaths attributed to the disease [2]. Among the most affected countries, Nigeria remains in the top 10 on all three high-burden lists: TB, HIV-associated TB, and MDR-TB [2, 3]. Globally, prisons reported approximately 125,000 new TB cases in 2019, but only 53% of infected inmates were identified, leaving a substantial proportion of inmates with TB undiagnosed or unreported [4]. Similar to the general population, TB incidence in prisons varies across WHO regions, with the African region reporting the highest rates [5].

The World Health Organization (WHO) strongly advocates for systematic tuberculosis (TB) screening among inmates and other individuals in penitentiary institutions [6, 7]. Screening in prisons should always include screening when a person enters a facility, followed by annual screening [8]. Previous study showed that only 0.9% of sputum samples collected from 13 Nigerian prisons tested positive for TB using an Acid-Fast Bacilli (AFB) smear [9]. In many Nigerian prisons, health care is largely limited to passive case detection, whereby symptomatic inmates self-report [9]. Systematic entry screening is not uniformly practiced, resulting in delayed detection of TB among inmates. Linkages with state TB programs offered GeneXpert testing and treatment supplies, but the diagnostic process was not routinely implemented for all inmates.

Active case finding (ACF) of TB in prisons is crucial as it promotes early diagnosis and treatment, thereby disrupting the transmission chain. The prevalence of HIV among inmates is twice that of the general population, which could significantly drive TB incidence in prisons [10]. The “WHO’s End TB Strategy” recommends the involvement of the private sector through public-private partnership models and active case finding using rapid point-of-care diagnostic tests among vulnerable populations like prisoners [6, 11].

The burden of TB in prisons is 10 times higher than that in the general population [12]. Several factors contribute to this disparity, including HIV infection with poor viral suppression, substance use, poor nutritional status, smoking, overcrowding, inadequate or inaccessible medical care (exacerbated by COVID-19 disruptions), and limited knowledge of TB infection control among inmates and staff, conditions that are prevalent in prison environments [13–16]. Moreover, the situation is exacerbated by the emergence and spread of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB strains [3]. Prison congestion, especially in urban Nigeria, infrastructural constraints, staff shortages and high inmate turnover can further perpetuate TB transmission [17, 18].

This study investigates and discusses the outcomes of an active TB case finding across two high-volume Nigerian prisons in Lagos and Ogun States and the effects on TB case notification rates. It highlights the urgent need for systematic interventions to control and prevent TB in these high-risk settings.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design and setting

Prior to the study, in collaboration with the State TB Program and Civil Society Organizations, we conducted advocacy and sensitization/awareness creation visits to prison authorities across two major prisons in Ogun and Lagos State. These two high-volume prisons were included in the final analysis. The total prison population at the time of screening was about 9,200 which represents the actual number of inmates rather than official capacity. High turnover and overcrowding were acknowledged but not directly factored into population-size calculations beyond noting that the 9,200 represented the census during screening. These prisons were selected based on their large inmate populations (i.e., 6,800 in Lagos and 2,400 in Ogun) and programmatic considerations, but do not represent all prisons in the country. The denominator (9,200) reflects the headcount of unique individuals present at the time of each screening round. Due to admissions, discharges, and transfers, we used cross-sectional counts rather than person-time. Turnover was not explicitly modelled, therefore, estimates represent point prevalence at screening rather than incidence over time.

Screening approach and intervention types

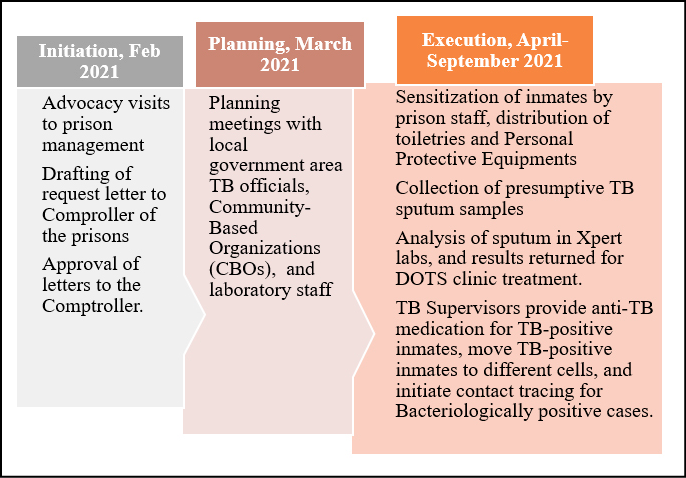

Five rounds of active case searches were implemented in a phased approach between April and September 2021. Outreach was chosen for large, awaiting-trial mass cells to reach many inmates quickly. Cell-to-cell was used for systematic coverage of all blocks once logistics permitted and to minimize missed symptomatic individuals. Three main strategies were used (Figure 1):

Figure 1 - Process Map for tuberculosis case finding in Nigerian prisons.

– Phase 1 – Prison Outreach: A mass screening program in awaiting-trial mass cells, involving direct engagement with inmates and on-site sputum collection.

– Phase 2 – Cell-to-Cell: Entailed actively searching for symptomatic TB by visiting each prison cell (“cell” refers to the primary housing space for inmates) and administering a symptom checklist for cough over two weeks, weight loss, etc.

– Phase 3 – Contact Investigation: Focused on screening inmates who shared living spaces (cells) or had prolonged exposure with confirmed TB cases.

Operational selection and key differences between phases

Phase 1 scenario (Outreach in awaiting-trial mass cells) used where very high cell density and time constraints required rapid coverage of large groups. During this phase, on-site sputum collection immediately followed symptom screen. Phase 2 (Cell-to-cell ACS) entails systematic screening of all cells to minimize missed cases, prioritized blocks with prior respiratory complaints/overcrowding and this was feasible when security/logistics allowed door-to-door screening. Phase 3 (Contact investigation) was triggered when an index case was confirmed. Contacts were defined operationally as cellmates or individuals sharing the same indoor sleeping space with the index case during the prior 2 weeks (see Key Definitions). Selection and sequencing were agreed with facility authorities to minimize disruption.

Key definitions

– A “TB case” was defined as any inmate presenting with clinical symptoms (e.g., cough ≥2 weeks, weight loss, fever, or night sweats) who tested GeneXpert MTB/RIF positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chest X-ray was not routinely performed due to resource constraints.

– ‘Contact’ is referred to an inmate who shared the same enclosed sleeping cell/airspace with an index case for ≥2 weeks (or ≥7 consecutive nights), or had daily cumulative exposure ≥8 hours/day during the 2 weeks preceding index diagnosis.”A “maximum security prison” is a facility with the highest level of security measures, designed to hold high-risk inmates with severe criminal histories [19].

– A “medium security prison” has a moderate level of security, allowing for somewhat more freedom of movement within the facility, typically used for inmates with less serious crimes or who have demonstrated good behaviour in prison [19].

Data collection and analysis

Inmates were clinically screened for cough ≥ two weeks, weight loss, fever, night sweats, chest pain, haemoptysis, fatigue/anorexia. Collected data, such as presumptive symptoms and demographic information, were documented in relevant recording and reporting tools. However, we note that usual practice involved passive case detection by prison health staff. Sputum was collected from symptomatic inmates and transported for GeneXpert analysis. In line with NTBLCP standard operating procedures, all testing used GeneXpert MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) on sputum. The state TB reference laboratory provided oversight for EQA while instrument calibration logs and lot-specific positive/negative controls were maintained per national QA protocols. Data were entered and analysed using Microsoft Excel and point prevalence estimation per 100,000 population.

Continuation of treatment

All inmates confirmed to have TB were initiated on DOTS (Directly Observed Treatment, Short-Course) within the prison. For inmates released or transferred prior to treatment completion, referral linkages to external DOTS centres were established to ensure continuity of care.

Ethical Clearance

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committees of the Lagos and Ogun State Ministries of Health, and the management of each prison granted permission. No personal identifiers were collected, and only aggregated data were used.

RESULTS

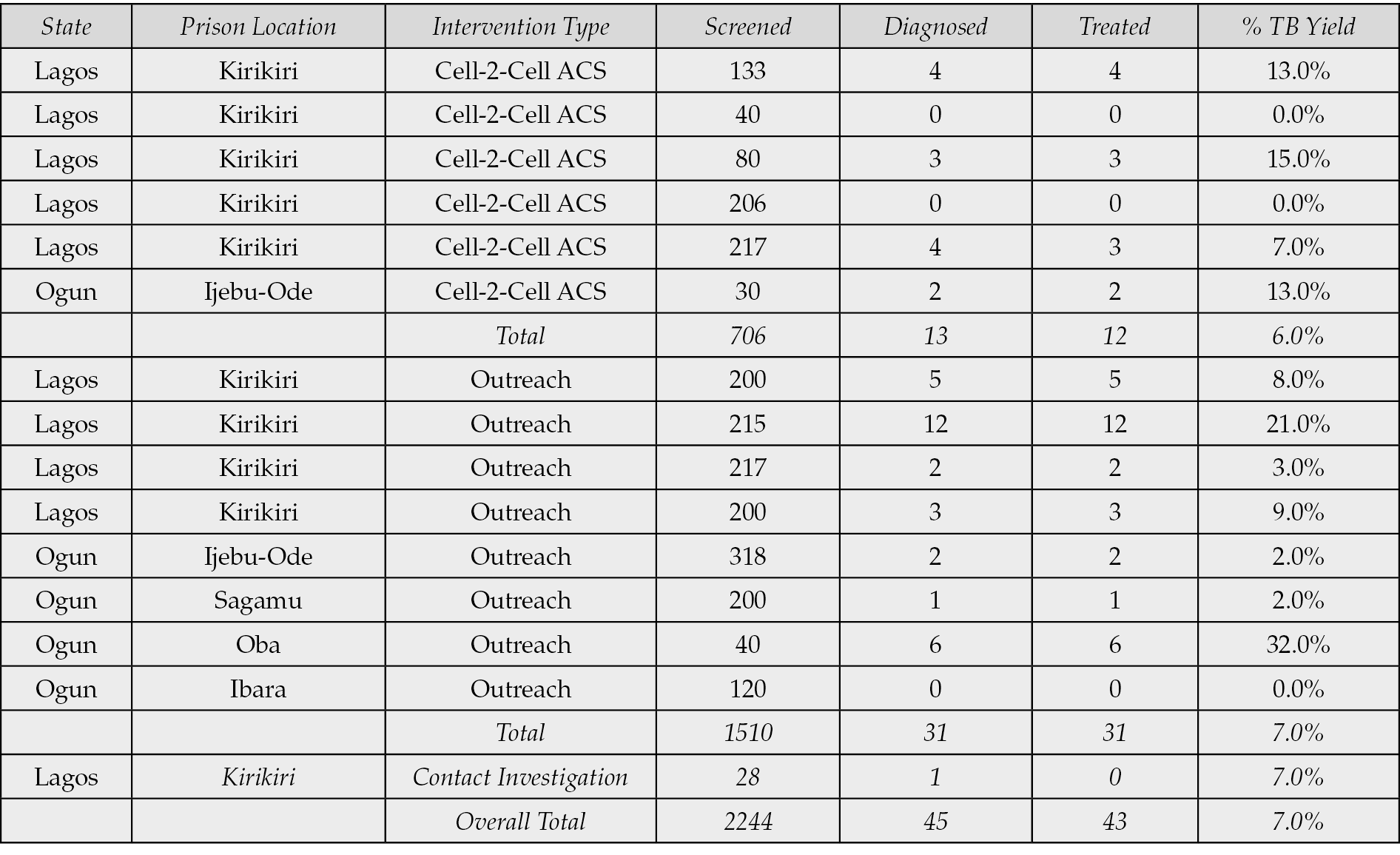

Table 1 shows the TB case-finding cascade in Nigerian prisons by intervention type from April to September 2021. In the Cell-to-Cell ACS approach at Kirikiri, Lagos, the TB yield fluctuated significantly, with 133 individuals screened and a 13.0% yield in one instance, but no cases were detected among 206 screened in another. In contrast, the outreach program at Kirikiri demonstrated high variability in TB yield, peaking at 21.0% with 215 individuals screened. Notably, the Oba prison in Ogun achieved a 32.0% yield from just 40 individuals screened, highlighting the effectiveness of targeted outreach interventions. Contact investigation identified 1 case among 28 contacts screened (3.6% yield) at Kirikiri, Lagos. Treatment initiation could not be confirmed before release/transfer, contributing to two total cases without documented DOTS initiation.

Table 1 - TB case finding cascade in Nigerian prisons by intervention types- April-September 2021.

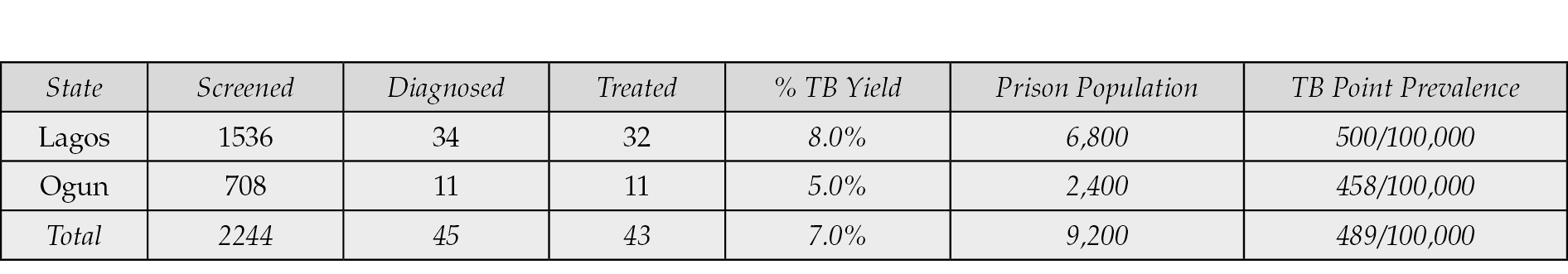

Table 2 shows tuberculosis case finding in Nigerian prisons, cascade, and point prevalence per 100,000 population by state. Across all interventions, 2,244 prisoners were screened, and 45 TB cases were identified. This corresponds to an overall detection rate of approximately 489 cases per 100,000 of the prison population. All 45 confirmed TB cases were rifampicin-sensitive, with no MDR or XDR detected.

Table 2 - Tuberculosis case finding in Nigeria prisons, cascade and point prevalence/100,000 pop by state.

DISCUSSION

Following active TB case finding (ACF) intervention in Nigerian correctional facilities, we found a TB point prevalence of 0.5% (489 cases per 100,000 population). This starkly contrasts with the lower national prevalence of approximately 219 cases per 100,000 population reported in 2020 when the study was conducted [20]. This disparity highlights the elevated risk and higher incidence of TB within incarcerated populations compared to the general population. Such elevated rates in correctional facilities have been consistently observed in various international settings which confirms that TB prevalence is often several-fold higher in correctional facilities than among the civilian population. For instance, previous studies have all reported significantly higher TB rates among inmates which ranges varies considerably from 6.4% in Zambia, 7.7% in Malaysia, 7.9% in Iran, 8.8% in South Africa, 10% in Nepal, 27.8% in Brazil [21–26]. These underscore the global challenge of TB management in correctional facilities. These studies also emphasize the inadequacy of traditional control measures like screening at entrance and active contact tracing in managing TB transmission within the congested and poorly ventilated environments typical of many correctional facilities.

Moreover, another study reported a TB prevalence of 8.8% (8,772 per 100,000) among inmates in the Mangaung Correctional Centre in South Africa. This was nine times higher than the prevalence in the general population [5]. A recent systematic review involving 59,300 prisoners from sub-Saharan African countries showed that approximately 4 in every 100 had tuberculosis, with a pooled prevalence estimated at 4.02% [21]. This extreme difference further illustrates the intense concentration of TB transmission within correctional facility settings, driven by overcrowding, poor ventilation, and suboptimal health services. Similarly, individuals in detention, including prisoners and undocumented migrants, constitute a vulnerable population requiring increased medical attention due to their elevated risk of delayed TB diagnosis and poorer treatment outcomes [27, 28].

The consistently higher prevalence rates in correctional facilities can be partly attributed to several key factors: the high turnover of inmates who may bring new infections into the facilities, the typical delays in diagnosis and initiation of treatment, and the challenges in implementing effective infection control measures [22]. The high TB rates reflect not only health system challenges but also the broader socio-economic conditions that affect marginalized populations both inside and outside of prison environments [16, 29]. The yield from contact tracing, which significantly contributed to the overall higher prevalence in our study, underscores the importance of comprehensive screening strategies within these populations. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that systematic screening can uncover a greater number of cases, particularly in high-risk environments like correctional facilities and hospital settings [1, 30, 31]. For instance, a retrospective study from Kuje prison in Abuja, Nigeria, which primarily utilized clinical assessment and chest X-rays for diagnosis, reported a substantially higher point prevalence of 2,393 per 100,000 population (2.4%) [32]. The retrospective nature of this study which spanned multiple years of data review, may have captured a cumulative incidence that presents a more severe epidemiological scenario compared to point-in-time studies. In addition, differences in study design likely account for part of the observed variance. The Kuje analysis used a retrospective, multi-year review with clinical and radiographic triage, which can over-represent cumulative detection relative to a point-prevalence approach. By contrast, our prospective cross-sectional ACF captured a snapshot of burden using symptom-triggered Xpert only, which is inherently less sensitive for subclinical disease. These design features should temper direct numerical comparisons. Similarly, other studies have shown that overcrowding, poor nutrition, and limited healthcare resources exacerbate TB transmission risks [17, 33].

In comparison, a recent survey of inmates at a correctional facility in Jos, North-Central Nigeria, found an overall TB prevalence of 12.2% [33]. The Jos study identified no rifampicin-resistant cases among the 11 TB-positive inmates which mirrors our findings where no resistant TB cases were detected. However, the Jos study recruited only 90 inmates total which is a small sample size. By contrast, our study involved a much larger prison population (2,244 inmates screened), which provides a more comprehensive estimate of 489/100,000. Therefore, while both studies observed no MDR or rifampicin-resistant TB, our ACF approach reached substantially more inmates, suggesting that prison-wide systematic screening in high-volume facilities can capture a broader snapshot of true TB burden.

Our study’s approach aligns with recommendations for TB control in correctional facilities which advocates for enhanced case-finding strategies that may include periodic systematic screenings and the use of rapid diagnostics like Xpert MTB/RIF® [3, 20]. Such strategies not only facilitate early diagnosis but could potentially reduce transmission rates within the incarcerated population, a critical concern given the closed and often overcrowded environments that are characteristic of this setting. Literature from Brazil, Ethiopia, and other sub-Saharan contexts further supports these measures with emphasis on the role of integrated screening in identifying a high burden of undiagnosed TB [34,35]. Interestingly, a 2023 study in Nigeria by Chukwuogo reported that digital chest X-ray combined with computer-aided detection for TB (CAD4TB) increased TB detection to 17%, compared with 5% using WHO symptom screening across 17 prisons in 12 states, and recommended integrating this approach into regular biannual prison screenings [36].

Some interventions in Nigerian correctional centres used a combination of portable digital X-ray plus GeneXpert to detect TB. For example, a study from Northern Nigeria reported a prevalence of about 1.1% at the Kano Central Correctional Centre the same approach as Chuckuogo to triage inmates [37]. They later confirmed cases with GeneXpert. Their approach identified at least one MDR-TB case (prevalence of 0.05% among all inmates screened). In contrast, our study which relied solely on symptom screening followed by GeneXpert, did not detect any drug-resistant cases. This discrepancy may reflect differences in screening sensitivity, or simply the random distribution of resistant strains. However, both studies underscore that routine active case finding in correctional settings can yield significantly higher detection rates than the baseline. In terms of yield, our 7% positivity rate among presumptive inmates was somewhat higher than what Tukur et al. [37], found in Kano, likely due to differences in prison demographics and screening algorithms.

Moreover, other mass screening initiatives that relied on universal chest radiography, as seen in Brazilian prisons often reported higher detection rates overall [35, 38]. In these interventions, chest X-ray was systematically applied to all inmates before GeneXpert testing, thus capturing individuals with subclinical or asymptomatic disease. By contrast, our study’s “symptoms first” approach may risk missing certain asymptomatic cases, though it remains more feasible in settings where X-ray equipment is limited. The Brazilian data suggest that including all inmates in Xpert testing, regardless of symptoms, could identify up to 74% of TB cases at a cost of US$ 249 per case [38]. Our study did not perform a cost analysis, but the relatively high detection rate of 489 per 100,000 indicates that even symptom-based strategies are beneficial in resource-limited environments.

Finally, data from Ethiopia, also reinforce that a variety of factors which range from crowded cells to low body mass index can impact TB vulnerability in incarcerated populations [39, 40]. In one Ethiopian study, the overall TB prevalence was 0.7% among all inmates but increased to 15.6% among symptomatic suspects [40]. Those investigators used GeneXpert for diagnosis, similar to our approach; however, they also identified potential risk factors like prior smoking and low BMI. Such findings complement our results and highlights the multifactorial nature of TB risk and the necessity for targeted interventions beyond diagnostics, including nutritional support and risk counselling. Another study from Ethiopian correctional facilities demonstrated that the proportion of microbiologically confirmed TB increased over time, likely reflecting delayed healthcare access and ongoing transmission [39]. These concerns are also relevant in Nigerian settings where overcrowding prolongs exposure.

Integrating robust TB screening and diagnostic practices into routine healthcare in correctional facilities is crucial for controlling the spread of TB in these high-risk settings [29]. The findings support systematic active screening of all inmates at regular intervals as part of a comprehensive TB control strategy, in line with the WHO’s End TB Strategy [6, 8]. Policies should also explore targeted approaches that address the unique TB risk factors in each prison setting to better guide control measures. Implementing global electronic record systems would further enable accurate data collection and sharing [41]. Moreover, improved living conditions, nutritional support, and stronger linkages between prisons and external TB programs could further diminish TB incidence [18].

Despite these advancements, our study has several limitations. Reliance solely on symptom-based screening and the absence of a control group may have underestimated diagnostic sensitivity. Future studies should consider incorporating portable chest radiography or CAD tools to improve detection of asymptomatic TB cases [42]. Similarly, due to lack of control group, it is difficult to attribute increases in case detection to specific interventions without potential confounding. Future research could include randomized controls or before-and-after comparisons to better quantify the impact of enhanced screening. The findings have important policy and practice implications.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings align with international evidence that TB risk is markedly increased in correctional environments. The comparisons above illustrate how differences in screening tools (e.g., portable digital X-ray vs. symptom-based GeneXpert testing) can yield slightly varied prevalence rates and detection of drug-resistant TB. Nonetheless, any robust ACF approach in correctional facilities reveals a substantially higher TB prevalence than reported among the general population. This reinforces the urgency for ongoing screening and comprehensive interventions to reduce TB transmission behind bars.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study has not received any external funding.

[1] Meregildo-Rodriguez ED, Ortiz-Pizarro M, Asmat-Rubio MG, Rojas-Benites MJ, Vásquez-Tirado GA. Prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) in healthcare workers in Latin America and the Caribbean: systematic review and meta-analysis. Infez Med. 2024; 32: 292-311. https://doi.org/10.53854/liim-3203-4.

[2] WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024 - TB incidence 2024. Available at: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024/tb-disease-burden/1-1-tb-incidence. (accessed August 12, 2025).

[3] Gulumbe BH, Abdulrahim A, Ahmad SK, Lawan KA, Danlami MB. WHO report signals tuberculosis resurgence: Addressing systemic failures and revamping control strategies. Decod Infect Transm. 2025; 3: 100044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcit.2025.100044.

[4] Martinez L, Warren JL, Harries AD, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of tuberculosis incidence and case detection among incarcerated individuals from 2000 to 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2023; e511-519. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00097-X.

[5] Nyasulu P, Mogoere S, Umanah T, Setswe G. Determinants of Pulmonary Tuberculosis among Inmates at Mangaung Maximum Correctional Facility in Bloemfontein, South Africa. Tuberc Res Treat. 2015; 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/752709.

[6] World Health Organization. The end TB strategy 2015. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HTM-TB-2015.19 (accessed August 12, 2025).

[7] World Health Organization. Tuberculosis: Systematic screening 2024. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/systematic-screening-for-tb (accessed August 12, 2025).

[8] World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2023 2023. Available at: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2023 (accessed August 12, 2025).

[9] Onu E, Enejoh VA, Olarewaju J, et al. What is the TB Burden in Nigerian Prisons? – An Enhanced TB Case Finding Program experience from 13 Nigerian Prisons. Ann Glob Health. 2017; 83: 61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2017.03.132.

[10] United Nations. National HIV Assessment: People in Nigerian prisons are twice more likely to live with HIV. UNODC Ctry Off Niger 2021. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/conig/en/stories/national-hiv-assessment_-people-in-nigerian-prisons-are-twice-more-likely-to-live-with-hiv.html (accessed August 12, 2025).

[11] Word Health Organization. Reach the 3 million: Find. Treat. Cure TB 2014. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/reach-the-3-million-find.-treat.-cure-tb (accessed August 12, 2025).

[12] Cords O, Martinez L, Warren JL, et al. Incidence and prevalence of tuberculosis in incarcerated populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2021; 6: e300-308. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00025-6.

[13] Jeremiah TA, Jacob RB, Jeremiah ZA, Mgbere O, Anyamene C, Enweani-Nwokelo IB. Burden of HIV, Tuberculosis Infection and Risk Factors amongst Inmates of Correctional Institutions in Port Harcourt Nigeria. Int J Trop Dis Health. 2021; 34-44. https://doi.org/10.9734/ijtdh/2021/v42i1030489.

[14] Onyekwena RPS, Agu TE, Boniface J, Tomen EA, John OT. Knowledge and Practice of Pulmonary Tuberculosis Prevention among in-Mates and Staff of Taraba State Correctional Centres. Int J Res Innov Appl Sci. 2023; VIII: 24–37. https://doi.org/10.51584/IJRIAS.2023.81102.

[15] Word Health Organization. TB in prisons 2024. Available at: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2023/featured-topics/tb-in-prisons (accessed August 12, 2025).

[16] Formenti B, Gregori N, Crosato V, Marchese V, Tomasoni LR, Castelli F. The impact of COVID-19 on communicable and non-communicable diseases in Africa: a narrative review. Infez Med. 2022; 30: 30-40. https://doi.org/10.53854/liim-3001-4.

[17] Joseph OE, Femi AF, Ogadimma A, et al. Prison overcrowding trend in Nigeria and policy implications on health. Cogent Soc Sci. 2021; 7: 1956035. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1956035.

[18] Onyemali CP, Ode DK, Madihi S. Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) and Hepatitis B and C Health Inequalities Among Male Prisoners in Nigeria: A Narrative Literature Review 2024. Preprint.org. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202408.0910.v2.

[19] Simwa A. Types of prison in Nigeria - Legit.ng 2019. Available at: https://www.legit.ng/1215919-types-prison-nigeria.html (accessed August 12, 2025).

[20] World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2020 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240013131 (accessed August 15, 2025).

[21] Asgedom SY, Ambaw Kassie G, Melaku Kebede T. Prevalence of tuberculosis among prisoners in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2023; 11: 1235180. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1235180.

[22] Valença MS, Scaini JLR, Abileira FS, Gonçalves CV, Von Groll A, Silva PEA. Prevalence of tuberculosis in prisons: risk factors and molecular epidemiology. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015; 19: 1182-1187. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.15.0126.

[23] Shrestha G, Yadav DK, Gautam R, Mulmi R, Baral D, Pokharel PK. Pulmonary Tuberculosis among Male Inmates in the Largest Prison of Eastern Nepal. Tuberc Res Treat. 2019; 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3176167.

[24] Al-Darraji HAA, Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A. Undiagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis among prisoners in Malaysia: an overlooked risk for tuberculosis in the community. Trop Med Int Health. 2016; 21: 1049-1058. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12726.

[25] Alavi SM, Bakhtiarinia P, Eghtesad M, Albaji A, Salmanzadeh S. A Comparative Study on the Prevalence and Risk Factors of Tuberculosis Among the Prisoners in Khuzestan, South-West Iran. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2014; 7. https://doi.org/10.5812/jjm.18872.

[26] Fuge TG, Ayanto SY. Prevalence of smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis and associated risk factors among prisoners in Hadiya Zone prison, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2016; 9:201. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-2005-7.

[27] Di Gennaro F, Cotugno S, Guido G, et al. Disparities in tuberculosis diagnostic delays between native and migrant populations in Italy: A multicenter study. Int J Infect Dis. 2025; 150: 107279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2024.107279.

[28] Cotugno S, Guido G, Segala FV, et al. Tuberculosis outcomes among international migrants living in Europe compared with the nonmigrant population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. IJID Reg. 2025; 14: 100564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijregi.2024.100564.

[29] Gulumbe BH, Abdulrahim A, Danlami MB. The United Nations’ ambitious roadmap against tuberculosis: opportunities, challenges and the imperative of equity. Future Sci OA. 2024; 10: 2418787. https://doi.org/10.1080/20565623.2024.2418787.

[30] Cunha EAT, Marques M, Evangelista MDSN, Pompilio MA, Yassuda RTS, Souza ASD. A diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis and drug resistance among inmates in Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2018; 51: 324-330. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0289-2017.

[31] Mabud TS, De Lourdes Delgado Alves M, Ko AI, et al. Evaluating strategies for control of tuberculosis in prisons and prevention of spillover into communities: An observational and modeling study from Brazil. PLOS Med. 2019; 16: e1002737. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002737.

[32] Lawal M, Omili M, Bello T, Onuha L, Haruna A. Tuberculosis in A Nigerian Medium Security Prison. Benin J Postgrad Med. 2009; 11. https://doi.org/10.4314/bjpm.v11i1.48840.

[33] Agabi Y, Uneze S, Ozioma O, et al. Prevalence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis among inmates of Nigerian correctional services centre, Jos, attending Faith Alive Foundation Hospital, Jos, Nigeria. Microbes Infect Dis. 2023; 4(3): 981-987 https://doi.org/10.21608/mid.2022.168438.1397.

[34] Rakpaitoon S, Thanapop S, Thanapop C. Correctional Officers’ Health Literacy and Practices for Pulmonary Tuberculosis Prevention in Prison. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19: 11297. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811297.

[35] Ribeiro CC, Santos ADS, Tshua DH, et al. Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in prisons in Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2023; 56:e0015-2023. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0015-2023.

[36] Chukwuogo O. Yield from active TB case-finding activities in prisons: implications for routine TB screening in Nigerian penitentiary institutions. Delft Imaging, Paris, France: Available at: https://delft.care/nigeria-active-tb-case-finding-in-prisons-with-delft-light-cad4tb-onestoptb-clinic/; 2023.

[37] Tukur M, Odume B, Bajehson M, et al. Outcome of Tuberculosis Case Surveillance at Kano Central Correctional Center, North-west Nigeria: A Need for Routine Active Case Findings for TB in Nigerian Correctional Centers. Int J Trop Dis Health. 2021: 37-45. https://doi.org/10.9734/ijtdh/2021/v42i1830536.

[38] Santos ADS, De Oliveira RD, Lemos EF, et al. Yield, Efficiency, and Costs of Mass Screening Algorithms for Tuberculosis in Brazilian Prisons. Clin Infect Dis. 2021; 72: 771-777. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa135.

[39] Amirkhani A, Humayun M, Ye W, Worku Y, Yang Z. Patient characteristics associated with different types of prison TB: an epidemiological analysis of 921 TB cases diagnosed at an Ethiopian prison. BMC Pulm Med. 2021; 21: 334. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01699-w.

[40] Ephrem K, Dessalegn Z, Etana B, Shimelis C. Prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis and associated factors among prisoners in Western Oromia, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. J Sci. 2022; Technology and Arts Research:27-40 Pages. https://doi.org/10.20372/STAR.V11I4.03.

[41] Nyasulu PS, Hui DS, Mwaba P, et al. Global perspectives on tuberculosis in prisons and incarceration centers - Risk factors, priority needs, challenges for control and the way forward. IJID Reg. 2025; 14: 100621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijregi.2025.100621.

[42] Macpherson L, Miller C, Hamada Y, et al. Policies, practices, opportunities and challenges for tuberculosis screening: a global survey of national tuberculosis programmes. BMJ Glob Health. 2025; 10: e016000. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2024-016000.