Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 4, 448-452, 2025

doi: 10.53854/liim-3304-10

CASE REPORTS

Expanding the causes of Fever of Unknown Origin in immunocompromised patients: report of two cases highlighting the role of SARS-CoV-2

Carmelina Calitri, Francesca Romano, Andrea Perinzano, Barbara Rizzello, Marco Domenico Carbutto, Fabio Antonino Ranzani, Roberto Angilletta, Marco Mussa, Andrea Calcagno

Department of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, Amedeo di Savoia Hospital, University of Turin, Turin, Italy.

Article received 28 July 2025 and accepted 19 October 2025

Corresponding author

Carmelina Calitri

E-mail: carmelina_calitri@libero.it

SUMMARY

Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO) remains a diagnostic challenge for clinicians, with multiple infectious and non-infectious etiologies. SARS-CoV-2 can determine a prolonged viral shedding in the immunocompromised host, firstly in those receiving B-cell targeted therapies, being responsible of persistent infection which may configure as a FUO. We report two cases of long-lasting fever in patients with multiple sclerosis and B-cell depletion, finally diagnosed as COVID-19. We suggest the inclusion of SARS-CoV-2 testing in the differential diagnosis of FUO.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, FUO, immunocompromised host, B-cell depletion.

INTRODUCTION

More than 60 years after the first definition by Petersdorf and Beeson, Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO) still remains a diagnostic challenge. The absence of an identified cause of fever, despite reasonable investigations in the in/outpatient context, and the persistence of fever for a sufficient time to rule out self-limiting conditions are the core features of FUO [1, 2].

Multiple and disparate infectious disease processes are involved into FUO diagnostic workup. Historically, it has been divided into classic, nosocomial, immunodeficiency-related, and travel-associated types: such a classification provides a useful framework to approach patients [2]. Immunocompromised subjects are at risk for a broad range of opportunistic infections in addition to common conditions. Capsulate and intracellular bacteria, herpes viruses (in particular CMV and EBV), mycobacteria, fungal infections may cause FUO in patients with immunological deficits, each one related to a predisposing immune system deficit [2, 3].

Persistent infections by ‘short-course’ viruses in people who are immunocompromised have been observed for many respiratory viruses, as cancer, rheumatologic diseases, autoimmune processes, and their associated therapies can compromise innate and adaptive immune response, making patients weakened and unable to control the virus, and facilitating infection even after low inoculum exposures [4, 5].

Here we describe two multiple sclerosis (MS) cases under CD20-targeted therapies affected by FUO related to persistent COVID-19 disease.

Case 1

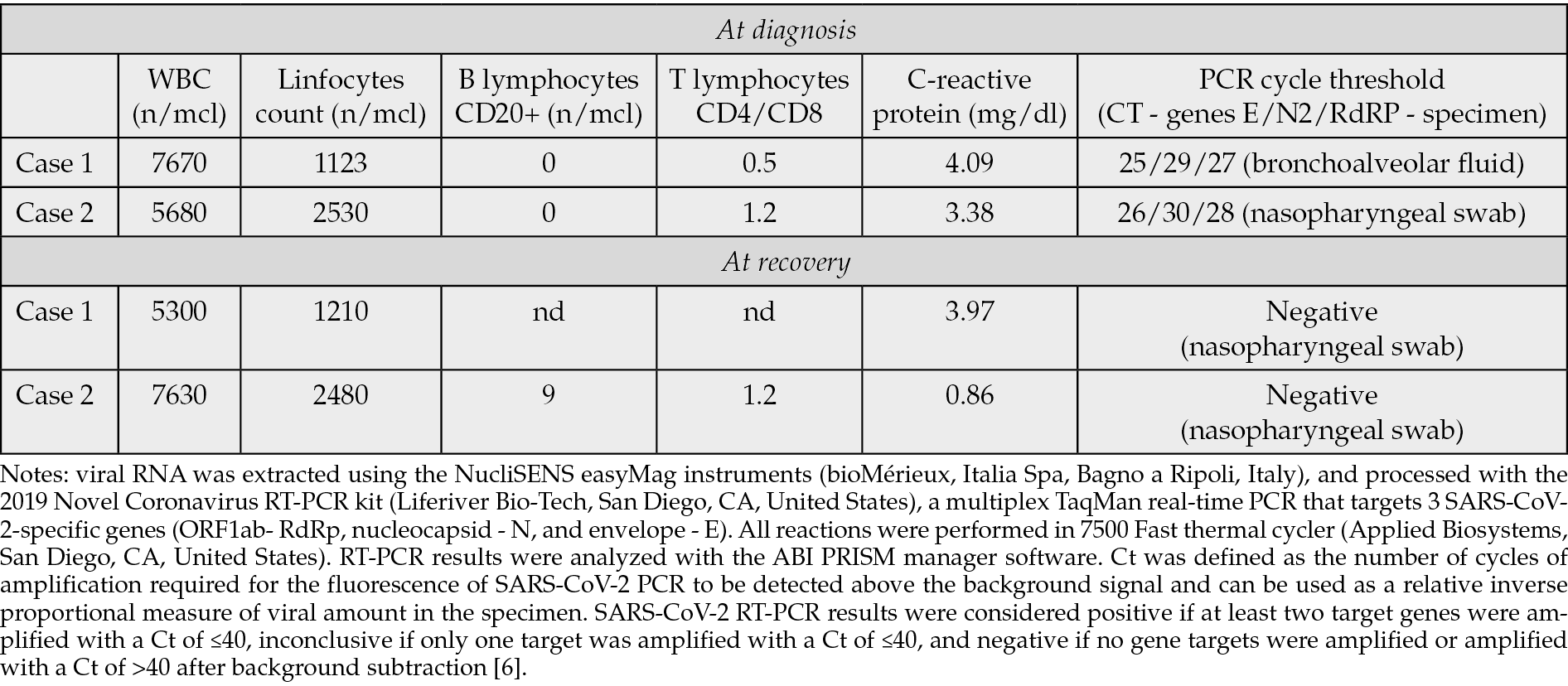

On April 2024, a 56-year-old male patient was referred to our Center for a 2-month fever with headache and mild cough. Fever (up to 39°C) started after his periodical anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody treatment (rituximab) for MS. He underwent multiple antibiotic therapies, initially for a suspected urinary tract infection, then for pneumonia (with bilateral, peripheral consolidations found at the Computed Tomography - CT scan). A Positron Emission Tomography-CT (PET-TC) confirmed an intense and diffuse uptake of FDG within the lungs. He was vaccinated for SARS-CoV-2 with at least 4 doses together with seasonal influenza. Blood cultures, Quantiferon TB, beta-D glucan, herpes polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests on blood, HIV and hepatitis serologies were negative. A multiplex PCR test for respiratory viruses on nasal swab resulted negative. A specific SARS-CoV-2 Real-Time (RT)-PCR on nasopharyngeal swab (Liferiver Bio-Tech, San Diego, CA, United States) was repeated two times and was always negative. The patient underwent bronchoscopy: cultures, M. tuberculosis stain and PCR, galactomannans, P. jirovecii PCR and viral PCR on bronchoalveolar (BAL) lavage fluid were negative. No neoplastic cells were found. On a second evaluation on the same BAL sample, RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 resulted positive (Table 1). A ten-day off-label course of intravenous remdesivir with oral nirmatrelvir/ritonavir was prescribed in the same day. No more febrile episodes were found after the first 3 days of therapy and the cough totally disappeared in 1 week. SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR on nasal swab always maintained negative. The patient underwent a chest CT after one month from the end of the therapy, with evidence of pneumonia resolution. At follow up visits no relapse of fever or other respiratory symptoms were noted. On June 2024 he could re-start his periodical rituximab therapy.

Table 1 - Patients blood work at diagnosis and recovery.

Case 2

A 52-year-old female patient has a relapsing-remitting MS on semiannual anti-CD20 therapy (ocrelizumab). She received at least 4 mRNA-vaccine doses for SARS-CoV-2. She developed continuous fever (up to 39°C), general malaise, and productive cough. Various empiric antibiotic therapies were prescribed with no improvements. At the CT scan a multifocal parenchymal thickenings with fuzzy ground-glass margins in the upper left lobe, middle lobe, and basal pyramids were found. Pulmonary function testing evidenced abnormal gas exchances. Microbiological and virological tests (cultures, viral PCR, M. tuberculosis stain and PCR, P. jirovecii PCR, galattomannan) performed on bronchoalveolar lavage were negative. CD4/CD8 ratio on BAL was 0.4. A diagnostic hypothesis of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) was formulated by pneumologists, and an oral prednisone therapy was started. Three weeks after (April 2024) she was admitted to our Department for persistence of symptoms. She was in the tapering phase of the steroid therapy (prednisone, 12.5 mg/day). During hospitalization, a worsening of the known ground-glass thickening with modest consolidative component in the upper right lobe was documented at CT scan. For the first time, a RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 was performed on a nasopharyngeal swab and tested positive (Liferiver Bio-Tech, San Diego, CA, United States, table 1). On the same day, the patient started the off-label association of intravenous remdesivir and oral nirmatrelvir/ritonavir carried on for 10 days. Prednisone therapy was promptly reduced at a dosage of 5 mg/day, and stopped in few days. She became afebrile in the 2th day of treatment, cough progressively disappeared. SARS-CoV-2 PCR on nasal swab resulted negative the last day of the 10-course treatment. The patient underwent a chest CT after one month from dismission and significant improvement of lung parenchymal alterations was noted. At the 6-month pneumological follow up no relapse of respiratory symptoms appeared.

DISCUSSION

Persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection can be responsible of FUO in immunocompromised individuals.

It is very unusual to detect SARS-CoV-2 in the upper respiratory tract for longer than 1 month in immunocompetent people, so COVID-19 appears as a self-limited disease in healthy patients, who typically recover within 5-7 days [4]. Conversely, a potential hyperacute and progressive course can be observed in people with chronic diseases. The weakened immune system of immunocompromised people often fails to clear the virus, leading them to persistent infections with high viral titers and subsequent major risk of prolonged hospitalization, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission, and mortality. In line with recent papers we can define SARS-CoV-2 infection as persistent when replication has an unusual long duration (at least 30 days) after symptoms onset [4, 7].

Innate and adaptive immunity work synergistically to prevent, limit, and clear SARS-CoV-2 infection. CD8+ T cells are critical for mediating the antiviral response in acute infection, while the coordination between elements of the adaptive immunity as virus-specific B cells, CD4+ T cells and antibodies is responsible for the effective viral clearance and the prevention of future infections.

Therefore, different forms of immune deficit can differentially predispose to SARS-CoV-2 persistence. Individuals with suppressed innate immunity may experience a higher incidence of infection, but they are able to achieve viral clearance. Patients with impaired adaptive cellular immunity have a high risk of death from acute infection. Patients with impaired adaptive humoral immunity (i.e., B-cell malignancies and B-cell targeting therapy) have a high risk of prolonged viral shedding, viral rebound, and chronic infection [8, 9].

B cell dysfunction from anti-B cell therapy is the most commonly described cause of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection [4]. People with MS, as our patients, have a probability of severe outcomes 2 to 5 times higher than in age and sex-matched populations, both for the immune-mediated nature of the disease and the immunomodulatory therapies which potentially increase the risk of viral infection. Exposure to B-cell depleting agents (such as rituximab and ocrelizumab) is associated with a 2- to 4.5 elevated risk for severe COVID-19 in the MS population compared to people using other disease-modifying therapies [10, 11].

As a consequence of B-cell depletion, the neutralizing antibody response is reduced in such individuals. SARS-CoV-2 infection cannot be cleared, so patients can test positive for SARS-CoV-2 on reverse-transcriptase PCR for prolonged periods of time (weeks to months) with a low cycle threshold (which suggests an intense viral replication). As found in our patients, they can develop recurrent respiratory symptoms, migratory pulmonary infiltrates, and require hospitalization. Viral genome sequencing demonstrated persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection with the same strain, rather than co-infection or reinfection, in these individuals [4]. The same mechanism has been described for the persistence of other respiratory viruses, such as influenza, parainfluenza and rhinovirus, together with multiple non-respiratory viruses that usually cause short-term infections, including dengue virus, Zika virus and norovirus [4].

SARS-CoV-2 vaccination prevents severe disease in the general population, but the COVID-19 risk remained elevated across immunocompromised groups in terms of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality [8]. Anti-CD20 treatments affect the patient’s response both to infection and to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, as B-cell depletion results in decreased induced spike specific antibody production. However, incomplete responses may still provide some protection, as T cell-mediated immune response is also elicited by vaccination [10, 11]. Moreover, the cross reactivity between SARS-CoV-2 and other coronavirus may influence patient protection. CD20 expression is lacking on plasma cells, so patients under rituximab therapy can maintain specific antibodies production [5]. For the same reason, individuals treated with B cell depleting therapies retain humoral immunity to childhood vaccines and can already mount robust memory responses following vaccination against influenza despite substantial humoral and cellular immunodeficiency [5].

The IDSA panel suggests using standard nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs, RT-PCR or laboratory-based NAAT) over rapid Antigen (Ag) tests in symptomatic patients with possible COVID-19, due to their higher sensitivity and thus the reduced risk of missing a diagnosis. Antigen tests sensitivity has been optimized within the first 5 days of symptoms. However, a negative test result should be confirmed with a standard NAAT when the COVID-19 clinical suspicion remains and no alternative diagnosis has been reached [12]. The PCR cycle threshold can be used to estimate viral loads: it quantifies the viral burden in samples like nasopharyngeal swab, giving a crude assessment for presence of viable virus. In immunocompetent hosts, a persistent PCR is not associated with a transmissible virus, while in immunocompromised patients prolonged PCR positivity may reflect culturable viruses, suggesting that immune defects might significantly contribute to SARS-CoV-2 viral persistence [5].

There is no therapeutic consensus on COVID-19 treatment in immunocompromised patients with persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection [13-15]. Cohort studies suggest the efficacy of antivirals combination in treating RNA viruses, particularly when targeting different mechanisms of viral replication, as in the case for the off-label association of remdesivir (polymerase) plus nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (protease). D’Abramo et al included 50 people with B-cell depletion among a cohort of 88 immunocompromised COVID-19 patients: those treated with combination therapies (and among them, the majority with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir plus iv remdesivir) experienced a significant reduction in both length of hospitalization and time to negative SARS-CoV-2 molecular nasopharyngeal swab compared to those in antiviral monotherapy [8]. Similar results were reported by other Authors, finding the high efficacy of combination treatment in terms of early virological response and 30-day virological and clinical response [16, 17].

In conclusion, SARS-CoV-2 can be responsible of persistent infection in the immunocompromised host, firstly in those receiving B-cell targeted therapies as antiCD20 ones. B cell depleted individuals manifested a prolonged viral shedding with mild symptomatic but “chronic” disease which may configure as a FUO. SARS-CoV-2 detection should be included among the diagnostic work up of FUO particularly in immunocompromised patients.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This is an own work of the Authors. No funding was used for its compiling.

REFERENCES

[1] Mulders-Manders C, Simon A, Bleeker-Rovers C. Fever of unknown origin. Clin Med (Lond). 2015; 15(3): 280-284.

[2] Haidar G, Singh N. Fever of Unknown Origin. N Engl J Med. 2022; 386(5): 463-477.

[3] Azoulay E, Russell L, Van de Louw A, et al. Diagnosis of severe respiratory infections in immunocompromised patients. Intensive Care Med. 2020; 46(2): 298-314.

[4] Sigal A, Neher RA, Lessells RJ. The consequences of SARS-CoV-2 within-host persistence. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2025; 23(5): 288-302.

[5] DeWolf S, Laracy JC, Perales MA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 in immunocompromised individuals. Immunity. 2022; 55(10): 1779-1798.

[6] Trunfio M, Richiardi L, Alladio F, et al. Determinants of SARS-CoV-2 Contagiousness in Household Contacts of Symptomatic Adult Index Cases. Front Microbiol. 2022; 13: 829393.

[7] Machkovech HM, Hahn AM, Garonzik Wang J, et al. Persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection: significance and implications. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024; 24(7): e453-e462.

[8] D’Abramo A, Vita S, Beccacece A, et al. B-cell-depleted patients with persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection: combination therapy or monotherapy? A real-world experience. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024; 11: 1344267.

[9] Aydillo T, Gonzalez-Reiche AS, Aslam S, et al. Shedding of Viable SARS-CoV-2 after Immunosuppressive Therapy for Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(26): 2586-2588.

[10] Pugliatti M, Berger T, Hartung HP, et al. Multiple sclerosis in the era of COVID-19: disease course, DMTs and SARS-CoV2 vaccinations. Curr Opin Neurol. 2022; 35(3): 319-327.

[11] Prosperini L, Arrambide G, Celius EG, et al. COVID-19 and multiple sclerosis: challenges and lessons for patient care. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024; 44: 100979.

[12] Hayden MK, Hanson KE, Englund JA, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Diagnosis of COVID-19: Molecular Diagnostic Testing. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2023; Version 3.0.0. Available at https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-diagnostics/. (Accessed on March 13, 2025).

[13] Venturini S, Orso D, Cugini F et al. Mortality predictors in hospitalised COVID-19 patients and the role of anti- SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies and remdesivir. Infez Med. 2023; 31(2): 215-224.

[14] Cogliati Dezza F, Oliva A, Mauro V, et al. Real-life use of remdesivir-containing regimens in COVID-19: a retrospective case-control study. Infez Med. 2022; 30(2): 211-222.

[15] Velati D, Puoti M. Real-world experience with therapies for SARS-CoV-2: Lessons from the Italian COVID-19 studies. Infez Med. 2025; 33(1): 64-75.

[16] Mikulska M, Sepulcri C, Dentone C, et al. Triple Combination Therapy With 2 Antivirals and Monoclonal Antibodies for Persistent or Relapsed Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection in Immunocompromised Patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2023; 77(2): 280-286.

[17] Longo BM, Venuti F, Gaviraghi A, et al. Sequential or Combination Treatments as Rescue Therapies in Immunocompromised Patients with Persistent SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Omicron Era: A Case Series. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023; 12(9): 1460.