Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 4, 461-474, 2025

doi: 10.53854/liim-3304-12

INFECTIONS IN THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE

From Black Death to COVID-19: Lessons Learned from the Past Pandemics

Sina Radparvar

Department of Internal Medicine, Southern California Permanente Medical Group, 13652 Cantara Street, Panorama City, California, 91402 USA.

Article received 16 December 2024 and accepted 3 November 2025

Corresponding author

Sina Radparvar

E-mail: sina.radparvar@gmail.com

SUMMARY

Introduction: Throughout human history, pandemics such as Black Death, Smallpox, Spanish Flu and COVID-19 caused global outbreaks and spread of infectious pathogens resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. They also had profound social, cultural, political and economic effects. Various public health containment measures and treatment strategies were implemented in response to the outbreaks. Societal responses to the pandemics and the recommended control measures, though variable, followed common central themes over the centuries. Some of common themes included blaming outsiders or marginalized communities for the spread of diseases, defiance of public health measures, demands for change through social unrest, the spread of misinformation about diseases and unproven treatments, and complaints about healthcare disparities and socioeconomic inequalities.

Methods: Literature reviews were conducted via academic search engines Medline, Google Scholar, Web of Science and to identify pertinent historical and modern research and review articles related to the topic.

Results: The paper reviews the historical significance of the four pandemics, their pathophysiology, the public health strategies against the infectious agents and the psychosocial impacts of the outbreaks. The findings suggest that successful response to pandemic recurrences is not only driven by scientific advancements and government mandates but is also dependent on societal behavior and reactions as well as community environments and social determinants of health.

Discussion: Throughout previous pandemics, valuable lessons were overlooked, and little attention was placed on psychosocial factors. Understanding societal behaviors, human nature, disparities in socioeconomic status and inequalities can have a profound impact in combating the next pandemic.

Keywords: Black Death, Smallpox, Spanish flu, COVID-19, pandemic.

INTRODUCTION

Over the centuries, infectious diseases have been a significant cause of illness and death in human history. The shift from hunter-gatherer societies to agrarian communities resulted in birth of agriculture and livestock farming, which increased the transmission of zoonotic pathogens [1]. The spread of infectious diseases was further facilitated by colonization, slavery, war, trade and travel between communities [2, 3]. Following the industrial revolution, overcrowding and congestion in the cities had a negative impact on ecosystems and facilitated the emergence and spread of infectious diseases leading to outbreaks such as epidemics and pandemics [2].

Acting through invisible agents such as viruses, bacteria, and parasites, the infectious diseases have grappled communities as people have tried to make sense of the random destruction brought by the diseases. They affected physical well-being, mental health, relationships, social norms as well as economic and political policies.

Throughout the course of human history, outbreaks of Black Death, Smallpox, Spanish flu and COVID-19 were caused by the most notorious infectious diseases with spread across international borders defining them as pandemics. They caused significant morbidity and mortality as well as profound cultural, political and economic effects. The outbreaks also spurred scientific advancements in disease eradication including the discovery of germ theory of disease, understanding host-vector interactions, implementing case isolation and management systems, surveillance of pathogens at the human-animal-wildlife interface, genomic studies to track the spread of variants and follow epidemic dynamics, and development of novel antimicrobials and vaccines.

The advancement of science and medicine has revolutionized public health strategies in the fight against infectious diseases. Despite the evolution of these strategies, certain human behaviors and societal responses to pandemics have remained consistent throughout history. Recurrent social themes include scapegoating outsiders or marginalized communities for pandemics, spreading misinformation about the diseases and unproven treatments, resisting health care disparities and socioeconomic inequalities, advocating for change through social resistance, and defying public health measures such as social distancing, mask-wearing or vaccinations.

This publication aims to explore the history of four of the deadliest infectious diseases in human history: Black Death, Smallpox, Spanish Flu and COVID-19. It will analyze the pathophysiology of these infectious diseases, key strategies attempted to combat them, as well as the sociological aspects of illness, medicine and healthcare. The author seeks to analyze how these plagues impacted global health, the strategies governments implemented to address pandemic crises, and the societal responses and psychosocial themes that emerged during each outbreak.

The paper concludes that effective responses to pandemics are driven by advancements in science and medicine and government mandates, but also through community environments, social determinants of health and human behavior. Societal reactions influenced by human behavior and disparities in socioeconomic status, play a crucial role in combating future pandemics.

METHODOLOGY

Information for this narrative review was obtained from a comprehensive review of electronic medical literature databases using academic search engines Medline (via PubMed), Google Scholar, Web of Science and Scopus. The searches aimed to identify relevant original research, clinical studies, meta-analyses, and review articles in English from 1900 to 2024. Primary keyword such as “Black Death”, “Yersinia pestis”, “Smallpox”, “Spanish flu”, “Influenza”, “COVID-19”, “SARS-CoV-2” were combined with secondary keywords like “history”, “pandemic”, “public health interventions”, “control measures”, “societal behavior and response”, “treatments”, “social conflict”, “health inequalities” and “social unrest”.

The research focused on gaining a historical understanding of public health interventions, socioeconomic disparities, social responses, behaviors, and conflicts related to the four pandemics.

EVOLUTION OF PANDEMICS FROM MEDIEVAL TO MODERN TIMES

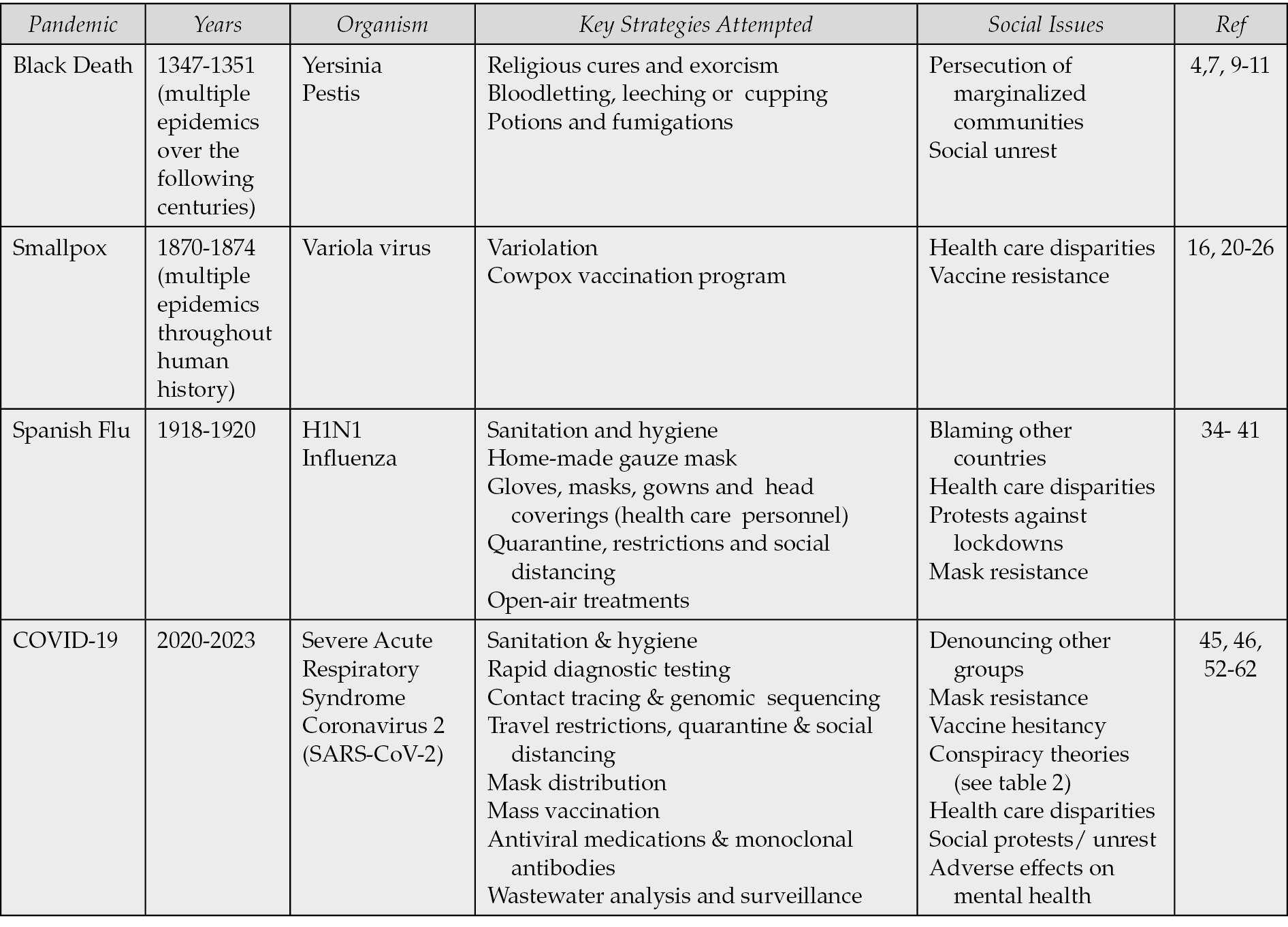

This section delves into the pathophysiology, control measures, and social implications of four significant pandemics throughout human history. These pandemics were carefully selected to illustrate the progression and influence of science, medicine, public health, as well as societal reactions over the past eight centuries. Table 1 provides an overview of the strategies devised to combat pandemics and the accompanying social issues from medieval to modern times.

Table 1 - Strategies to Counter Pandemics and Associated Social Issues from the Medieval to Modern Times.

Black Death

Black Death, also known as the bubonic plague, was a devastating infectious disease that swept through the world during the Middle Ages from 1347 to 1351 [4]. It decimated 30 to 50% of the European population in just four years, resulting in an estimated death toll of 200 million people worldwide [4]. The bubonic plague has continued to resurface in the form of epidemics since the Black Death, with the most recent epidemic reported in Madagascar from 1998 to 2016 [5].

Pathophysiology

Black Death was caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which is carried by fleas on rodents and then transmitted to humans through flea bites on the skin [4]. The bacterium can also spread between humans through contact or inhalation of aerosols [4]. After entering the host, Yersinia pestis evades the immune system and proliferates within macrophages [6]. Upon release from the macrophages, the bacterium triggers a pro-inflammatory response that leads to the onset of clinical symptoms [6].

Patients infected with the Yersinia pestis develop swollen and tender lymph glands, known as buboes, which turn black in color, giving the disease its name [7]. This phase, called bubonic plague, is the most common form of the disease and is characterized by symptoms such as fever, chills, headache, and weakness [8].

When the bacterium affects the lungs, a more severe form of the disease called pneumonic plague can occur, leading to symptoms such as coughing, hemoptysis, fever, and chest pain [6]. This form of plague can be spread through inhalation exposure [8].

The deadliest form of the Yersinia pestis is septicemic plague, which infects the bloodstream, causing hypotension, shock, ultimately resulting in 100% mortality [4, 6].

The high mortality rate of the Black Death pandemic was attributed to the lack of immunity among the population, as well as overcrowding and unsanitary living conditions in cities that facilitated the rapid spread of the Yersinia pestis bacteria by fleas [9].

Control Measures

The infectious agent responsible for the Black Death pandemic was not identified during the medieval period but was rather discovered in 1894 [7]. The medical knowledge in the Middle Ages was limited and heavily influenced by religious belief, folklore, herbalism, and superstition [7].

During this time, humeral or “miasma” theory served as the basis of medicine. The theory revolved around the idea that the Earth was composed of four elements: earth, water, fire and air [10]. Each element was associated with a bodily fluid (earth to black bile, water to phlegm, fire to yellow bile, and air to blood) [10].

Medieval physicians believed that Black Death was caused by an imbalance of bodily humors, which could be triggered by factors such as irregularity of seasons, astrologic events or inhalation of putrid fumes from decaying matter [10]. Treatments to correct the imbalance of humors included bloodletting, leeching and cupping [7, 10]. Plague doctors, summoned by the government to treat the sick, would often drain fluids from buboes, perform bloodletting, or prescribe medicines in an effort to balance bodily humors [7]. One popular remedy known as “the four thieves’ vinegar” contained garlic, meadowsweet, camphor, wormwood, cloves, marjoram, and sage, brewed in vinegar [4]. This remedy is believed to have had some efficacy against Yersinia pestis by acting as a flea repellent [4].

Social Issues

Blaming Others

During the pandemic, fear and confusion gripped the population, leading to a search for scapegoats. For centuries, Jews had been persecuted around the world and many Christians feared and resented Jews for their refusal to accept the Catholic Church [11]. This prevailing sentiment in Europe led to the widespread belief that Jews were responsible for poisoning water wells to spread disease among Christians [11]. Tragically, this unfounded accusation resulted in the massacre of thousands of Jews and the decimation of communities across the continent [11].

Social unrest

Fear and panic during the pandemic led to social disintegration, isolation, ostracism and breakdown of social bonds as people avoided the sick [9]. This phenomenon was particularly pronounced in the lower classes, who were already facing challenging social and economic circumstances [12]. Inequality and injustices exacerbated by to the pandemic sparked riots, social unrest, and revolt movements in various parts of the world [9].

The pervasive fear of illness and death permeated people’s lives as the pandemic claimed millions [13]. The Danse Macabre, also known as the Dance of Death, emerged as a powerful artistic representation of the coexistence of the living and the dead [13]. This artistic genre symbolized the inevitability of death, depicting a group of skeletons summoning individuals from different social classes to accompany a corpse to its final resting place [14].

As seen in Figure 1, the images illustrated protest against the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on the lower classes, showing individuals of various social statuses, from the pope to hermits, dancing alongside the skeletons [12]. The Dance of Death images gained popularity during the Middle Ages, appearing in churches and on cemetery walls [13]. Over the following centuries, these themes continued to inspire various forms of art, literature, and music [13].

Figure 1 - Danse Macabre (Dance of Death) Painting by Janez Kastva, 1490. Adopted from the replica of the original 15th century fresco in the Church of Holy Trinity, National Gallery of Slovenia, Ljubljana Slovenia. Public domain [15].

Impact and Lessons Learned

The Black Death pandemic had significant socioeconomic and political impacts on the medieval period, reshaping many aspects of life during that era. It brought forth harsh lessons about adversity, mortality, resilience, adaptability, inequality, social protest, and provoked major changes in social, political, and economic spheres. In Europe, the religious, cultural, political, and economic changes following the pandemic paved the way for the beginnings of the Renaissance and Reformation [9].

Smallpox

Smallpox, a viral infectious disease caused by the highly contagious airborne poxvirus known as variola virus, stands as one of the most devastating killers in human history, claiming up to 500 million lives in the 20th century alone [4]. The origins of the smallpox virus remain a mystery, although the discovery of typical eruptive macules on some Egyptian mummies suggests that it has plagued humanity for over 3000 years [4]. Like other pandemics, Smallpox spread across the globe in multiple outbreaks. The most infamous of these outbreaks, known as the “Great Pandemic of 1870-1875,” marked the final major smallpox pandemic [16]. Despite this, deadly smallpox epidemics continued to occur from the early sixteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, until the World Health Organization (WHO) launched a global eradication campaign in 1967 [4].

Pathophysiology

Humans are the sole known reservoir for the smallpox virus [17]. The virus is transmitted from person to person through contact with infected mucous membranes or by inhaling respiratory droplets [17]. Following inoculation, the virus infiltrates the oropharyngeal or respiratory mucosa and then spreads to the regional lymph nodes, causing viremia [17]. Eventually, the virus accumulates in the small vessels of the dermis, resulting in the characteristic macular eruption [17]. The rash may spread across the entire body and the cutaneous lesions progress from macular to papular, then to vesicular and finally to pustular form [17, 18]. Eventually, crusting and scabs develop that may result in scarring [17, 18].

Following an incubation period of 10-12 days, individuals may also experience a prodrome of fever, headache, malaise, and joint aches [17]. Complications of smallpox infection can include secondary skin infections, encephalitis, bronchopneumonia, osteomyelitis, orchitis, corneal ulcerations, and sepsis due to the inflammatory response, which can lead to shock and multiorgan failure [17, 18].

Control Measures

The battle against smallpox was a formidable challenge, with a mortality rate of 30% [19]. At that time, there were no specific treatments available, with prevention mainly relying on quarantine and social distancing measures. Smallpox was the first virus for which a successful vaccination was developed. However, the initial attempts at vaccination were met with controversy.

In the 18th century, a controversial vaccination method known as Variolation was introduced [20]. This procedure involved inoculating a small amount of virus from recovered patients into healthy individuals through inhalation or by scratching the material into the recipient’s arm [20]. While Variolation had a low mortality rate, it was ultimately ineffective as it did not prevent the spread of the virus to others, and sometimes even led to new outbreaks [20].

In 1796, Edward Jenner made a groundbreaking observation that milkmaids who had contracted cowpox were immune to smallpox [20]. He theorized that cowpox could be deliberately transmitted to the population to provide protection against smallpox [20]. After successfully inoculating a healthy patient with cowpox matter from a milkmaid’s sore, the patient developed a mild case of cowpox but ultimately recovered and gained immunity against smallpox [20].

Jenner’s revolutionary idea of vaccination with cowpox (vaccinia) instead of variolation, led to a significant decline in smallpox cases in the 19th century [20]. Despite its success, Jenner initially faced widespread criticism for his innovative approach [21].

Social Issues

Vaccine Misconceptions and Conspiracy Theories

The introduction of smallpox vaccination sparked fear and controversy, leading to a range of objections from various groups. Parents expressed concerns about subjecting their children to the procedure, while clergy members disapproved due to the vaccine’s animal origins [21]. Some individuals believed that vaccination infringed upon their personal freedoms [21].

Anti-vaccine conspiracy theorists took their objections to the extreme, warning that injecting “cow material” into the human body could result in individuals developing cow-like characteristics and experiencing bizarre mental effects and violent physical reactions, a phenomenon they termed “cow mania” [22].

Tensions escalated as governments began to implement mandatory vaccination policies. The British Compulsory Vaccination Act of 1853, which required smallpox vaccination for infants, was met with defiance and resistance, leading to violent protests and even imprisonment [23].

Similarly, in the United States, anti-vaccination mandates sparked protests and arrests [23]. However, the Supreme Court ultimately ruled in favor of mass vaccination, citing the threat that the disease posed to public safety [23].

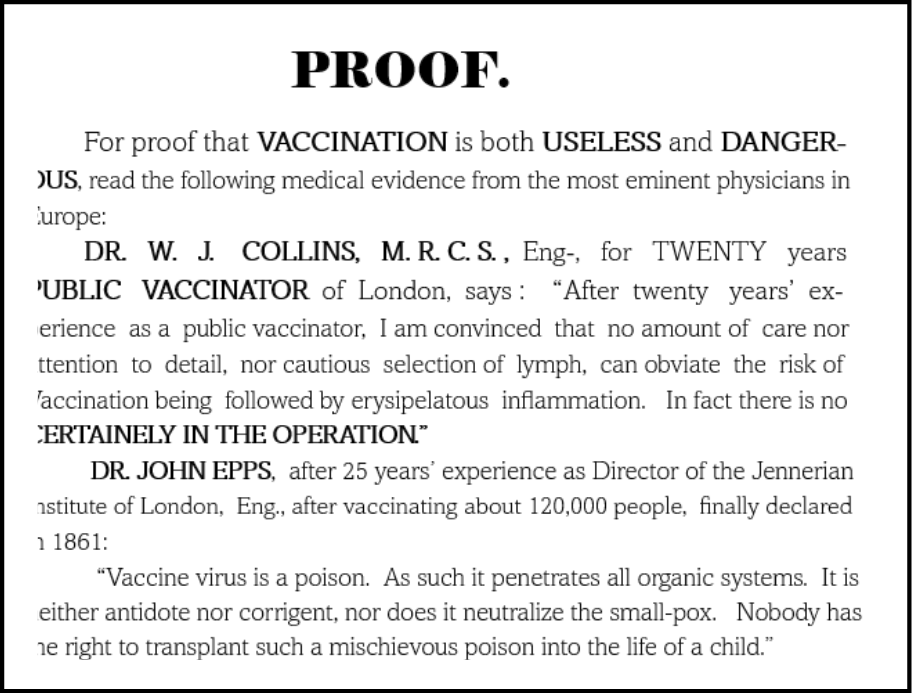

In Canada, Dr. Alexander Ross emerged as a prominent opponent of smallpox vaccination [24]. In 1885, he declared the vaccine to be poisonous, forming the Anti-Vaccination League as part of an international crusade against vaccination [24]. Ross published numerous anti-vaccination posters and pamphlets, including the infamous “Ross’ Pamphlet” [24]. The last section of this pamphlet which featured testimonials from prominent European experts is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2 - Excerpts from the Ross’ Pamphlet published in 1885. Adopted from the anti-smallpox vaccine pamphlet by Alexander M. Ross published amidst the 1885 smallpox epidemic in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Public domain [25].

Health Inequalities.

In comparison to other pandemics and epidemics, there has been a lack of in-depth studies examining the connection between smallpox and social disparities [26]. Recent research has revealed that, like other infectious diseases, smallpox had varying effects on different segments of the population based on health inequalities [26]. Not surprisingly, factors such as lower neighborhood wealth and higher housing density were associated with increased mortality rates from the virus, as well as lower rates of vaccination uptake [26].

Lessons from Smallpox

Smallpox is the first disease to have been eradicated although this was not achieved until more than 175 years after Edward Jenner’s assertion that the inoculation of cowpox virus could eliminate it from the earth [27]. Lessons learned from global smallpox vaccination included the importance of achieving community immunity by vaccinating at least 80% of the population, as well as development of monitoring systems for surveillance (case detection) and containment of outbreaks [27].

However, the pandemic also highlighted multiple social concerns surrounding eradication efforts, such as the rise of anti-vaccination movements and the disproportionate access to vaccination programs due to widespread health care inequities. Compulsory vaccination programs were implemented in a haphazard and discriminatory manner, leading to a lack of trust in governments during this time [28]. The history of vaccine misconceptions and conspiracy theories serves as a reminder of the complex interplay between science, public health, and individual beliefs.

Despite these obstacles, the 20th century saw a global vaccination campaign that ultimately led to the total eradication of smallpox, with the WHO declaring the world free of the disease in 1980 [27]. The significant events in this period, known as the “Progressive Era” [28], laid the foundations for today’s modern public health systems.

Spanish Flu

The 1918 influenza pandemic, also known as the Spanish flu, stands out as one of the most severe pandemics in the past century. This novel virus, which had no prior immunity, was incredibly effective in spreading from person to person on a global scale, particularly impacting young and healthy individuals [29]. The timing for the arrival of the influenza virus was ideal for rapid transmission, as new modes of mass transportation, such as railroads and supply ships, were expanding [30]. Additionally, the crowded living conditions in cities and military camps during World War I provided the perfect environment for the virus to thrive [30].

The Spanish flu pandemic infected an estimated 500 million people, roughly one-third of the world’s population, and resulted in the deaths of up to 100 million individuals worldwide over a span of two years [31].

Pathophysiology

The 1918 Spanish flu pandemic was caused by the H1N1 influenza virus, which contained genes of avian origin [32]. Unlike previous outbreaks, this strain had a devastating impact on young adults aged 20-40, as they lacked immunity to the viral components [32].

H1N1 influenza is typically transmitted through aerosol inhalation or droplet contact. Once the virus enters the body, it can cause inflammation in the upper respiratory passages, trachea, and lower respiratory tract [33]. The virus begins replicating within 48 hours of infection [33]. The infectious period starts a day before symptoms appear and can last for about 5 to 7 days after symptoms manifest [33].

Symptoms of H1N1 influenza can vary from mild to severe, with common signs including malaise, fever, muscle pain, runny nose, and cough [33]. These symptoms can persist for up to two weeks [33]. In severe cases, complications such as viral pneumonia, bacterial pneumonia, hemorrhagic bronchitis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) can occur, potentially leading to fatal outcomes [33, 34].

Control Measures

In 1918, the world was engulfed in war and was ill-prepared for the health crisis brought on by the influenza pandemic [35]. Various public health measures were put into place, including the use of facial coverings, strict sanitation protocols, quarantine, isolation, limits on public gatherings, social distancing, and the optimization of healthcare resources such as hospitals, nurses, and physicians [35].

During the time before antivirals and vaccines were available, open-air treatments gained popularity as a method of preventing and combating infectious diseases, particularly during the Spanish flu pandemic [34]. Temporary open-air tent hospitals were constructed, as it was believed that fresh air and sunlight could provide both social distancing and act as a natural disinfectant against the influenza virus [34].

Social Issues

Blaming Outsiders

The exact origin of the virus that caused the 1918 pandemic remains a topic of debate among historians. Research has revealed that Spain was an improbable source of the virus before its global spread [36]. The term “Spanish flu” was coined due to early reports from Spanish officials about a mysterious new illness in Madrid [36]. Interestingly, Spain later referred to the virus as the “French flu,” suggesting that it was brought to Madrid by French visitors [37]. This pattern of blaming outsiders for the spread of disease was common as in previous pandemics.

Resistance to Public Health Measures.

Public health measures implemented to combat the Spanish flu pandemic faced significant resistance in numerous countries. Criticism arose regarding the enforcement of mask mandates and the closure of public establishments such as businesses, schools, churches, and theaters [35]. Opposition groups emerged to protest the impact of these restrictions on businesses and social interactions, particularly within religious communities [35].

Many individuals underestimated the severity of the disease, dismissing it as “influenza hysteria” and suggesting that the resulting chaos and panic were more dangerous than the flu itself [38].

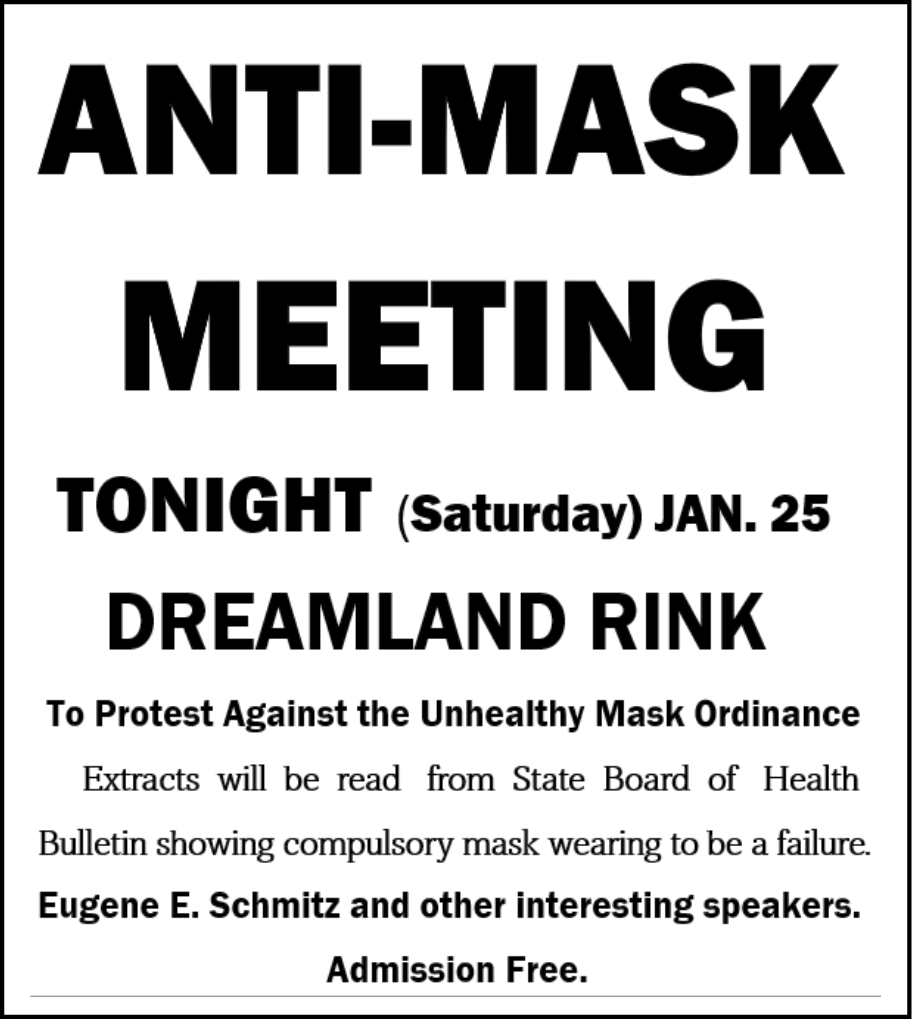

The use of face masks became a contentious issue, symbolizing a divide among different segments of the population [39]. Some believed that wearing a mask infringed upon their civil liberties, incited fear among the public, and represented weakness and a limitation of personal freedom [39]. Masks were mocked as “muzzles,” “germ shields,” and “dirt traps,” with protestors even going as far as cutting holes in them to smoke cigarettes [39]. The controversy surrounding facial coverings escalated into cultural rifts and political polarization [39]. In the United States, the formation of the Anti-Mask League sparked intense political activism [40].

Figure 3 illustrates a call to protest by the Anti-Mask League of San Francisco in 1919 by a newspaper advertisement.

Overall, the resistance to public health measures during the Spanish flu pandemic highlighted the complex intersection of public health, civil liberties, cultural beliefs, and political ideologies.

Figure 3 - Anti-Mask League Meeting Notice via Newspaper Advertisement. Adopted from San Francisco Chronicle Newspaper (January 25, 1919, p. 4). Public domain [41].

Pseudoscientific Agents.

During the 1918 influenza pandemic, medical treatments were scarce. The Influenza A virus was not identified until 1933 [42], leaving healthcare providers without diagnostic tools. Critical care support, mechanical ventilators, antiviral medications, vaccines, and antibiotics for secondary bacterial infections were all unavailable at the time [43].

Faced with the limitations of conventional medicine, many individuals turned to alternative or folk remedies [43]. Aspirin, a pain reliever used for centuries, became the go-to treatment for managing pain and fever during the flu outbreak [42, 43]. Other remedies included quinine for its antipyretic effects, salicin for its analgesic properties, cinnamon for its antipyretic qualities, and saline solution mouthwash [42, 43]. Unfortunately, none of these remedies were effective against the influenza virus.

Health Inequalities

Research has indicated that socioeconomic status significantly influenced the clinical outcomes of the influenza pandemic [44]. Various socioeconomic indicators, including unemployment, blue-collar occupation, lack of homeownership, lower income, and lower literacy levels, were associated with higher mortality rates [44]. The susceptibility to the influenza virus was heightened in impoverished communities characterized by overcrowded housing, inadequate sanitation services, and unsafe drinking water [45].

During World War I, numerous countries experienced a shortage of medical personnel due to doctors and nurses being deployed for military service [45]. Consequently, hospitals began turning away patients, particularly those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds [45].

Impact and Lessons learned

The influenza pandemic of 1918 highlighted numerous lessons and raised doubts about the effectiveness of public health measures in controlling communicable diseases [30]. Governments around the world quickly realized that implementing suggested measures such as bans on social gatherings, school closures, facial coverings, strict quarantine, isolation, and sanitation techniques was challenging due to public resistance in modern mass societies.

The painful lessons learned from the 1918 influenza pandemic and the social upheavals it caused were overshadowed by the events of World War I [31]. Unfortunately, the cultural legacy of the pandemic has been forgotten and overlooked in the teaching of history [31].

COVID-19

COVID-19, also known as coronavirus disease 2019, is a respiratory illness caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The emergence of this new pathogen was initially reported in November 2019 in Wuhan, China, and quickly spread globally [46]. By the spring of 2020, the pandemic had swept across the world, leaving a profound impact on economic, social, and political spheres. The pandemic affected over 768 million individuals, resulting in nearly 7 million deaths and an estimated economic loss of 16 trillion USD as of June 2023 [47].

Pathophysiology

SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted through small airborne aerosolized particles that can be inhaled, as well as larger respiratory droplets that can be spread through contact [48]. The infectious period begins 1-2 days before and up to 8-10 days after symptoms begin [49].

COVID-19 infections can present with a variety of clinical manifestations, ranging from asymptomatic infection to mild respiratory symptoms or severe critical respiratory illnesses that require hospitalization. Patients with underlying conditions, such as advanced age, obesity, diabetes, immunocompromising conditions, chronic kidney, heart or liver disease are at an increased risk of progressing to severe disease with complications [50]. The complications caused by inflammatory responses may include pneumonia, ARDS, encephalopathy, anosmia, rash, acute renal failure, thrombosis, and acute kidney injury, among others [51].

Control Measures

COVID-19 pandemic sparked unparalleled global reaction, leading to numerous countries implementing border closures, travel restrictions, and quarantine measures. In addition, there was rapid deployment of preventive measures and the development of diagnostic tools and treatments, such as antiviral medications, monoclonal antibodies and vaccines.

The pandemic placed immense pressure on healthcare systems, tested societal values and ethics as hospitals and healthcare workers grappled with shortages of essential resources like beds, ventilators, and personal protective equipment. Various public health strategies and treatment methods were swiftly developed to contain the spread of the virus, as outlined in Table 1.

Social Issues

Blaming outsiders

As seen in past pandemics, the tendency to scapegoat outsiders for the spread of disease appeared again. Following the identification of Wuhan, China as the epicenter of the outbreak, there were misguided efforts to attribute the disease to the ethnic origin of the Chinese population. This led to discriminatory treatment of Chinese individuals, including their expulsion from certain establishments [61].

Conspiracy Theories

In contrast to pandemics of the past, COVID-19 presented a unique global experience shared by people worldwide. The widespread use of digital technology and social media allowed individuals to connect and share their experiences, responses, and interpretations of the crisis, creating a new sense of reality.

However, the internet and social media also facilitated the spread of misinformation, leading to the circulation of false advice and conspiracy theories. This influx of unproven and potentially harmful remedies eroded public trust in scientifically proven solutions [63]. The term “misinfodemic” was coined to describe this phenomenon, which was exacerbated by the availability of online platforms [63].

Conspiracy theorists propagated beliefs that governments and organizations were using the pandemic to exert control over the population [64]. These beliefs fostered prejudice, distrust in science, and discouraged individuals from following public health guidelines and seeking lifesaving treatments [64].

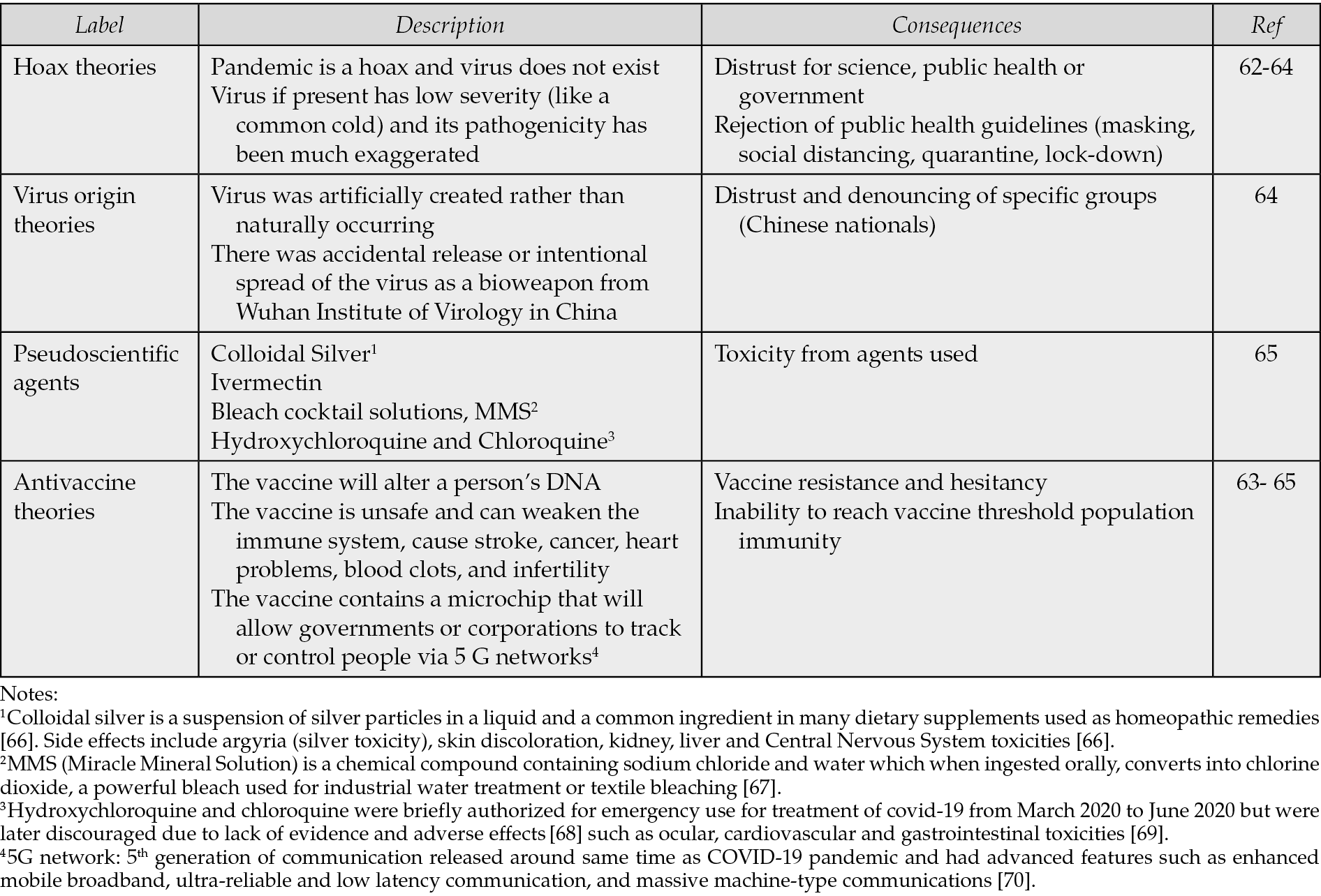

Table 2 outlines the major categories of misinformation and conspiracy theories surrounding COVID-19 and the consequences they had on pandemic management.

Table 2 - Main COVID-19 Categories of Misinformation and Conspiracy Theories and Potential Consequences.

Health Inequities.

Like previous pandemics, COVID-19 has highlighted long-standing systemic health and social disparities, as well as social determinants of health [62]. Individuals and groups with lower socioeconomic status were disproportionately affected [62]. For instance, those in the lower socioeconomic spectrum often worked in essential settings where remote work and physical distancing was not possible [62]. Additionally, they had a higher prevalence of untreated underlying conditions such as heart disease, hypertension, lung disease, obesity, or diabetes [62].

Social Unrest

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the surge in infections and fatalities within cities resulted in a decline in public health, economic downturn, and exacerbated social disparities [46]. Urban governments came under fire from the public for their handling of the health crisis and the resulting social and economic challenges [46].

The emotional strain, financial hardships, and heightened public discord eroded citizens’ confidence in government institutions, sparking social unrest and political demonstrations worldwide [46]. Protesters voiced demands for improved healthcare and social safety nets, increased economic aid, and an easing of restrictive measures like social distancing, mask mandates, and lockdowns [46].

Impact and Lessons Learned

The COVID-19 pandemic has been the most catastrophic infectious disease outbreak since the Spanish flu, causing profound global impact. This newly emerging infectious pathogen with pandemic potential proved to be difficult to control [62]. However, the rapid and aggressive development of public health interventions, therapeutics, and vaccine development were impressive achievements [62]. Additionally, the development of rapid viral genomic analysis allowed for tracking the spread of variants and understanding epidemic dynamics [54].

Despite these advancements, numerous societal issues and social reactions arose, echoing themes seen in previous pandemics. These included divergent impacts based on socioeconomic class, healthcare inequities, opposition to public health policies, conspiracy theories, and social unrest.

As with previous pandemics, the lessons learned were quickly forgotten once the WHO declared an end to the global health emergency for COVID-19 in May 2023.

DISCUSSION

Pandemics are complex events that have afflicted humanity from antiquity to the present. They have had profound influence in shaping public health systems, societal relations, economic and political policies.

Several factors have contributed to the increase in outbreaks of infectious agents in recent years. They include the growth of the global population, urbanization, encroachment into wildlife habitats, intensified farming practices, increased air travel, shifts in animal and insect distribution due to climate change, and a rise in mutations in RNA viruses [47].

Over course of history, treatment approaches for pandemics have undergone significant changes. From ancient practices such as exorcism and bloodletting during the Black Death pandemic to modern antivirals and monoclonal antibodies in the COVID-19 pandemic, the evolution of medical treatments has been remarkable. Similarly, dangerous techniques such as variolation used during smallpox pandemic were replaced with sophisticated mRNA vaccines used in the fight against COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the shift from open-air treatments used in Spanish Flu pandemic to airborne infection isolation and advanced respiratory support in COVID-19 pandemic, highlights the progress made in managing infectious diseases.

Despite the incredible advancements in technology, science, and medicine, as well as improvements in containment measures and treatment options for infectious diseases, pandemics tend to unfold in a similar dramatic fashion when it comes to social issues. The response of societies to these crises often follows comparable themes.

For instance, the Black Death pandemic highlighted the social class inequality, the smallpox pandemic saw the rise of anti-vaccine movements, the Spanish flu pandemic witnessed the formation of the Anti-Mask League, and the COVID-19 pandemic was marked by conspiracy theories and social unrest. These examples showcase the recurring themes of opposition and social resistance during pandemics.

When examining societal reactions to pandemics, other common themes emerge. These include ostracism, discrimination, scapegoating, government distrust, the search for miracle cures, conspiracy theories, mental health challenges, healthcare disparities, and restrictions on personal freedoms.

These patterns reveal that public responses to pandemics are not solely influenced by scientific evidence or government directives, but also by systemic healthcare disparities, individual beliefs, risk assessments, and personal autonomy. Neglecting the socioecological, sociopsychological, and socioeconomic factors that contribute to disease spread can result in poor compliance with public health measures, undermining global efforts to contain pandemics effectively.

Studying the history of past pandemics can offer valuable insights into the evolution of science, technology, medicine, as well as societal reactions, and cultural attitudes. By delving deeper into the complex cultural, psychosocial, and socioeconomic factors, we can better address public behaviors during crisis, thus minimizing the impact of future pandemics and facilitating a quicker return to normalcy.

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

[1] Okesanya OJ, Olatunji G, Manirambona E, et al. Synergistic fight against future pandemics: Lessons from previous pandemics. Infez Med. 2023; 31(4): 429-439. https://doi.org/10.53854/liim-3104-2.

[2] Piret J, Boivin G. Pandemics Throughout History. Front Microbiol. 2021; 11: 631736. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.631736.

[3] Baker RE, Mahmud AS, Miller IF, et al. Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022; 20: 193-205. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-021-00639-z.

[4] Garcia S. Pandemics and Traditional Plant-Based Remedies. A Historical-Botanical Review in the Era of COVID19. Front Plant Sci. 2020; 11: 571042. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.571042.

[5] Andrianaivoarimanana V, Piola P, Wagner DM, et al. Trends of Human Plague, Madagascar, 1998-2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019; 25(2): 220-228. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2502.171974.

[6] Dillard RL, Juergens, AL. Plague. StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2025. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31751045/ (accessed Sept 20, 2025).

[7] Mark JJ. Medieval Cures for the Black Death. World History Encyclopedia [Internet]. 2020. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1540/medieval-cures-for-the-black-death/ (accessed Sep 20, 2025).

[8] Signs and Symptoms of Plague. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/plague/signs-symptoms/index.html (accessed Oct 20, 2024).

[9] Zaidi SS. The Black Death Revisited: Lessons from the Bubonic Plague Pandemic of the Middle Ages. Medium. 2023. https://medium.com/@syedsharjeelshah11/the-black-death-revisited-lessons-from-the-bubonic-plague-pandemic-of-the-middle-ages-b4be09f98f2a (accessed Oct 20, 2024).

[10] Legan J. The medical response to the Black Death. Senior Honors Projects, 210-2019, James Madison University (JMU) Libraries Scholarly Commons. 2015. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019/103/ (accessed Oct 20, 2024).

[11] Zahler D. The Black Death. Minneapolis, USA, Twenty-First Century Books, 2009; p. 54-5.

[12] de Graaf B, Jensen L, Knoeff R, Santing C. Dancing with death. A historical perspective on coping with Covid-19. Risk Hazards Crisis. 2021; 12(3): 346-367. https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.12225.

[13] Lalitagod. The Dark History of Danse Macabre: Exploring the Epidemic Dance with Death. Medium. 2023. https://medium.com/@lalitagod100/the-dark-history-of-danse-macabre-exploring-the-epidemic-dance-with-death-fb0fe0cd686d (accessed Oct 19, 2024).

[14] Khan G, Parwez S. On societal response to pandemics: linking past experiences to present events. Discov Soc Sci Health. 2022; 2(10). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-022-00012-2.

[15] Kastav J. Dance of Death. Replica of 15th century fresco by Vladimir Macuk. Ljubljana: National Gallery of Slovenia. Wikimedia Commons. 1959. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dance_of_Death_(replica_of_15th_century_fresco;_National_Gallery_of_Slovenia).jpg (accessed Oct 20, 2024).

[16] O’Neill A. Smallpox death rate in select European countries during the Great Pandemic 1870-1875. Statista. 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1107752/smallpox-death-rate-great-pandemic-historical/ (accessed Oct 20, 2024).

[17] Tesini B. Smallpox (Variola) - Infectious Diseases. Merck Manual Professional Edition. 2025. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/pox-viruses/smallpox (accessed Oct 20, 2025).

[18] Smallpox. Iowa Health & Human Services. 2025. https://hhs.iowa.gov/center-acute-disease-epidemiology/epi-manual/reportable-diseases/smallpox (accessed Oct 20, 2025).

[19] Martini M, Bifulco M, Orsini D. Smallpox vaccination and vaccine hesitancy in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1801) and the great modernity of Ferdinand IV of Bourbon: a glimpse of the past in the era of the SARS-COV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. Public Health 2022; 213: 47-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.09.012.

[20] Riedel S. Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2005; 18(1): 21-5. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028.

[21] History of Anti-Vaccination Movements. History of vaccines. n.d. https://historyofvaccines.org/vaccines-101/misconceptions-about-vaccines/history-anti-vaccination-movements (accessed Oct, 2024).

[22] Mchugh J. The world’s first anti-vaccination movement spread fears of half-cow babies. The Seattle Times [Internet]. 2021, Nov 14. https://www.seattletimes.com/nation-world/the-worlds-first-anti-vaccination-movement-spread-fears-of-half-cow-babies/ (accessed Oct 20, 2024).

[23] Lane HC, Gordon SM. Vaccine hesitancy in the time of COVID: How to manage a public health threat. Cleve Clin J Med 2024; 91(9): 565-73. https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.91a.24062.

[24] Sholts S. The Bombastic 19th-Century Anti-Vaxxer Who Fueled Montreal’s Smallpox Epidemic. The MIT Press Reader. 2022. https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/the-bombastic-19th-century-anti-vaxxer-who-fueled-montreals-smallpox-epidemic/ (accessed Oct 20, 2024).

[25] Ross, AM. Smallpox vaccine pamphlet. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons. 1885. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File%3AAlexander_M._Ross_-_smallpox_vaccine_pamphlet.pdf&page=3 (accessed Oct 20, 2024).

[26] Muurling S, Riswick T, Buzasi K. The Last Nationwide Smallpox Epidemic in the Netherlands: Infectious Disease and Social Inequalities in Amsterdam, 1870-1872. Soc Sci Hist. 2023; 47(2): 189-216. https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2022.31.

[27] Henderson DA. Principles and lessons from the smallpox eradication programme. Bull World Health Organ. 1987; 65(4): 535-46. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2491023/.

[28] Bencks-Brandeis J. How smallpox changed the face of public health. Futurity. 2020. https://www.futurity.org/smallpox-covid-19-2355462/ (accessed Oct 20, 2024).

[29] Taubenberger JK., Hultin JV, Morens DM. Discovery and characterization of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus in historical context. Antivir Ther. 2007; 12(4 Pt B): 581-91. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2391305/.

[30] Tomes N. “Destroyer and Teacher”: Managing the Masses during the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic. Public Health Rep. 2010; 125(3 suppl): 48-62. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549101250S308.

[31] Goldstein JL. The Spanish 1918 Flu and the COVID-19 Disease: The Art of Remembering and Foreshadowing Pandemics. Cell. 2020; 183(2): 285-289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.030.

[32] Worobey M, Han G.-Z, Rambaut A. Genesis and pathogenesis of the 1918 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014; 111(22): 8107-8112. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1324197111.

[33] Jilani TN, Jamil RT, Nguyen AD, Siddiqui AH. H1N1 Influenza. StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing. 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513241/ (accessed Oct 28, 2024).

[34] Hobday RA, Cason JW. The Open-Air Treatment of Pandemic Influenza. Am J Public Health. 2009; 99 (Suppl 2): S236-42. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.134627.

[35] Ott M, Shaw SF, Danila RN, Lynfield R. Lessons Learned from the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota. Public Health Rep. 2007; 122(6): 803-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490712200612.

[36] Hoppe T. “Spanish Flu”: When Infectious Disease Names Blur Origins and Stigmatize Those Infected. Am J of Public Health. 2018; 108(11): 1462-1464. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304645.

[37] Shafer R. Spain hated being linked to the deadly 1918 flu pandemic. Trump’s ‘Chinese virus’ label echoes that. The Washington Post [Internet]. 2020, Mar 23. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/03/23/spanish-flu-chinese-virus-trump/ (accessed Oct 28, 2024).

[38] McCarthy G, Shore S, Ozdenerol E, Stewart A, Shaban-Nejad A, Schwartz DL. History Repeating—How Pandemics Collide with Health Disparities in the United States. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023; 10: 1455-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01331-5.

[39] Hauser C. The Mask Slackers of 1918. The New York Times [Internet]. 2020 Dec 10. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/03/us/mask-protests-1918.html (accessed Oct 28, 2024).

[40] Dolan B. Unmasking History: Who Was Behind the Anti-Mask League Protests During the 1918 Influenza Epidemic in San Francisco? Perspect Med Humat. 2020; 5(19): 1-23. https://doi.org/10.34947/M7QP4M.

[41] Anti-Mask League Meeting Notice [Advertisement]. San Francisco Chronicle. 1919, Jan 25: 4. https://www.newspapers.com/article/san-francisco-chronicle-1919-01-25-anti/49861061/ (accessed Oct 29, 2024).

[42] Bernstein LH. The History of Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology in the late 19th and 20th Century. Leaders in Pharmaceutical Business Intelligence Group, LLC. 2014. https://pharmaceuticalintelligence.com/2014/12/09/the-history-of-infectious-diseases-and-epidemiology-in-the-late-19th-and-20th-century/ (accessed Oct 29, 2024).

[43] Jester BJ, Uyeki TM, Patel A, Koonin L, Jernigan DB. 100 Years of Medical Countermeasures and Pandemic Influenza Preparedness. Am J Public Health. 2018; 108(11): 1469-72. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304586.

[44] Mamelund SE. 1918 pandemic morbidity: The first wave hits the poor, the second wave hits the rich. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2018; 12(3): 307-313. http://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12541.

[45] Roberts JD, Tehrani SO. Environments, Behaviors, and Inequalities: Reflecting on the Impacts of the Influenza and Coronavirus Pandemics in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(12): 4484. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124484.

[46] Garcia Chueca E, Teodoro F. Pandemic and social protests: cities as flashpoints in the COVID-19 era. CIDOB Notes Internacionals. 2022; 266: 1-7. https://doi.org/10.24241/NOTESINT.2022/266/EN.

[47] Chiu K H-Y, Sridhar S, Yuen KY. Preparation for the next pandemic: challenges in strengthening surveillance. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2023; 12(2): 2240441. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2023.2240441.

[48] Hunt MG, Chiarodit D, Tieu T, Baum J. Using core values and social influence to increase mask-wearing in non-compliant college students. Soc Sci Med. 2022; 314: 115446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115446.

[49] Cria G, Hall A. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), COVID-19. Yellow Book: Health Information for International Travel. 2025. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2024/infections-diseases/covid-19 (accessed Sep 29, 2025).

[50] Clinical Recommendations for Patients with Underlying Medical Conditions: COVID-19. Minnesota Department of Health. 2024. https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/coronavirus/hcp/conditions.html (accessed Nov 1, 2024).

[51] Brown RL, Benjamin L, Lunn MP, et al. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of neuroinflammation in covid-19. BMJ. 2023; 382: e073923. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-073923.

[52] Kusama T, Takeuchi K, Tamada Y, Kiuchi S, Osaka K, Tabuchi T. Compliance Trajectory and Patterns of COVID-19 Preventive Measures, Japan, 2020-2022. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023; 29(9): 1747-56. https://doi.org/10.3201/EID2909.221754.

[53] Hatami H, Qaderi S, Shah J, et al. COVID-19 National Pandemic Management Strategies and their Efficacies and Impacts on the Number of Secondary Cases and Prognosis. Int J Prev Med. 2023; 13(1): 100. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_464_20.

[54] Cunningham N, Hopkins S. Lessons identified for a future pandemic. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2023; 78(Suppl 2): ii43-ii49. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkad310.

[55] Filip R, Gheorghita Puscaselu R, Anchidin-Norocel L, Dimian M, Savage WK. Global Challenges to Public Health Care Systems during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of Pandemic Measures and Problems. J Pers Med. 2022; 12(8): 1295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12081295.

[56] Dong Y, Shamsuddin A, Campbell H, Theodoratou E. Current COVID-19 treatments: Rapid review of the literature. J Glob Health. 2021; 11: 10003. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.11.10003.

[57] Haider II, Tiwana F, Tahir SM. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Adult Mental Health. Pak J Med Sci. 2020; 36(COVID19-S4): S90-S94. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2756.

[58] Wu X, Shi L, Lu X, Li X, Ma L. Government dissemination of epidemic information as a policy instrument during COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Chinese cities. Cities. 2022; 125: 103658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103658.

[59] Asaduzzaman M., Khai TS, de Claro V, Zaman F. Global Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution: A Call for More Integrated Approaches to Address Inequities in Emerging Health Challenges. Challenges J Planet Health. 2023; 14(4): 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe14040045.

[60] About CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nwss/about.html (accessed Oct 22, 2025).

[61] Braga A, Cortes JP, Pritsivelis C, Martire L. Why is knowing the history of syphilis is critical, even during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Bras Doenças Sex Transm. 2021; 33: e3300005. https://doi.org/10.5327/DST-2177-8264-20213305.

[62] Fauci AS, Folkers GK. Pandemic Preparedness and Response: Lessons From COVID-19. J Infect Dis. 2023; 228(4): 422-5. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiad095.

[63] Apetrei C, Marx PA., Mellors JW, Pandrea I. The COVID misinfodemic: not new, never more lethal. Trends Microbiol. 2022; 30(10): 948-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2022.07.004.

[64] van Mulukom V, Pummerer LJ, Alper S, et al. Antecedents and consequences of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2022; 301: 114912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114912.

[65] Debunking myths about COVID-19. Mayo Clinic Health System. 2021. https://www.mayoclinichealthsystem.org/hometown-health/featured-topic/covid-19-vaccine-myths-debunked (accessed Nov 1, 2024).

[66] Colloidal Silver: What You Need to Know. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). 2023. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/colloidal-silver-what-you-need-to-know (accessed Nov 1, 2024).

[67] Leaders of “Genesis II Church of Health and Healing,” who sold toxic bleach as fake “Miracle” cure for COVID-19 and other serious diseases, sentenced to more than 12 years in federal prison. United States Department of Justice. 2023. https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdfl/pr/leaders-genesis-ii-church-health-and-healing-who-sold-toxic-bleach-fake-miracle-cure (accessed Nov 1, 2024).

[68] Is hydroxychloroquine a treatment for COVID-19? Mayo Clinic. 2023. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/hydroxychloroquine-treatment-covid-19/art-20555331 (accessed Nov 1, 2024).

[69] Stokkermans TJ, Falkowitz DM, Trichonas G. Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine Toxicity. StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537086/ (accessed Nov 1, 2024).

[70] Li G, Zhang X, Zhang G. How the 5G Enabled the COVID-19 Pandemic Prevention and Control: Materiality, Affordance, and (De-)Spatialization. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(15): 8965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158965.