Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 4, 370-381, 2025

doi: 10.53854/liim-3304-2

REVIEWS

Epidemiology and seroprevalence of Hepatitis E Virus in Nigeria and its African context: a review and one health perspective

Babatunde Ibrahim Olowu1,2, Oluwaloni Bolaji Tinubu2, Oluwatomisin Omolola Solesi2, Emmanuel Ochi 3, Saheed Olaide Ahmed2, Maryam Ebunoluwa Zakariya4

1 Multidisciplinary Program in Infectious Diseases, Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Washington State University, USA;

2 Department of Veterinary Microbiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria;

3 Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria;

4 Edinburgh Medical School, College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

Article received 12 September 2025 and accepted 10 November 2025

Corresponding author

Zakariya Maryam Ebunoluwa

E-mail: M.E.Zakariya@sms.ed.ac.uk

SUMMARY

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is an under-recognised cause of acute viral hepatitis and remains a major public health concern in Africa. Worldwide, over 20 million HEV infections and nearly 3 million symptomatic cases occur annually, but the true extent in Africa is poorly understood due to limited surveillance, inconsistent diagnostics, gaps in blood safety, unclear zoonotic routes, low public awareness, and underreporting. Outbreaks in several African countries are often associated with floods, displacement, and poor sanitation. Seroprevalence studies show notable variation, from less than 1% in Tanzania to over 80% in Egypt, reflecting diverse epidemiological situations across the continent. In Nigeria, two major outbreaks have been reported, with evidence of widespread human exposure and high infection rates in pigs.

Addressing these issues requires a One Health approach that integrates human, veterinary, and environmental health systems. Priority interventions include expanding affordable diagnostics, strengthening Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) infrastructure, routine animal and blood donor screening, targeted education for high-risk groups, and investment in molecular epidemiology. Therefore, this review consolidates current knowledge of HEV in Africa, with insights from Nigeria, and provides recommendations for control through a coordinated One Health approach.

Keywords: Hepatitis E virus, Nigeria, One Health, zoonosis, epidemiology, surveillance, prevention

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is a globally significant cause of acute viral hepatitis, accounting for an estimated 20 million infections and over 3 million symptomatic cases annually [1]. HEV-induced hepatitis manifests as either acute or chronic viral hepatitis, transmitted through the ingestion of contaminated food or water via the enteric-fecal-oral route [2]. Although previously regarded as a self-limiting disease, HEV has garnered increasing attention owing to its severe clinical implications within vulnerable populations, including pregnant women and immunocompromised individuals, as well as its capacity to induce both sporadic cases and extensive waterborne outbreaks [3]. Mortality rates generally range from 1% to 2% among the general population but can surpass 40% during third-trimester pregnancies, with numerous reports documenting vertical transmission and adverse maternal-fetal outcomes [2-4].

HEV VIROLOGY AND TRANSMISSION ROUTES

HEV belongs to the family Hepeviridae and the genus Orthohepevirus, and is a small, icosahedral, non-enveloped virus with a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome measuring approximately 27–34 nm in diameter [5-7]. HEV transmission has been reported to occur through blood products and transplantation with asymptomatic organ or blood donors increasing the transmission risk to recipients [8, 9]. HEV can be divided into eight genotypes (GT) with some genotypes having both human and animal hosts, hence providing an opportunity for zoonotic transmission and disease spillovers [8, 10-12]. Zoonotic transmission of HEV usually involves the consumption of animals or animal products such as contaminated milk as well as undercooked or raw meat while feco-oral and is mainly through contaminated water [8, 13, 14]. There has been notable variations in diagnostic methods over the years with transitions being made from using just ELISA to the use of RT-qPCR and RT-PCR with variability in manufacturer of the individual assays accounting for variation in specificity and sensitivity of the test [15-17].

HEV outbreaks have been experienced in over half of sub-Saharan countries, including Egypt, Algeria, Nigeria, South Africa, Morocco and Tanzania, with most outbreaks often linked to seasonal flooding, displacement, and inadequate sanitation and inaccessibility to clean water [11, 12, 18-22]. These disparities collectively emphasize the severe public health challenge faced in several African countries [22]. In Nigeria, studies on HEV are limited due to patients’ preference for traditional medications and self-medication [23]. Nigeria, therefore, exemplifies a useful case study for understanding the African HEV burden and for developing targeted One Health interventions [21]. This review consolidates existing evidence on HEV epidemiology, diagnostics, challenges and prevention of HEV and proposes an adoptable One Health approach in tackling HEV in Nigeria and Africa as a whole.

METHODS

This review was developed through a systematic search of peer-reviewed literature on hepatitis E virus (HEV), with a special emphasis on Nigeria and the broader African context. Scholarly databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus, were queried between January and March 2025. Search terms combined medical subject headings (MeSH) and free text keywords such as: “Hepatitis E Virus,” “HEV,” “Nigeria,” “Africa,” “epidemiology,” “outbreak,” “seroprevalence,” “zoonosis,” “One Health,” and “prevalence.” Boolean operators (“AND” “OR”) were applied to refine results.

Inclusion Criteria

a) Studies published in English between 1990 and 2025.

b) Articles reporting human or animal HEV seroprevalence, outbreak investigations, or case series from Nigeria and Africa.

c) Reviews, surveillance reports, and policy papers relevant to HEV epidemiology, prevention, or One Health strategies.

Exclusion Criteria

a) Studies focusing on unrelated viral hepatitis (e.g., hepatitis A, B, C, D).

b) Case reports or studies lacking primary epidemiological or diagnostic data.

c) Duplicated reports are already included in systematic reviews unless they contributed additional local context.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

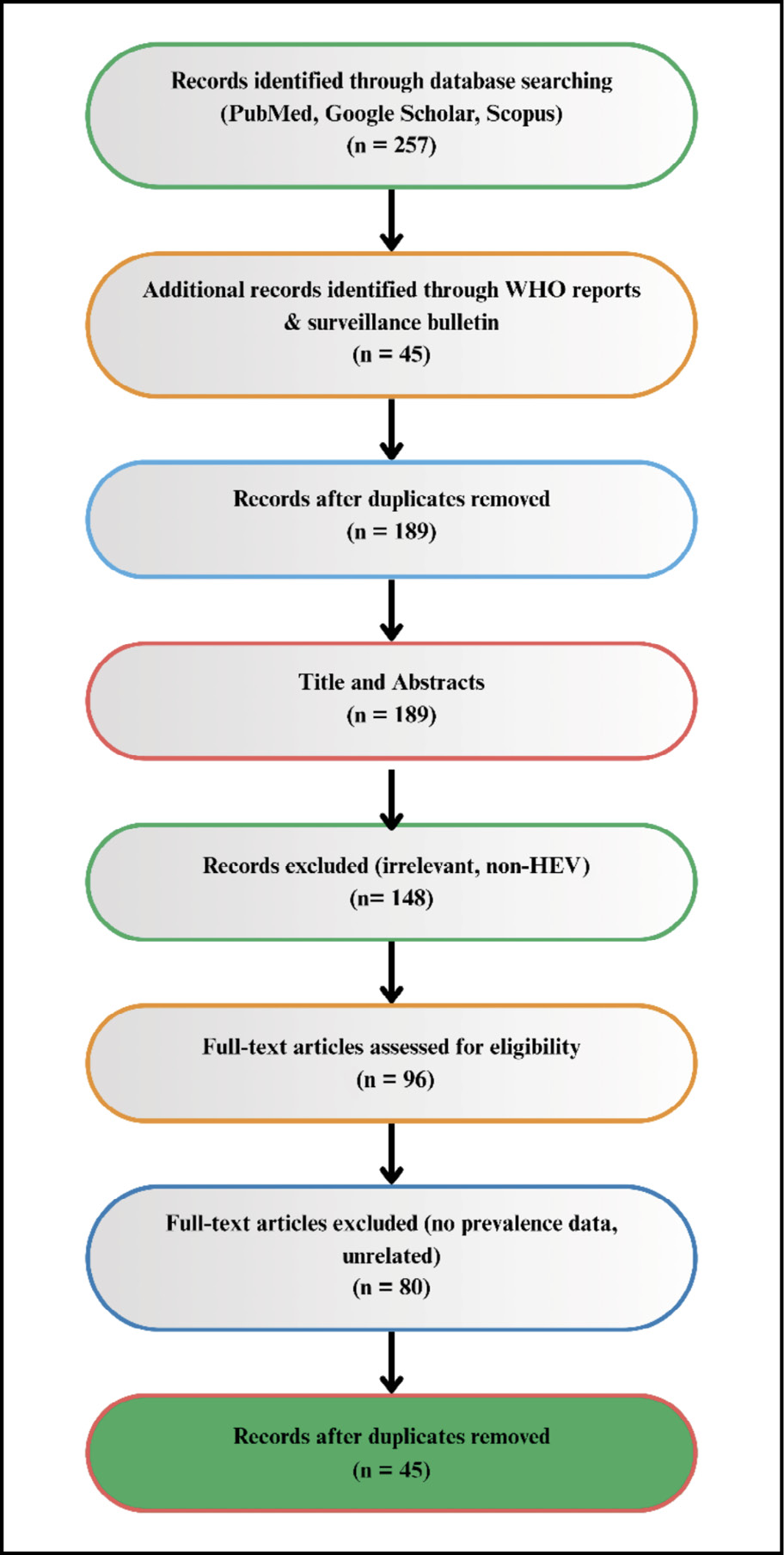

Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, and eligible full texts were reviewed in detail. Data extracted included study year, location, sample population, diagnostic method, seroprevalence, and key findings. To contextualize Nigerian findings, comparative African data were included, particularly from West African countries with similar ecological and socioeconomic conditions. Where available, results were cross-referenced with WHO fact sheets, national outbreak reports, and systematic reviews (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - PRISMA-style workflow for study selection.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Burden of HEV in Africa

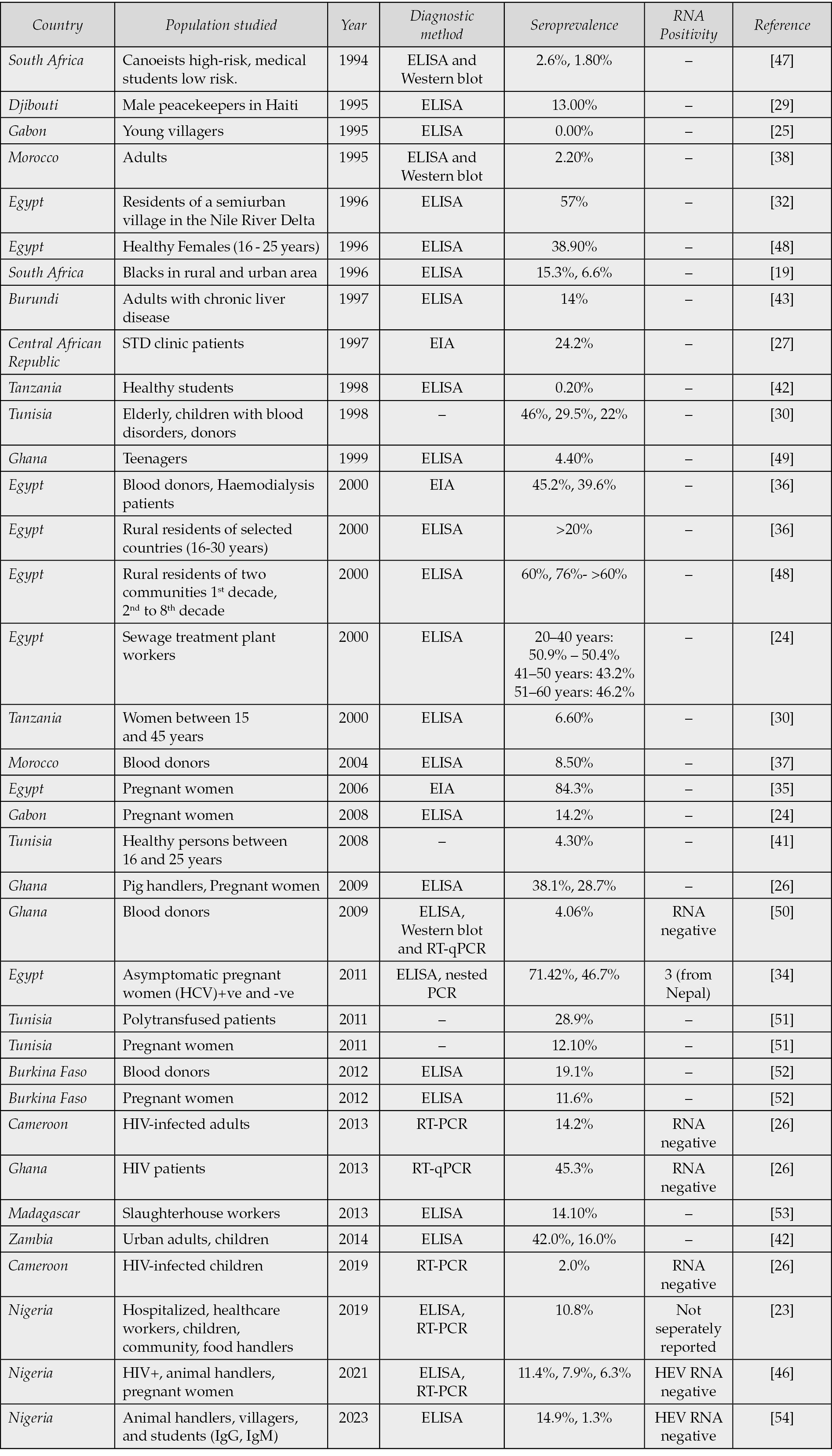

Across the African region, prevalence in West Africa was moderate to high; Central Africa was moderate, while Southern and Eastern Africa was low [24, 25].

Central Africa

In different studies conducted in Central Africa, variations in HEV prevalence were recorded across different demographics hence highlighting the influence of exposure risk and living conditions on infection dynamics. In Gabon, no antibodies were detected among young villagers while an approximate of 14% prevalence was recorded among pregnant women [24, 25]. Similarly, in Cameroon, a seroprevalence of 14.2% among HIV-infected adults and 2% among HIV-infected children was reported, indicating a moderate level of HEV exposure within immunocompromised populations [26]. However, in the Central African Republic, a high seroprevalence of 24% was documented among patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics, suggesting possible overlaps in transmission routes and shared behavioral risk factors [27].

Furthermore, the detection of HEV antibodies in non-human primates (NHP), particularly the Agile mangabey in Cameroon (28.6% anti-HEV IgM), reinforces the hypothesis of zoonotic reservoirs contributing to viral persistence and transmission in the region [28]. Collectively, these findings underscore the heterogeneous distribution of HEV infection across Central African populations and suggest potential interspecies transmission pathways that warrant further investigation.

Eastern Africa

In Djibouti, a seroprevalence of 13% was reported among male peacekeepers, reflecting substantial HEV exposure within this occupational group [29]. In Tanzania, a 6% seroprevalence was observed among women aged 15–45 years, whereas a markedly lower prevalence of 0.2% was documented among university students, representing one of the lowest rates reported in Africa [30, 31]. These findings illustrate pronounced heterogeneity in HEV exposure both within and between populations, which may be influenced by differences in environmental conditions, sanitation standards, behavioral factors, and levels of immunity. The contrasting prevalence rates across these demographic and geographic groups highlight the complex epidemiological landscape of HEV transmission in East Africa.

Southern Africa

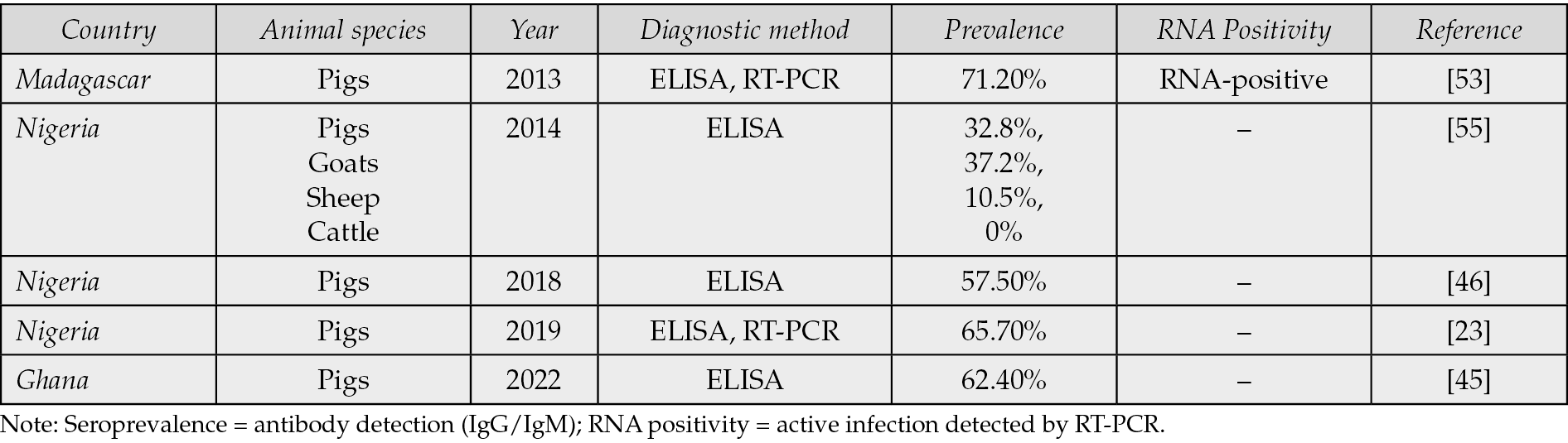

In Madagascar, a seroprevalence of 14% was reported among slaughterhouse workers, while a substantially higher rate of 71% was detected in pigs sampled from the same setting, underscoring the potential for occupational and zoonotic transmission [39]. In South Africa, studies have revealed a distinct rural-urban gradient, with higher HEV seroprevalence observed in rural populations, likely reflecting disparities in sanitation infrastructure and environmental exposure [19, 30]. These patterns support the strong association between environmental conditions, hygiene practices, and HEV circulation across African settings [31]. Furthermore, elevated seroprevalence has been reported among poly-transfused adults (28%) and pregnant women (12%), highlighting biological susceptibility and transfusion-related risks in regions lacking systematic blood screening [40]. In Zambia, prevalence rates of 16% among children and 42% among urban adults have been documented, further emphasizing age-related and urban exposure differentials in HEV transmission dynamics (Table 1a) [41, 42].

Table 1a - Human HEV seroprevalence and diagnostic methods in African countries.

Northern Africa

In North Africa, HEV seroprevalence remains consistently high, particularly in Egypt, where IgG positivity rates exceeding 60-80% have been documented across diverse population groups, including pregnant women, patients with chronic liver disease, and rural residents [32-36]. Such widespread exposure suggests that HEV infection is likely endemic and may be linked to environmental and sanitation-related factors that facilitate continuous transmission. In Morocco, however, reported rates are comparatively lower, with 8% seroprevalence among blood donors and approximately 2% among adults when assessed using ELISA and Western blot assays (Table 1a) [37, 38]. These variations indicate a geographical gradient in HEV exposure across North Africa, reflecting differences in population density, water quality, hygiene practices, and diagnostic methodologies employed in different studies

Western Africa

In Burkina Faso, HEV seroprevalence rates ranging from 10% to 19% have been reported among blood donors and pregnant women, indicating moderate exposure levels within the general population [19]. Among adults with chronic liver disease, a seroprevalence of 14% was observed, suggesting a possible association between HEV infection and pre-existing hepatic conditions [43]. In Ghana (Table 1a), studies have documented high seroprevalence levels, with approximately 45% detected by RT-PCR among HIV-positive patients and 4-38% across different subgroups of the general population [26, 44].

Serological investigations in pigs revealed prevalence rates exceeding 60%, pointing to the existence of animal reservoirs that may facilitate zoonotic transmission (Table 1b) [45].

Table 1b - Animal HEV seroprevalence and diagnostic methods in African countries.

Table 1b shows the existence of animal reservoirs that may facilitate zoonotic transmission and notes pigs to be the main animal reservoir.

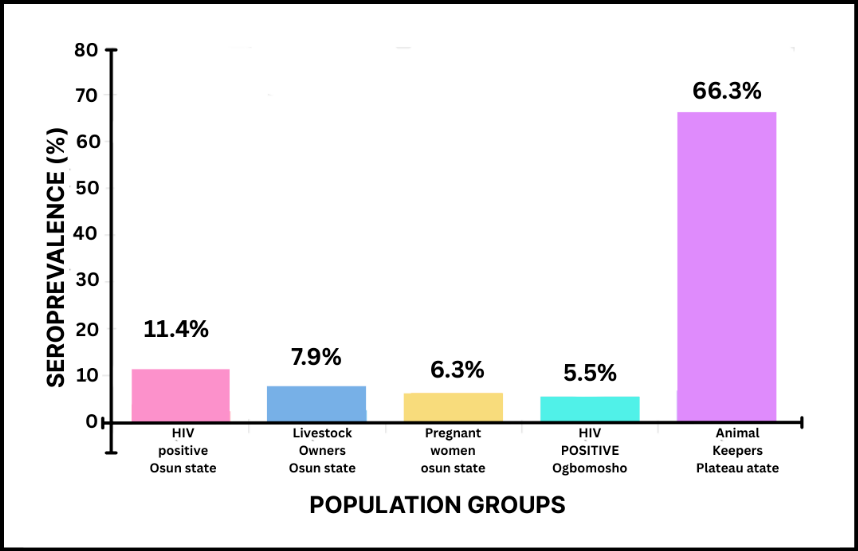

In Nigeria, Osundare et al. (2021) further advanced HEV research by identifying notably high seroprevalence rates among HIV-positive individuals (11.4%), animal handlers (7.9%), and pregnant women (6.3%), thereby confirming these groups as key high-risk cohorts within the country [46]. Collectively, these findings underscore the widespread circulation of HEV in West Africa, with significant variation by population subgroup, occupation, and comorbid status, reflecting complex ecological and socio-behavioral determinants of infection.

HEV in Nigeria

At-risk populations and gender variations

In Nigeria, Hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection affects individuals across all demographic groups; however, certain populations remain disproportionately vulnerable (Figure 2). The most affected groups are typically those residing in rural and peri-urban communities, where limited access to clean water, poor sanitation, and inadequate healthcare infrastructure facilitate ongoing viral transmission [56–58]. According to Osundare et al. (2021), HIV-positive individuals (11.4%), livestock owners (7.9%), and pregnant women (6.3%) exhibit the highest seroprevalence rates, highlighting environmental and biological risk factors that exacerbate exposure and disease severity.

Figure 2 - HEV Seroprevalence Among At-Risk Populations in Nigeria.

HEV infection is particularly severe in pregnant women, in whom it may result in acute liver failure or fulminant hepatic failure, contributing to significant maternal morbidity and mortality [46, 59, 60]. Similarly, food and animal handlers have been identified as important occupational risk groups, given their frequent contact with potentially infected animals and contaminated products [23]. This aligns with findings from Oluremi et al. (2023), who reported a 2.2% higher seroprevalence among individuals with animal contact and a notably high prevalence of 31.1% among butchers, underscoring the potential for zoonotic transmission [54]. Consistently, Osundare et al. (2020) documented a 7.9% seroprevalence among animal keepers in Osun State (Figure 2), further emphasizing the link between occupational exposure and HEV infection in Nigeria [57].

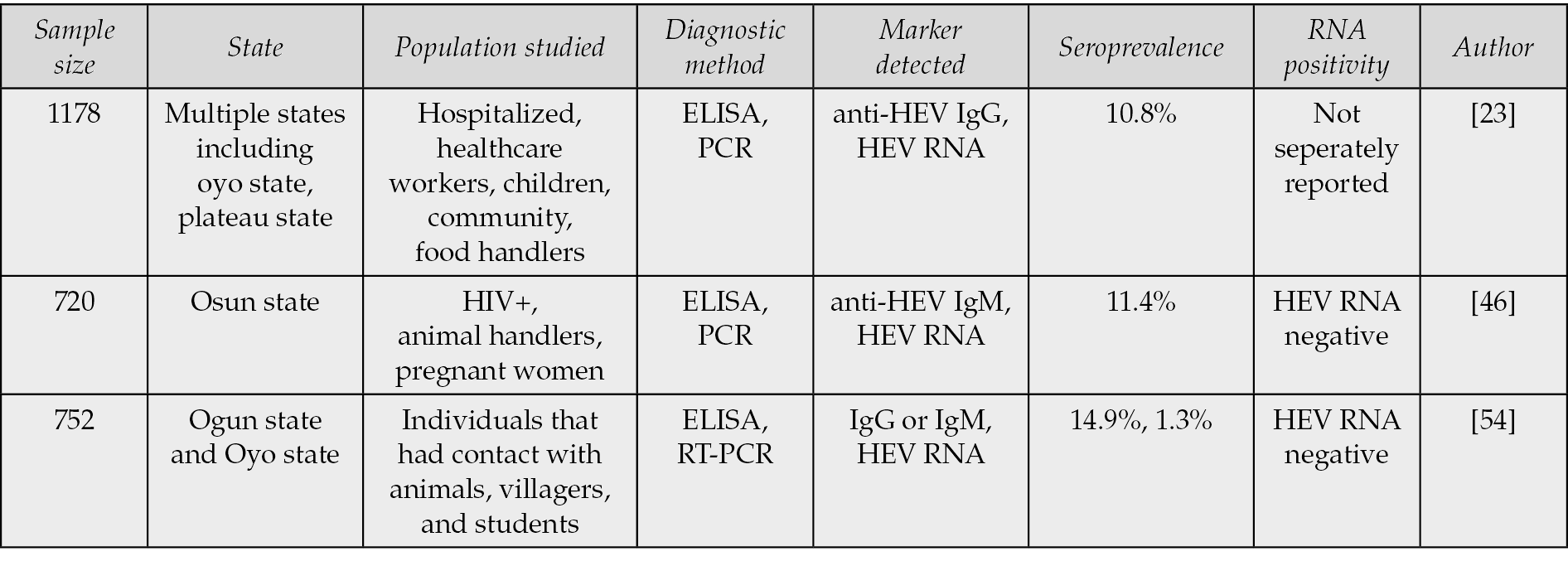

Gender-specific variations in HEV infection have also been observed. In a study of HIV-positive individuals, Osundare et al. (2021) reported a markedly higher anti-HEV IgM seroprevalence in men (6.5%) compared to women (0.7%), indicating that recent or ongoing infections may occur more frequently among males [46]. This observation aligns with earlier findings by Adesina et al. (2009), which similarly suggested male predominance in HEV exposure and transmission dynamics (Table 2a).

Table 2a - Human HEV seroprevalence and diagnostic methods in Nigeria.

Geographic variations

Marked geographical differences in HEV prevalence have been observed across Nigeria. Southern states, including Ekiti, Osun, and Ibadan, demonstrate moderate seroprevalence levels, whereas the northern and northeastern regions, particularly Plateau and Borno, are recognized as hotspots for HEV transmission [61]. These regional disparities are largely attributed to variations in water quality, sanitation infrastructure, and population displacement patterns. Outbreak-prone northern areas often experience seasonal flooding and conflict-related displacement, which further compromise safe water access and hygiene practices, creating ideal conditions for HEV persistence and spread [58] (Table 2a).

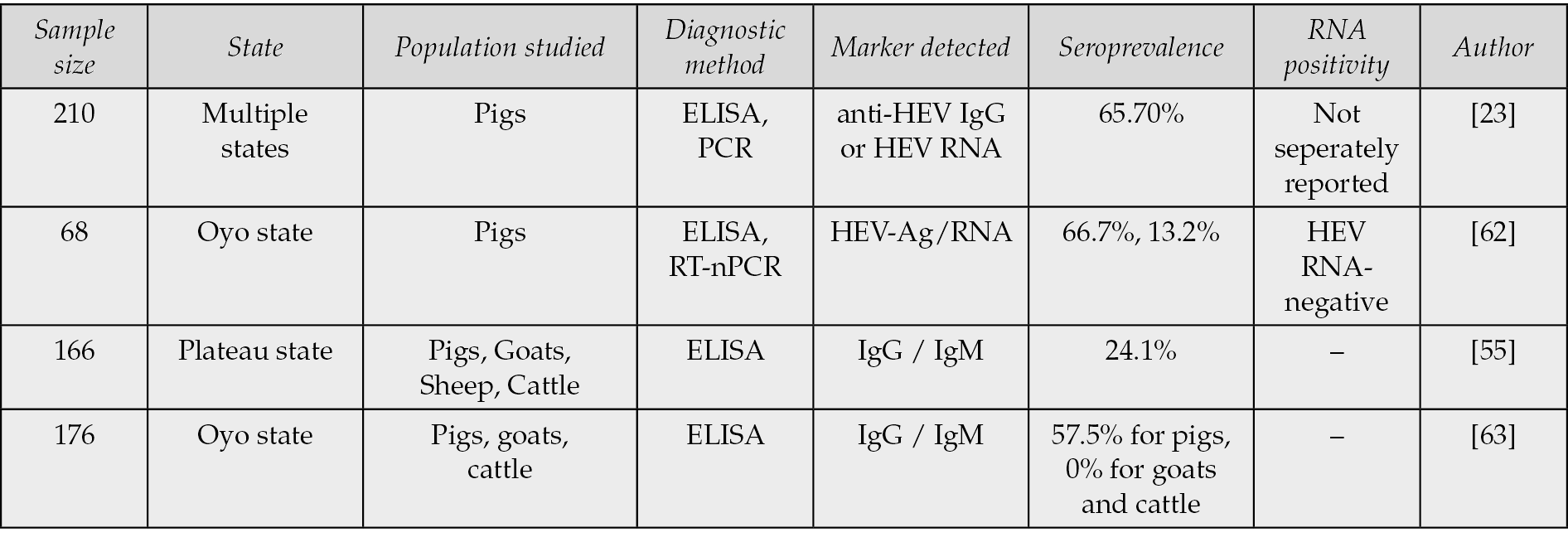

Zoonotic implications

Multiple studies provide evidence of the significant zoonotic role of pigs in the epidemiology of HEV in Nigeria. The review by Okagbue et al. (2019) reported a notably high seroprevalence of 65.7% in pigs, emphasizing their importance as a primary reservoir for HEV transmission [23]. Similarly, Junaid et al. (2014) documented a 24.1% seroprevalence across pigs, goats, sheep, and cattle, indicating that multiple livestock species may harbor the virus, albeit at varying levels of susceptibility [55]. In contrast, Antia et al. (2018) reported a 57.5% seroprevalence in pigs but found no evidence of infection in goats or cattle, suggesting a degree of host specificity in HEV circulation. Further supporting these observations, Olayinka et al. (2020) detected a 66.7% seroprevalence in pigs, reinforcing their epidemiological significance in the Nigerian context (Table 2b).

Table 2b - Animal HEV seroprevalence and diagnostic methods in Nigeria.

Comparative Insights: Nigeria vs Other African Countries

When examined within the broader African context, Nigeria’s HEV sero-epidemiological profile shows both similarities and differences compared to patterns observed elsewhere on the continent. The human seroprevalence in Nigeria (10-15%) is moderate relative to the extremely high rates reported in Egypt (50-80%), but it is still noticeably higher than those recorded in Tanzania (0.2-6%), highlighting the diverse nature of HEV exposure across Africa. In contrast, animal seroprevalence levels in Nigeria, particularly among pigs (30-65%), rank among the highest in Africa and are comparable to those from Ghana and Madagascar, thereby emphasizing the prominent role of animal reservoirs in maintaining viral circulation. Moreover, the occupational exposure patterns documented among butchers, pig handlers, and livestock owners mirror those observed in Ghana and Cameroon, suggesting a shared West and Central African risk profile shaped by similar farming systems, hygiene practices, and animal-human interfaces [37]. Collectively, these comparisons position Nigeria in a regional continuum of HEV transmission and underscore the need for integrated surveillance strategies and cross-border approaches to mitigate HEV transmission in both human and animal populations effectively.

RECOMMENDATIONS: A CALL FOR A ONE HEALTH APPROACH

Human-Animal-Environment Interface

Collaboration between disciplines is crucial for implementing prevention and control measures that benefit public health, veterinary health, and the physical environment [64]. Various high-risk practices, knowledge gaps, and misconceptions about HEV have been shown to exist among occupationally exposed groups in slaughterhouses, including slaughterhouse workers, butchers, veterinarians, and livestock handlers [51, 65]. This group needs to be examined qualitatively and quantitatively for socio-cultural and workplace factors that influence the adoption of preventive measures, such as using PPE such as boots, gloves, overalls, rubber gloves and eye shield in their respective populations [66, 67]. Further analysis of the main epidemiological factors triggering HEV-induced hepatitis should be conducted to understand how the season and climatic conditions of the environment strengthen or reduce the factors contributing to the transmission of viral pathogens in the most susceptible species, including humans [56]. Understanding this interface is crucial for effective disease management [68].

Integration of Epidemiological Data

Combining human health data and case reports of suspected and confirmed cases of HEV-induced hepatitis with veterinary reports from local slaughterhouses and abattoirs, as well as environmental data on weather forecasts, climatic changes, and other competing environmental hazards, contributes to a comprehensive analysis of HEV transmission dynamics [69]; further, supporting the identification and integration of sources of infection and the assessment of risk factors. Veterinary and genomic sciences have played a critical role in disease epidemiology, with veterinary sciences focusing on screening animals while genomics elucidates genetic factors that influence susceptibility and transmission [70]. To integrate the epidemiological trend line, the veterinary and genomic approaches must be combined to monitor the trend line of disease prevalence and incidence. A holistic approach that would lead to more effective control measures.

Animal Screening as a Key Component

of the One Health Framework

Livestock and domestic animals should be monitored and tested, particularly those located in areas where HEV has been previously reported [71]. Surveillance and screening techniques should include routine clinical examination and targeted screening, the use of diagnostic methods such as Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and furthermore the conduction of risk-based assessment in high-risk areas or farms with known outbreaks [72, 73]. Additionally, evidence-based case studies, particularly in countries with extensive swine industries, regions with high swine populations, such as Nigeria, can also help prevent transmission of infected pigs or offal to humans through undercooked pork [74].

Community and Veterinary Rural and Urban Extension Services

A Veterinary Medicine and Agriculture Advisory Committee should be established and adequately utilized by the government and research institutions [10, 75]. Research has shown that average farmers need to be more educated, especially in developing countries like Nigeria, and it is essential to ensure that they are adequately informed about the research findings [64, 76]. Rural extension services that understand, interpret, translate, and disseminate research findings to rural and local farmers in diverse communities are essential in combating hepatitis caused by HEV and preventing future increases in viral pathogenesis affecting the population [77]. It is crucial to involve farmers and veterinarians in HEV surveillance and control measures. Education about proper animal care and hygiene practices can reduce the risk of HEV transmission.

Monitoring and surveillance

The persistence and spread of HEV in Nigeria result from a combination of environmental, socioeconomic, and infrastructural challenges. Climatic conditions, seasonal flooding, and inadequate water management frequently contaminate drinking sources, while poor sanitation infrastructure in overcrowded urban centers further drives transmission [35, 78]. Compounding these issues are poverty, low educational attainment, and limited access to healthcare, all of which sustain the high prevalence of HEV [78]. Addressing these drivers requires a holistic and multi-layered response. A national strategy should prioritize the development of robust surveillance systems capable of integrating clinical, environmental, and veterinary data [75]. Such systems would enable timely detection of outbreaks and support evidence-based interventions. Parallel to this, hygiene and preventive practices – including boiling water, hand washing, and proper cooking of meat – must be promoted through sustained public health campaigns. Community education and engagement are critical to ensure these practices become part of everyday routines [79].

Policy and regulatory actions

Policy and regulatory actions should target food safety and environmental hygiene, with governments and health authorities ensuring routine inspection of animals, as well as systematic pre- and post-slaughter data collection in abattoirs [80]. These measures, combined with stronger food safety enforcement, will reduce zoonotic transmission risks. Community-based initiatives that empower local populations to understand HEV risks and adopt preventive measures can further enhance compliance and long-term control [80]. Future directions should include advancing diagnostic capacity, making tools more accessible for both human and animal screening. Genomic research offers an additional frontier, with the potential to uncover genetic determinants of susceptibility and transmission that could inform targeted interventions [70, 80]. Finally, combating HEV effectively will require strong international collaboration, partnerships among governments, global health authorities, and research institutions are vital for sharing best practices, harmonizing control measures, and strengthening collective resilience against HEV [12, 80].

Limitations

We acknowledge the limitations inherent in this review methodology. Firstly, dependence on published studies excludes unpublished surveillance data, potentially leading to an underestimation of the actual HEV burden. Secondly, inconsistencies in diagnostic methods (ELISA, PCR, rapid immunoassays) and heterogeneity in study designs across studies hinder comparability and limit the applicability of uniform quality-scoring tools. Thirdly, Nigeria-specific data remain limited, with most studies focusing on states, thereby limiting the ability to generalize findings to the entire nation. Notwithstanding these limitations, triangulating evidence from multiple sources has enabled us to delineate epidemiological trends and principal challenges pertinent to policy development and One Health interventions.

CONCLUSIONS

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) remains a neglected yet significant cause of acute viral hepatitis in Nigeria and across Africa [1, 10]. Although sporadic outbreaks have drawn attention to its public health relevance, the true burden of HEV infection is likely underestimated due to limited surveillance, inconsistent diagnostic capacity, and widespread underreporting [12]. HEV transmission is sustained not only through contaminated water sources but also amplified by zoonotic reservoirs, particularly pigs [46, 58, 61].

Vulnerable populations – including pregnant women, HIV-infected individuals, and livestock handlers – remain at heightened risk of infection and severe outcomes, reflecting both clinical vulnerability and occupational exposure [56, 81, 82].

Nigeria highlights the multidimensional nature of HEV epidemiology, where environmental, behavioral, and zoonotic factors intersect, but its experience reflects broader continental trends. The various yet interrelated epidemiological patterns across Africa show both the magnitude of the HEV problem and the critical need for coordinated regional intervention. Improving surveillance, diagnostic capacity, and intersectoral coordination within a continent-wide One Health framework will be critical in reducing the impact of this neglected virus and preventing future outbreaks.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the manuscript equally.

REFERENCES

[1] Aslan AT, Balaban HY. Hepatitis E virus: Epidemiology, diagnosis, clinical manifestations, and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2020; 26(37): 5543.

[2] Panda SK, Thakral D, Rehman S. Hepatitis E virus. Rev Med Virol. 2007; 17(3): 151-180.

[3] Purcell RH, Emerson SU. Hepatitis E: an emerging awareness of an old disease. J Hepatol. 2008; 48(3): 494-503.

[4] Patra S, Kumar A, Trivedi SS, et al. Maternal and fetal outcomes in pregnant women with acute hepatitis E virus infection. Ann Intern Med. 2007; 3;147(1): 28-33.

[5] Girish V, Grant LM, Sharma B, et al. Hepatitis E. [Updated 2025 Apr 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532278/.

[6] Wang B, Meng XJ. Structural and molecular biology of hepatitis E virus. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021; 19: 1907-1916.

[7] Yamashita T, Mori Y, Miyazaki N, et al. Biological and immunological characteristics of hepatitis E virus-like particles based on the crystal structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009; 106(31): 12986-12991.

[8] Haase JA, Schlienkamp S, Ring JJ, et al. Transmission patterns of hepatitis E virus. Curr Opin Virol. 2025; 70: 101451.

[9] Singson S, Shastry S, Sudheesh N, et al. Assessment of Hepatitis E virus transmission risks: a comprehensive review of cases among blood transfusion recipients and blood donors. Infect Ecol Epidemiol. 2024; 14(1): 2406834.

[10] Boadella M, Casas M, Martín M, et al. Increasing contact with hepatitis E virus in red deer, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16(12): 1994-1996.

[11] Saade MC, Haddad G, Hayek M, et al. The burden of Hepatitis E virus in the Middle East and North Africa region: a systematic review. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2022; 16(05): 737-744.

[12] Boukhrissa H, Mechakra S, Mahnane A, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus among blood donors in eastern Algeria. Tropical Doctor. 2022; 52(4): 479-483.

[13] Long F, Yu W, Yang C, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis E virus infection in goats. J Med Virol. 2017; 89(11): 1981-1987.

[14] Huang F, Li Y, Yu W, et al. Excretion of infectious hepatitis E virus into milk in cows imposes high risks of zoonosis. Hepatology. 2016; 64(2): 350-359.

[15] Mirzaev UK, Yoshinaga Y, Baynazarov M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of hepatitis E virus antibody tests: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Hepatol Res. 2025; 55(3): 346-62.

[16] Covarrubias N, Hurtado C, Díaz A, et al. Hepatitis E virus seroprevalence: a reappraisal. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2015; 32(4): 482-484.

[17] Kodani M, Kamili NA, Tejada-Strop A, et al. Variability in the performance characteristics of IgG anti-HEV assays and its impact on reliability of seroprevalence rates of hepatitis E. J Med Virol. 2017; 89(6): 1055-1061.

[18] Ekanem E, Ikobah J, Okpara H, et al. Seroprevalence and predictors of hepatitis E infection in Nigerian children. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015; 9(11): 1220-1225.

[19] Tucker TJ, Kirsch RE, Louw SJ, et al. Hepatitis E in South Africa: Evidence for sporadic spread and increased seroprevalence in rural areas. J Med Virol.1996; 50(2): 117-119.

[20] Kim JH, Nelson KE, Panzner U, et al. A systematic review of the epidemiology of hepatitis E virus in Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2014; 14(1); 1-13.

[21] Bagulo H, Majekodunmi AO, Welburn SC. Hepatitis E in Sub Saharan Africa - A significant emerging disease. One Health. 2020; 11: 100186.

[22] Elduma AH, Zein MMA, Karlsson M, et al. A Single Lineage of Hepatitis E Virus Causes Both Outbreaks and Sporadic Hepatitis in Sudan. Viruses. 2016; 8: 10.

[23] Okagbue HI, Adamu MO, Bishop SA, et al. Hepatitis E infection in Nigeria: a systematic review. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019; 7(10): 1719-1722.

[24] Caron M, Kazanji M. Hepatitis E virus is highly prevalent among pregnant women in Gabon, central Africa, with different patterns between rural and urban areas. Virol J. 2008; 14: 158.

[25] Richard-Lenoble D, Traore O, Kombila M, et al. Hepatitis B, C, D, and E markers in rural equatorial African villages (Gabon). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995; 53(4): 338-341.

[26] Feldt T, Sarfo FS, Zoufaly A, et al. Hepatitis E virus infections in HIV-infected patients in Ghana and Cameroon. J Clin Virol. 2013; 14: 18-23.

[27] Pawlotsky JM, Belec L, Gresenguet G, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis B, C, and E markers in young sexually active adults from the Central African Republic. J Med Virol. 1995; 14: 269-272.

[28] Modiyinji AF, Amougou Atsama M, Monamele Chavely G, et al. Detection of hepatitis E virus antibodies among Cercopithecidae and Hominidae monkeys in Cameroon. J Med Primatol. 2019; 48(6): 364-366.

[29] Gambel JM, Drabick JJ, Seriwatana J, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus among United Nations Mission in Haiti (UNMIH) peacekeepers, 1995. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998; 58(6): 731-736.

[30] Stark K, Poggensee G, Hohne M, et al. Seroepidemiology of TT virus, GBC-C/HGV, and hepatitis viruses B, C, and E among women in a rural area of Tanzania. J Med Virol. 2000; 14: 524-530.

[31] Ben Halima M, Arrouji Z, Slim A, et al. Epidemiology of hepatitis E in Tunisia. Tunis Med. 1998; 14: 129-131.

[32] Darwish MA, Faris R, Clemens JD, et al. High seroprevalence of hepatitis A, B, C, and E viruses in residents in an Egyptian village in The Nile Delta: a pilot study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996; 54(6): 554-558.

[33] Fix AD, Abdel-Hamid M, Purcell RH, et al. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis E in two rural Egyptian communities. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000; 14: 519-523.

[34] Abe K, Li TC, Ding X, et al. International collaborative survey on epidemiology of hepatitis E virus in 11 countries. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006; 14: 90-95.

[35] Stoszek SK, Abdel-Hamid M, Saleh DA, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis E antibodies in pregnant Egyptian women. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006; 14: 95-101.

[36] Gad YZ, Mousa N, Shams M, et al. Seroprevalence of subclinical HEV infection in asymptomatic, apparently healthy, pregnant women in Dakahlya Governorate, Egypt. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2011; 5(2): 136-39.

[37] Aamoum A, Baghad N, Boutayeb H, et al. Séroprévalence de l’hépatite E a Casablanca Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus in Casablanca. Med Mal Infect. 2004; 34(10): 49192.

[38] Bernal MC, Leyva A, Garcia F. Seroepidemiological study of hepatitis E virus in different population groups. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995; 14: 954-958.

[39] Temmam S, Besnard L, Andriamandimby SF, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis E in humans and pigs and evidence of genotype-3 virus in swine, Madagascar. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013; 88(2): 329-338.

[40] Hannachi N, Boughammoura L, Marzouk M, et al. Viral infection risk in polytransfused adults: seroprevalence of seven viruses in central Tunisia. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2011; 14: 220-225.

[41] Rezig D, Ouneissa R, Mhiri L, et al. Seroprevalences of hepatitis A and E infections in Tunisia. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2008; 14: 148-153.

[42] Jacobs C, Chiluba C, Phiri C, et al. Seroepidemiology of Hepatitis E Virus Infection in an Urban Population in Zambia. Strong Association with HIV and Environmental Enteropathy J Infect Dis. 2014; 14: 652-627.

[43] Aubry P, Niel L, Niyongabo T, et al. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis E Virus in an Adult Urban Population from Burundi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997; 57(3): 272-273.

[44] Martinson FE, Marfo VY, Degraaf J. Hepatitis E virus seroprevalence in children living in rural Ghana. West Afr J Med. 1999; 14: 76-9.

[45] Bagulo H, Majekodunmi AO, Welburn SC. Hepatitis E seroprevalence and risk factors in humans and pig in Ghana. BMC Infect Dis. 2022; 22: 132.

[46] Osundare FA, Klink P, Akanbi OA, et al. Hepatitis E virus infection in high-risk populations in Osun State, Nigeria. One Health. 2021; 13:100256.

[47] Grabow WO, Favorov MO, Khudyakova NS, et al. Hepatitis E seroprevalence in selected individuals in South Africa. J Med Virol. 1994; 14: 384-388.

[48] Amer AF, Zaki SA, Nagati AM, et al. Hepatitis E antibodies in Egyptian adolescent females: their prevalence and possible relevance. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 1996; 14: 273-284.

[49] Adjei AA, Aviyase JT, Tettey Y, et al. Hepatitis E virus infection among pig handlers in Accra, Ghana. East Afr Med J. 2009; 86(8): 359-363.

[50] Meldal BH, Sarkodie F, Owusu-Ofori S, et al. Hepatitis E virus infection in Ghanaian blood donors – the importance of immunoassay selection and confirmation. Vox Sang. 2012; 14: 30-36.

[51] Hannachi N, Hidar S, Harrabi I, et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors of hepatitis E among pregnant women in central Tunisia. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2011; 14: e115-e118.

[52] Traoré KA. Seroprevalence of Fecal-Oral Transmitted Hepatitis a and E Virus Antibodies in Burkina Faso. PLoS One. 2012; 7(10): 48125.

[53] Temmam S, Besnard L, Andriamandimby SF, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis E in humans and pigs and evidence of genotype-3 virus in Swine, Madagascar. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2013; 88(2): 329-338.

[54] Oluremi AS, Casares-Jimenez M, Opaleye OO, et al. Butchering activity is the main risk factor for hepatitis E virus (Paslahepevirus balayani) infection in southwestern Nigeria: a prospective cohort study. Front Microbiol. 2023; 14: 1247467.

[55] Junaid SA, Agina SE, Jaiye K. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis E Virus among Domestic Animals in Plateau State–Nigeria. Microbiol Res J Int. 2014; 4(8): 924-934.

[56] Webb GW, Dalton HR. Hepatitis E: an underestimated emerging threat. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2019; 6: 1-18.

[57] Osundare FA, Klink P, Majer C, et al. Hepatitis E Virus Seroprevalence and Associated Risk Factors in Apparently Healthy Individuals from Osun State, Nigeria. Pathogens. 2020; 9(5): 392.

[58] Ashipala DO, Tomas N, Joel MH. Hepatitis E: Overview and Management in Namibia. In book: Epidemiological Research Applications for Public Health Measurement and Intervention. 2021; 144-156. doi:10.4018/978-1-7998-4414-3.ch009.

[59] Labrique AB, Sikder SS, Krain LJ, et al. Hepatitis E, a vaccine-preventable cause of maternal deaths. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012; 18(9): 1401-1404.

[60] Oluremi AS, Opaleye OO, Ogbolu DO, et al. High Viral Hepatitis Infection among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinic in Adeoyo Maternity Teaching Hospital Ibadan (AMTHI) Oyo State, Nigeria. J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2020; 41(5): 913-923.

[61] Abioye JOK, Anarado KS, Babatunde S. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among students of Bingham University, Karu in North-Central Nigeria. Int J Pathog Res. 2021; 7(4): 38-47.

[62] Olayinka A, Ifeorah IM, Omotosho O, et al. A possible risk of environmental exposure to HEV in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2020; 41(5): 875-884.

[63] Antia RE, Adekola AA, Jubril AJ, et al. Hepatitis E virus infection seroprevalence and the associated risk factors in animals raised in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2018; 39(5): 509-520.

[64] Eussen BG, Schaveling J, Dragt MJ. Stimulating collaboration between human and veterinary health care professionals. BMC Vet Res. 2017; 13: 174.

[65] Rajendiran S, Li Ping W, Veloo Y, et al. Awareness, knowledge, disease prevention practices, and immunization attitude of hepatitis E virus among food handlers in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2024; 20(1): 2318133.

[66] Ayoola MC, Akinseye VO, Cadmus E, et al. Prevalence of bovine brucellosis in slaughtered cattle and barriers to better protection of abattoir workers in Ibadan, South-Western Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2017; 28: 68.

[67] George J, Shafqat N, Verma R, et al. Factors influencing compliance with Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) use among healthcare workers Cureus. 2023; 15(2): 35269.

[68] Lu L, Wu J. Hepatitis E Virus Transmission and Its Interactions with the Host. Microorganisms. 2020; 8(6): 960.

[69] Paltiel AD, Zheng A, Zheng A. Investing in Community Health: The Impact of Continuous Funding on Disease Management. Am J Public Health. 2022; 112(3): 431-439.

[70] Raimondo M. Molecular Detection of Hepatitis E Virus in Pigs: A Review of Current Techniques. Vet Microbiol. 2021; 252: 108965.

[71] Kenney SP. The Current Host Range of Hepatitis E Viruses. Viruses. 2019; 11(5): 452.

[72] Talapko J, Meštrović T, Pustijanac E, et al. Towards the Improved Accuracy of Hepatitis E Diagnosis in Vulnerable and Target Groups: A Global Perspective on the Current State of Knowledge and the Implications for Practice. Healthcare (Basel). 2021; 9(2): 133.

[73] Dubbert T, Meester M, Smith RP, et al. Biosecurity measures to control hepatitis E virus on European pig farms. Front Vet Sci. 2024; 11: 1328284.

[74] Augustyniak A, Pomorska-Mól M. An Update in Knowledge of Pigs as the Source of Zoonotic Pathogens. Animals. 2023; 13(20): 3281.

[75] Mohr BJ, Souilem O, Fahmy SR. Guidelines for the establishment and functioning of Animal Ethics Commitees (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees) in Africa. Lab Anim. 2024; 58(1): 82-92.

[76] Pawlak K, Kołodziejczak M. The Role of Agriculture in Ensuring Food Security in Developing Countries: Considerations in the Context of the Problem of Sustainable Food Production. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13): 5488.

[77] Danso-Abbeam G, Ehiakpor DS, Aidoo R. Agricultural extension and its effects on farm productivity and income: insight from Northern Ghana. Agric & Food Secur. 2018; 7: 74.

[78] Raji YE, Toung OP, Taib NM, et al. Hepatitis E Virus: An emerging enigmatic and underestimated pathogen. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022; 29(1): 499-512.

[79] Njoga EO, Ilo SU, Nwobi OC, et al. Pre-slaughter, slaughter and post-slaughter practices of slaughterhouse workers in Southeast, Nigeria: Animal welfare, meat quality, food safety and public health implications. PLoS One. 2023; 18(3): 0282418.

[80] Zhang XX. J, YZ. L, H Y. Infectious disease control: from health security strengthening to health systems improvement at global level. glob health res policy. 2023; 8: 38.

[81] Pérez-Gracia MT, García M, Suay B, et al. Current Knowledge on Hepatitis E. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2015; 3(2): 117-126.

[82] Maehira Y, Spencer RC. Harmonization of Biosafety and Biosecurity Standards for High-Containment Facilities in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: An Approach from the Perspective of Occupational Safety and Health. Front Public Health. 2019; 7: 249.