Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 4, 453-460, 2025

doi: 10.53854/liim-3304-11

CASE REPORTS

Otitis media caused by Vibrio cholerae in a child: a case report and literature review

Laura Venuti1, Giulia La Malfa1, Giulia Linares1,2, Valeria Garbo1,2, Giovanni Boncori1,2, Sara Ashtari1, Alessandra Cuccia1, Chiara Albano1,2, Giorgia Caruso3, Alba Polizzi3, Claudia Colomba1,2

1 Department of Health Promotion, Mother and Child Care, Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy;

2 Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, “G. Di Cristina” Hospital, ARNAS Civico Di Cristina Benfratelli, Palermo, Italy;

3 Laboratory of Microbiology and Virology, ARNAS Civico Di Cristina Benfratelli, Palermo, Italy.

Article received 9 September 2025 and accepted 10 November 2025

Corresponding author

Laura Venuti

E-mail: laura.venuti05@gmail.com

SUMMARY

A previously healthy 12-year-old boy was brought to our attention due to worsening respiratory symptoms and persistent emesis. During hospitalization, the child developed right-sided otalgia followed by otorrhea. An otorhinolaryngologic exam revealed tympanic membrane perforation and discharge. An ear sample culture yielded Vibrio cholerae. A computed tomography scan confirmed the presence of otitis media complicated with otomastoiditis. Treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate was complemented with ciprofloxacin and dexamethasone otic drops and led to a complete recovery without sequelae. While the child had no predisposing conditions, most published cases of otitis caused by Vibrio spp. describe a history of ear diseases or trauma and water exposure.

In a context where vibriosis is increasingly common, our case exemplifies the importance of considering Vibrio spp. among the possible causative agents of otitis, especially in coastal areas or when exposure to potentially contaminated water cannot be ruled out, even in the absence of predisposing conditions.

Keywords: Vibrio cholerae, vibriosis, otitis media, otomastoiditis, children

BACKGROUND

Bacteria of the Vibrio genus comprise more than 100 species, 12 of which are pathogenic to humans and can cause cholera and non-cholera infections [1].

Vibrio cholerae (V. cholerae) is responsible for cholera epidemics via the O1 and O139 serogroups, while non-O1/non-O139 V. cholerae (NOVC) and other halophilic Vibrio spp. (V. alginolyticus, V. fluvialis and V. parahaemolyticus) can cause a range of infections, including otological infections, collectively known as vibriosis [1].

We describe a case of acute otitis media (AOM) caused by V. cholerae in a child from Sicily and review the literature to characterize the clinical-epidemiological profile of this rare condition.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 12-year-old boy was brought to the Emergency Department (ED) in November 2024 for worsening respiratory symptoms, which had started about ten days earlier with a productive cough in the absence of fever. Two days before admission, the patient developed high-grade fever (up to 39.5 °C) and treatment with oral amoxicillin/clavulanate (1 g twice daily) and betamethasone (1 mg twice daily) was initiated. However, the child presented to the ED again with persistent fever and refractory vomiting (about 15 episodes) and was referred to the Infectious Diseases unit.

A thorough anamnesis did not reveal any allergies or other active pathologies. Contact with infected individuals was ruled out, while recent exposure to seawater could not be excluded. A Brugada pattern was identified about seven years earlier, and previous hospital admissions occurred due to gastroenteritis, acute kidney disease and asthma.

On initial physical examination, the boy appeared alert and in good general condition, showing mild dehydration but no signs of acute abdomen. On the first day of hospitalization, he developed a right-sided otalgia, prompting an otolaryngologic examination, which revealed a hyperaemic external auditory canal with an erythematous tympanic membrane. A slight increase in inflammatory markers was noted: leukocytes 11,780 cells/mm³ with 75.9% neutrophils; C-reactive protein (CRP) 4.39 mg/dL. A multiplex polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) panel for respiratory viruses on nasopharyngeal swab was negative.

On the second day, purulent otorrhea occurred, and a second otolaryngologic examination evidenced a tympanic membrane perforation. A sample of drained material, collected by the otorhinolaryngologist, led to the isolation a V. cholerae strain susceptible to ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin and meropenem, according to broth microdilution. No antibiotic susceptibility results were obtained by Vitek 2, as V. cholerae is not included in the antimicrobial susceptibility panel of this system.

The ear swab was cultivated on chocolate agar, Columbia blood agar, McConckey agar and Sabouraud dextrose agar plates (BD, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), which were incubated at 37 °C in aerobic conditions. Following 48 hours of incubation, β-haemolytic suspected colonies were isolated and underwent rapid identification through Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization - Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF, MALDI Biotyper, Bruker). No growth was observed on McConkey agar plate. To confirm the species, biochemical identification was carried out using an automated microbial identification system (Vitek 2 Compact, BioMèrieux, France). In vitro susceptibility testing was performed by broth microdilution (MicroScan, Beckman Coulter) and Vitek 2. The antibiotics tested were piperacillin-tazobactam, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, meropenem, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Susceptibility tests were interpreted according to European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) breakpoints for Vibrio spp., 2024 version. Clinical breakpoints for piperacillin-tazobactam, cefotaxime, levofloxacin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were outside the range of concentrations tested, therefore it was not possible to give an interpretation.

To rule out infection in other organs and systems, stool samples were tested through multiplex gastrointestinal PCR panels and stool cultures were performed, returning negative results for viruses and bacteria, including V. cholerae.

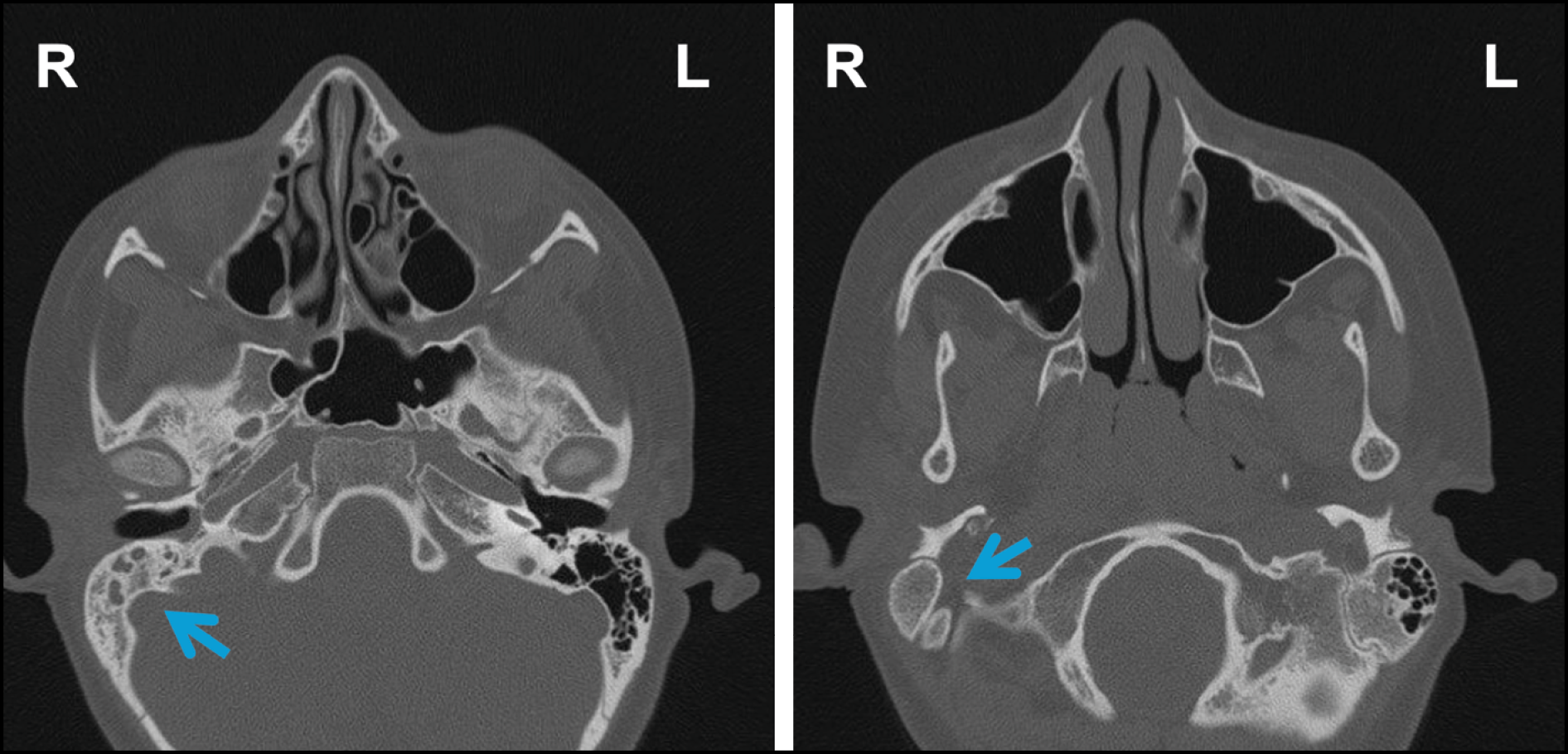

A high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1) of the temporal bones, combined with clinical and microbiological findings, led to the diagnosis of suppurative AOM complicated by otomastoiditis.

Figure 1 - Axial high-resolution CT scans of the temporal bones and paranasal sinuses, without contrast, showing inflammatory obliteration of the right middle ear and mastoid cells, without bone erosion or ossicular damage. The contralateral ear and paranasal sinuses are unremarkable. Pneumatization of the paranasal sinuses is within normal limits.

Treatment with oral amoxicillin-clavulanate was continued for a total of 21 days and complemented with ciprofloxacin and dexamethasone otic drops after aetiological diagnosis and antibiogram evaluation. The child’s fever and otorrhea resolved and no further episodes of otalgia were reported. Laboratory parameters normalized before discharge (leukocytes 7,070 cells/mm³; CRP 0.74 mg/dL). At outpatient follow-up, after ten days, there were no signs of recurrence or sequelae.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed and Scopus for cases of otitis caused by Vibrio spp. from inception until February 2025 using key words like “ear infection”, “otitis”, “Vibrio”. No filters or automation tools were applied. Inclusion criteria were (1) microbiological evidence of Vibrio spp., (2) documented otitis (external, internal or media), (3) inclusion of clinical-epidemiological data regarding cases of otitis, and (4) availability of the full-text article in English. Data collected from each report included patient demographics (age, sex), clinical features (type of otitis, symptoms), causative pathogen, treatments performed, antibiotic susceptibility, and outcomes.

RESULTS

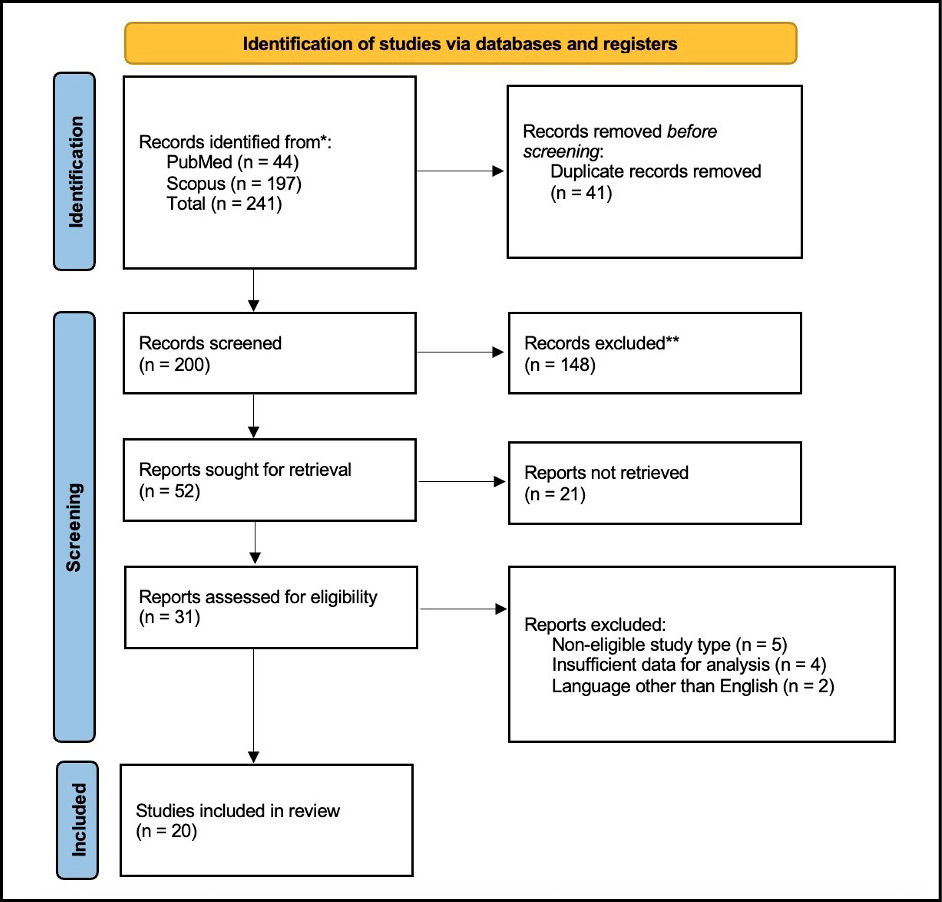

We identified 20 reports (Figure 2) describing a total of 35 cases of otitis caused by Vibrio spp. from 12 countries since 1973.

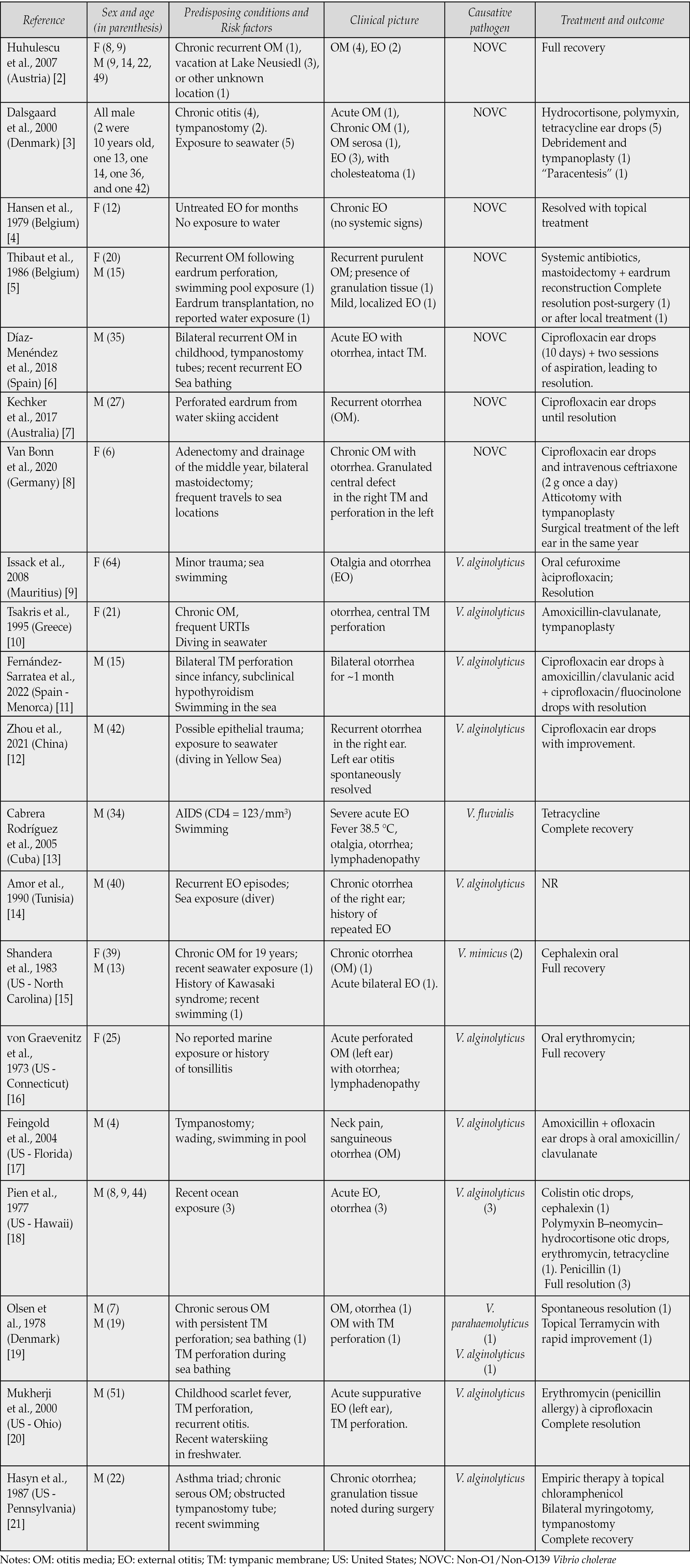

The main clinical-epidemiological aspects reported for each case are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2 - PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process for inclusion in this review.

Twenty-one cases were reported from European countries, nine cases from the United States, and five from other countries (Table 1).

Seventy-four percent of patients were male (n=26), while 26% were females (n=9). Age ranged from 4 to 64 years, with a mean of 23 years old and a median of 19 (IQR: 10-35). There was a slightly higher prevalence in adults (51%, n=18) over children (49%, n=17).

Table 1 – Clinical-epidemiological characteristics of published cases of otitis caused by Vibrio spp. For case series, the number of patients where a certain characteristic was present is indicated in parenthesis.

Most patients (85%) had predisposing conditions, including chronic or recurrent otitis, prior ear surgeries, application of tympanostomy tubes, and accidental trauma. Systemic comorbidities were also reported, such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), sequelae of scarlet fever, a history of asthmatic triad, and hypothyroidism. In most cases with available data (90%, n=28), exposure to a water source was identified.

External otitis was reported in 46% of cases (n=16), and otitis media in 54% (n=19). The infection was acute in 63% of cases (n=22).

Imaging diagnostic techniques were reported in three cases: in one case, an X-ray showed sclerosis of the mastoid bone; in two cases, CT scans helped rule out mastoiditis while evidencing soft tissue thickening of the auditory canal.

Culture was performed in 71% of cases (n=25). PCR was performed in 20% of cases (n=7), while MALDI-TOF MS was used in 11% of cases (n=4). In 51% of cases (n=18), otitis was caused by NOVC, in 37% of cases (n=13), the etiological agent was V. alginolyticus, and in the remaining four cases, other Vibrio spp. were identified (Table 1). Pathogens other than Vibrio spp. were identified in a minority of cases (n=10).

Treatment was in most cases medical, with surgery being required in a minority of cases (17%, n=6). Resistance was revealed in 70% of the cases where antibiotic susceptibility was reported (n=21).

Most patients had a full recovery (91%, n=32). In two cases, information on outcome was not reported. In one case, a second surgical intervention was necessary within the same year.

DISCUSSION

Over the past few decades, an increased incidence and a geographical expansion of non-cholera vibrio infections have been observed [1, 22]. Vibriosis outbreaks have been associated with heatwaves and hydrometeorological disasters, which can affect sea salinity levels, creating a more suitable environment for Vibrio spp. proliferation [1, 22, 23]. Unsurprisingly, exposure to water was reported in most of the cases we reviewed (whether to salty, brackish or freshwater), and infection often occurred during summer, reflecting the seasonal pattern of vibriosis [1, 23]. In our case, despite the infection not occurring in the summer months, sea bathing could not be excluded given the Sicilian climate.

Typically, AOM follows a viral upper respiratory tract infection and is caused by pathogens such as Staphylococcal spp., Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, reaching the middle ear from the nasopharynx. Vibrio spp. are uncommonly associated with both external otitis and otitis media. Among the reports we collected, NOVC were the most common vibrios (51%), followed by V. alginolyticus (37%).

In most of these cases (85%), predisposing factors were documented (Table 1); in contrast, in our patient, no predisposing condition or history of ear disease was identified, and contamination was deemed unlikely given the negative faecal culture.

While a secondary bacterial infection due to transient tubal dysfunction cannot be excluded, the sequence of findings (initial erythema of the tympanic membrane followed by otorrhea and perforation) suggests that V. cholerae might have caused a primary external ear infection that later progressed to the middle ear. Therefore, this case represents an uncommon example of complicated AOM with an atypical aetiology in the absence of the usual risk factors.

Regarding treatment of AOM in children, most recommend a watchful waiting approach (82%), and the main indications for antibiotic treatment are tympanic membrane perforation or otorrhoea (93%) [24]. Antibiotics were used in most published cases of Vibrio spp.-related otitis, and surgery was required in six (17%). Resistance was reported in 70% of the cases with available information (n=21). In our case, treatment with oral amoxicillin-clavulanate, initiated prior to hospital admission, was integrated with otic drops of ciprofloxacin and dexamethasone after aetiological diagnosis and antibiogram evaluation to reduce the resistance risk and improve drug delivery.

In conclusion, with increasing vibriosis cases, clinicians should consider Vibrio spp. among the potential causes of otitis, particularly in patients with a history of exposure to potentially contaminated water, even in the absence of predisposing factors. Complications of AOM can be severe; thus, given the importance of clinical suspicion in guiding proper sample collection and pathogen isolation, awareness of this uncommon aetiology among parents and healthcare providers is crucial. Increased vigilance can help promote preventive measures, such as avoiding swimming or bathing in the presence of tympanic membrane lesions, and support timely diagnosis, minimizing the likelihood of complications and antibiotic resistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interests.

Funding

No funding was required for this research.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Rachel Horsfield (MD) for reviewing the manuscript for clearance and language accuracy.

Ethics and consent to publish declaration

This report of a single anonymized clinical case with a review of previously published cases does not include any identifiable personal data. As such, formal ethical approval was not applicable, and informed consent was not required. All data presented are from standard clinical practice and the scientific literature.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization (LV, GLM, CC); methodology (LV, GC, AP, CC); investigation (LV, GLM, GL, VG, GB, SA, AC, GC, AP); resources (LV, GLM, GL, VG, GB, SA, AC, GC, AP, CC); supervision (VG, CC); project administration (CC); validation (CC); visualization (LV, GLM); formal analysis (LV, GLM, GL, VG, GB, SA, AC); writing - first draft (LV, GLM, GC, AP, GL); writing - revision and editing (LV, VG, CC); patient care / clinical management (GLM, GL, VG, GB, SA, AC, GC, AP, CC).

REFERENCES

[1] Baker-Austin C, Oliver JD, Alam M, et al. Vibrio spp. infections. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018; 4: 1-19.

[2] Huhulescu S, Indra A, Feierl G, et al. Occurrence of Vibrio cholerae serogroups other than O1 and O139 in Austria. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007; 119: 235-241.

[3] Dalsgaard A, Forslund A, Hesselbjerg A, et al. Clinical manifestations and characterization of extra-intestinal Vibrio cholerae non-O1, non-O139 infections in Denmark. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2000; 6: 625-627.

[4] Hansen W, Crokaert F, Yourassowsky E. Two strains of Vibrio species with unusual biochemical features isolated from ear tracts. J Clin Microbiol 1979; 9: 152-153.

[5] Thibaut K, Van De Heyning P, Pattyn SR. Isolation of non-01 V. cholerae from ear tracts. Eur J Epidemiol.1986; 2: 316-317.

[6] Díaz-Menéndez M, Alguacil-Guillén M, Bloise I, et al. A case of otitis externa caused by non-01/non-0139 Vibrio cholerae after exposure at a Mediterranean bathing site. Rev Esp QuimioteR. 2018; 31: 295-297.

[7] Kechker P, Senderovich Y, Ken-Dror S, et al. Otitis Media Caused by V. cholerae O100: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Front Microbiol. 2017; 8: 1619.

[8] Van Bonn SM, Schraven SP, Schuldt T, et al. Chronic otitis media following infection by non-O1/non-O139 Vibrio cholerae: A case report and review of the literature. EuJMI. 2020; 10: 186-191.

[9] Issack MI, Appiah D, Rassoul A, et al. Extraintestinal Vibrio infections in Mauritius. J Infect Dev Ctries 2008; 2: 397-399.

[10] Tsakris A, Psifidis A, Douboyas J. Complicated suppurative otitis media in a Greek diver due to a marine halophilic vibrio sp. J Laryngol Otol. 1995; 109: 1082-1084.

[11] Paula Fernández-Sarratea M, Beteta-López A, Ezcurra-Hernández P, et al. Chronic simple otitis media due to Vibrio alginolyticus. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022; 40: 582-583.

[12] Zhou K, Tian K, Liu X, et al. Characteristic and Otopathogenic Analysis of a Vibrio alginolyticus Strain Responsible for Chronic Otitis Externa in China. Front Microbiol. 2021; 12: 750642.

[13] Cabrera Rodríguez LE, Monroy SP, Morier L, et al. Severe otitis due to Vibrio fluvialis in a patient with AIDs: first report in the world. Rev Cubana Med Trop. 2005; 57: 154-155.

[14] Amor A, Barguellil F. Infection auriculaire a Vibrio alginolyticus. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 1990; 20: 618-619.

[15] Shandera WX, Johnston JM, Davis BR, et al. Disease from infection with Vibrio mimicus, a newly recognized Vibrio species. Clinical characteristics and edipemiology. Ann Intern Med. 1983; 99: 169-171.

[16] Von Graevenitz A, Currington GO. Halophilic vibrios from extraintestinal lesions in man. Infection. 1973; 1: 54-58.

[17] Feingold MH, Kumar ML. Otitis media associated with Vibrio alginolyticus in a child with pressure-equalizing tubes. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004; 23: 475-476.

[18] Pien F, Lee K, Higa H. Vibrio alginolyticus infections in Hawaii. J Clin Microbiol. 1977; 5: 670-672.

[19] Olsen H. Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from discharge from the ear in two patients exposed to sea water. Acta Pathologica Microbiologica Scandinavica Section B Microbiology. 1978; 86B: 247-248.

[20] Mukherji A, Schroeder S, Deyling C, et al. An Unusual Source of Vibrio alginolyticus-Associated Otitis: Prolonged Colonization or Freshwater Exposure? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000; 126: 790.

[21] Hasyn JJ, Mauer TP, Warner R, et al. Isolation of Vibrio alginolyticus from a patient with chronic otitis media: Report of case and review of biochemical activity. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1987; 87: 94-96.

[22] Trinanes J, Martinez-Urtaza J. Future scenarios of risk of Vibrio infections in a warming planet: a global mapping study. Lancet Planet Health. 2021; 5: e426-e435.

[23] Amato E, Riess M, Thomas-Lopez D, et al. Epidemiological and microbiological investigation of a large increase in vibriosis, northern Europe, 2018. Euro Surveill. 2022; 27: 2101088.

[24] Hg S, Je D, Rg N, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for acute otitis media in children: a systematic review and appraisal of European national guidelines. BMJ open; 10. Epub ahead of print 5 May 2020. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035343.