Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 4, 355-369, 2025

REVIEWS

The Role of Big Data in Developing Innovative Predictive Learning Models for Neglected Tropical Diseases within the New Generation of the Evidence-Based Medicine Pyramid

Jhon Víctor Vidal-Durango1,2, Johana Galván-Barrios3, Juan David Reyes-Duque4, Ivan David Lozada-Martinez3,5

1 Facultad de Ciencias Básicas, Universidad de Córdoba, Montería, Colombia;

2 Programa de Doctorado en Innovación, Universidad de la Costa, Barranquilla, Colombia;

3 Biomedical Scientometrics and Evidence-Based Research Unit, Department of Health Sciences, Universidad de la Costa, Barranquilla, Colombia;

4 Facultad de Ciencias para la Salud, Universidad de Manizales, Caldas, Manizales, Colombia;

5 Clínica Iberoamérica, Barranquilla, Colombia.

Article received 25 August 2025 and accepted 13 October 2025

Corresponding author

Ivan David Lozada-Martinez

E-mail: ilozada@cuc.edu.co

SUMMARY

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) have been identified as a major global health burden, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, yet limited scientific attention has been given to them. Simultaneously, the emergence of Big Data and artificial intelligence has been transforming the way medical evidence is produced. Despite this, minimal integration between Big Data approaches and NTDs research has been observed. To explore this gap, a narrative review with a brief scientometrics analysis was conducted alongside a critical review of 13 original studies and systematic reviews that applied Big Data to NTDs. Studies were assessed according to design, objectives, disease focus, and geographic scope. Findings revealed a significant disparity: although extensive literature exists on Big Data and on NTDs separately, only a small number of studies combine both. Most of these were focused on dengue, with limited geographic representation and methodological consistency. These results suggest that the field remains underdeveloped and fragmented. Opportunities for interdisciplinary and data-intensive approaches have not been fully utilized. It is proposed that, by aligning Big Data applications with the new generation of the evidence-based medicine pyramid, more inclusive, predictive, and context-sensitive research on NTDs could be enabled, supporting equitable health decision-making in historically neglected populations.

Keywords: Neglected diseases, big data, predictive learning models, artificial intelligence, evidence-based medicine.

INTRODUCTION

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) continue to afflict more than a billion people worldwide, disproportionately impacting low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and contributing significantly to disability, poverty, and premature death [1]. Despite this burden, NTDs remain underrepresented in the global research agenda, receiving limited funding and scientific attention relative to their public health impact [2]. This persistent mismatch between disease burden and scientific investment, what has been described as an “epistemic injustice”, raises critical concerns about how health research priorities are defined, and for whom knowledge is being produced [3, 4]. In this context, epistemic injustice refers to the systematic exclusion of the voices and realities of those most affected by NTDs from the processes of knowledge production and decision-making. By privileging evidence generated in high-income settings, global health research often overlooks the perspectives and needs of endemic populations.

Despite notable advances under the World Health Organization (WHO) 2030 roadmap, progress remains uneven across diseases and regions, with persistent gaps in surveillance, diagnostics, and implementation capacity [1, 4]. This sustained mismatch between burden and research investment underscores why a broader, data-enabled evidence ecosystem is urgently needed to inform earlier detection, smarter targeting, and context-sensitive interventions in endemic settings [1, 3, 4].

Traditional paradigms of evidence-based medicine (EBM), long guided by a rigid hierarchy of evidence privileging randomized controlled trials (RCTs), have struggled to adapt to the complexities of real-world health problems in resource-limited settings [5, 6]. However, recent conceptual advances propose a transformation in how we define and value evidence [7]. A new generation of the EBM pyramid has emerged, one that integrates large-scale, multidimensional data sources, including big data, real-world evidence, and machine learning-derived insights, into the heart of medical reasoning and decision-making [7, 8].

Implementing the new generation of the EBM pyramid in LMICs requires a pragmatic and context-sensitive approach [7]. Infrastructural limitations, such as limited internet connectivity, restricted computational power, and fragmented data systems, make it unrealistic to replicate the same models used in high-resource settings [6]. Instead, progress can be achieved by building on what is already available: freely accessible data sources like remote sensing, weather archives, and routine epidemiological records; simple but transparent analytical pipelines that can run on modest infrastructure; and open-source tools that facilitate reproducibility [6-8]. Crucially, implementation must be guided by local ownership, with endemic-country researchers leading the design of models that reflect their own epidemiological realities [8]. This stepwise approach, starting with feasible, low-cost solutions and progressively scaling up, ensures that Big Data does not remain a distant aspiration, but becomes a usable and sustainable tool for health decision-making in resource-limited settings.

In parallel, scientific developments have shown that big data approaches, when applied to NTDs such as dengue, chikungunya, or schistosomiasis, can powerfully inform predictive models of transmission, anticipate outbreaks, and optimize targeted interventions [9-11]. Case studies across South America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia have leveraged satellite imagery, mobile phone records, environmental variables, and social media signals to model disease spread with increasing accuracy [9, 11, 12]. However, these applications remain fragmented, opportunistic, and rarely integrated into long-term health planning [9-12]. Moreover, the intersection of big data science and NTDs research remains dramatically underexplored: a preliminary scientometrics analysis reveals a striking paucity of publications connecting these two domains, signaling a significant knowledge gap and an urgent opportunity for scientific advancement [13].

Compounding this issue is a broader challenge: how to meaningfully validate and incorporate these novel data streams into the existing architecture of clinical and public health decision-making [14, 15]. If big data is to fulfill its promise, particularly in under-researched disease contexts, it must be aligned with the evolving philosophical and methodological foundations of medical evidence, a challenge that is both scientific and epistemological in nature [16]. This is particularly urgent in low-income countries (LICs) and LMICs, which bear nearly the entire burden of disease caused by NTDs [1].

This narrative review critically explores the role of big data in developing innovative predictive learning models for NTDs, contextualized within the new generation of the EBM pyramid. Drawing from recent empirical examples and a scientometrics snapshot of the field, we argue that embracing this paradigm shift is essential for closing the equity gap in global health research. By expanding what counts as valid evidence and who benefits from it, big data can play a transformative role in realigning scientific priorities with population needs, especially those long neglected by traditional biomedical research.

During the preparation of this manuscript, an artificial intelligence tool was used exclusively to assist with linguistic refinement and to improve grammatical and semantic clarity. All scientific content, data interpretation, and conclusions were entirely conceived and validated by the authors, who take full responsibility for the integrity and rigor of the work.

THE TRANSITION TOWARD A NEW GENERATION OF THE EBM PYRAMID: INTEGRATING BIG DATA INTO THE FOUNDATIONS OF HEALTH EVIDENCE

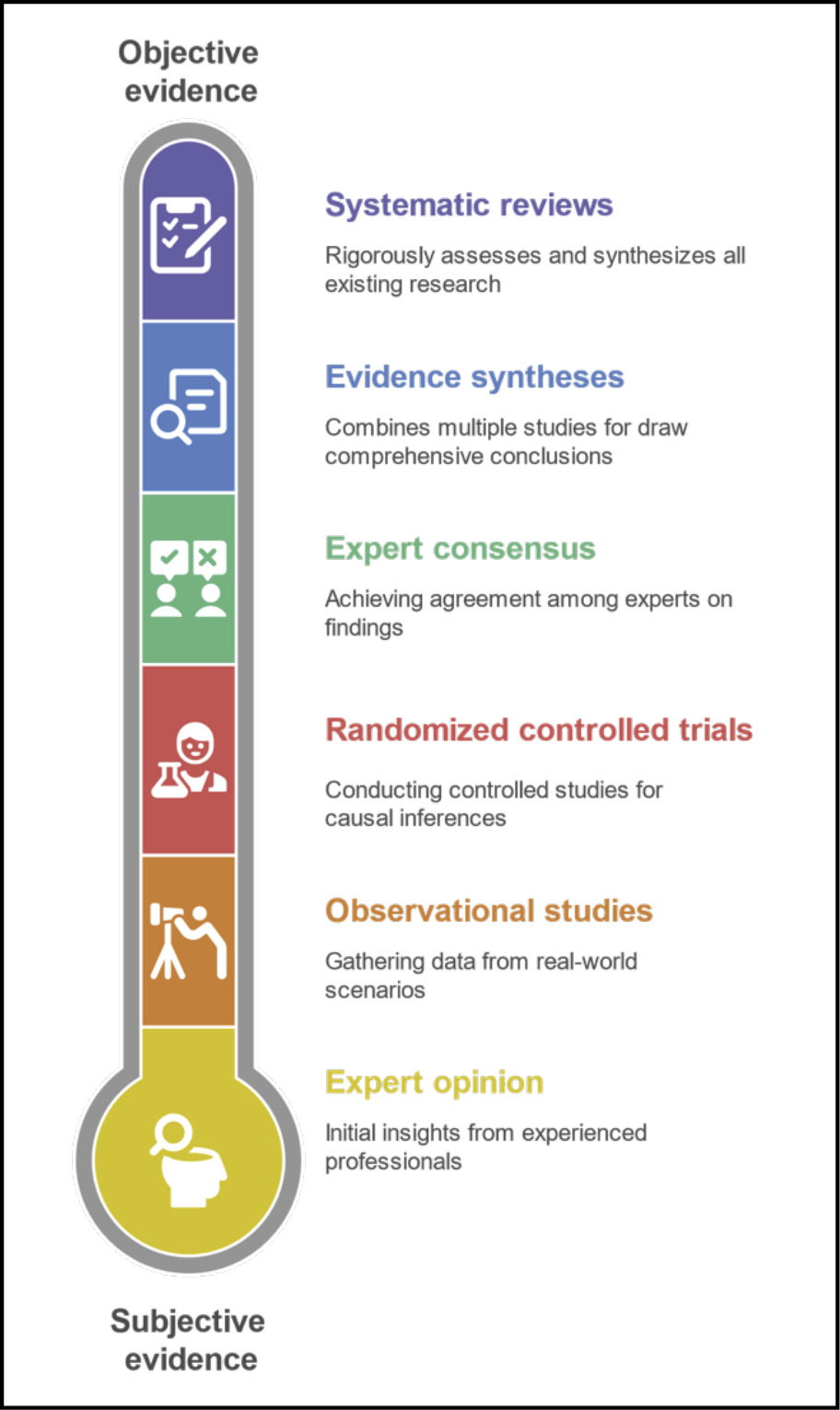

For over three decades, EBM has served as the gold standard for evaluating clinical practices and guiding health decisions [5]. Its conceptual foundation, the so-called “evidence pyramid”, prioritized RCTs and systematic reviews as the highest forms of evidence, while observational studies, expert opinion, and case reports were tradition-ally relegated to lower tiers (Figure 1) [17]. This figure illustrates the classical hierarchy of evidence as conceptualized in traditional EBM, structured from more subjective forms of evidence (base) to more objective and methodologically rigorous forms (top). Each level not only reflects increasing methodological robustness but also determines the typology of scientific publications that are typically associated with it. This linear and hierarchical model has historically guided clinical decision-making and health policy formation.

Figure 1 - Hierarchy of traditional evidence in evidence-based medicine (EBM).

While this hierarchy succeeded in promoting rigorous experimentation, it has also faced important limitations, particularly in its capacity to respond to complex, context-sensitive, and multifactorial health challenges, such as those presented by NTDs [18].

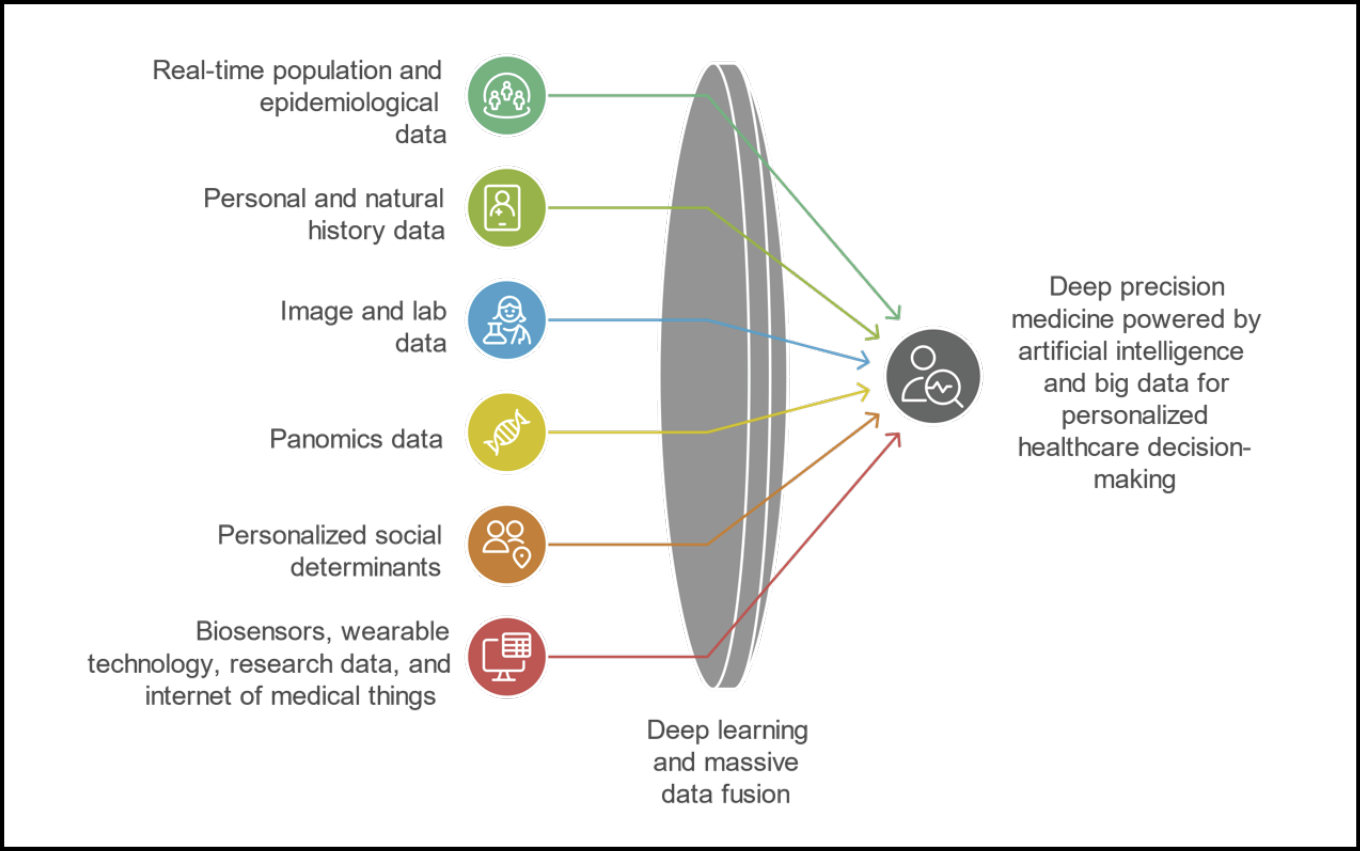

In recent years, the EBM pyramid has undergone a profound transformation [5]. A new generation of this model has emerged, one that recognizes the growing role of big data, machine learning, real-world evidence, and other computational approaches in generating clinically relevant knowledge (Figure 2) [7]. This figure illustrates the transition from a rigid hierarchical model of evidence (as shown in Figure 1) to a horizontal, multidimensional, and integrative ecosystem of evidence. In this new paradigm, scientific validity is no longer determined solely by study design, but also by the richness, diversity, and fusion of data sources. By leveraging advanced computational tools such as deep learning, artificial intelligence, and massive data fusion, evidence can now be generated from a variety of non-traditional and previously inaccessible sources, including: real-time epidemiological and population data (e.g., outbreak surveillance, case mapping); personal and natural history data (e.g., longitudinal clinical trajectories); imaging and laboratory data (e.g., radiology, biomarkers); panomics data (e.g., genomics, proteomics, metabolomics); personalized social determinants of health (e.g., socioeconomic status, education, environment); data from wearable devices and internet of medical things (e.g., continuous biometric monitoring, activity tracking).

Figure 2 - New evidence ecosystem: integrating heterogeneous data sources through deep learning for personalized decision-making.

In this model, no single data source holds intrinsic superiority. Instead, validity arises from the intelligent integration of diverse information streams, contextualized to the patient or population under study. This approach represents a fundamental shift in evidence generation: from hierarchical exclusion to dynamic inclusion, from controlled ideal conditions to real-world complexity, and from generalized knowledge to personalized insight. This shift does not aim to dismantle traditional EBM principles, but rather to expand them, to reflect the changing nature of scientific inquiry in an era defined by vast, heterogeneous, and high-velocity data flows [7].

At the core of this transition is the realization that many variables influencing health outcomes, such as environmental conditions, biological variables, population/epidemiological data, panomics, socioeconomic status, human mobility patterns, or even digital behaviors, have historically remained outside the reach of conventional study designs (Figure 2) [7]. These variables, while often critical to understanding disease risk and intervention impact, were either impossible to measure or too costly and time-consuming to incorporate using traditional methods [7]. As a result, many health studies operated under conditions of informational scarcity, relying on simplified models of reality that excluded essential social, ecological, or behavioral determinants [7].

If this trend continues, achieving the goal of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based deep precision medicine will not be possible [19]. This approach is essential for enabling personalized healthcare decision-making for specific groups or individuals, maximizing the likelihood of benefits and minimizing the risks associated with medical interventions [7, 19].

Big data radically alters this landscape. Through the integration of satellite imagery, electronic health records, genomic data, climate models, mobile phone metadata, social media signals, and other digital traces, researchers can now construct complex, dynamic, and high-dimensional models of health phenomena [20]. For example, in the study of dengue fever, predictive algorithms using meteorological data, urban density, and mobile phone geolocation have successfully anticipated outbreaks weeks in advance [9], a feat that would be difficult, if not impossible, using classical epidemiological tools alone.

This expansion of data sources holds profound methodological implications [16]. First, it challenges the traditional divide between “experimental” and “observational” evidence by introducing hybrid models that blend statistical rigor with real-world contextualization [16, 21]. Second, it demands new analytical competencies: data science, computational modeling, and causal inference from non-randomized data become essential to interpret findings meaningfully [16, 22]. And third, it reconfigures what we consider as internal validity, no longer defined merely by randomization and control, but also by the degree to which models account for the full spectrum of interacting factors influencing health outcomes [16, 21, 22].

From an investigative standpoint, this new paradigm offers a unique opportunity: to ask deeper questions and generate insights that are both granular and generalizable [21]. For diseases like schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, or Chagas, whose transmission is intricately linked to local geography, social vulnerability, and environmental change, the ability to incorporate satellite-based climate patterns, socioeconomic indicators, and patterns of population displacement into predictive models is not just a methodological upgrade; it is a scientific necessity (Figure 3) [23-25].

Figure 3 - Data ecosystem for artificial intelligence (AI)-driven personalized prediction models in neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) based on big data.

Figure 3 presents the conceptual framework for integrating heterogeneous and cross-disciplinary data sources to support AI-based predictive modeling in the context of NTDs. Unlike traditional models that rely on limited clinical or epidemiological parameters, this expanded ecosystem embraces a multidimensional perspective, incorporating real-time, molecular, environmental, behavioral, and systemic data layers. Key data domains include: clinical and biological inputs (e.g., clinical trajectories, diagnostics, panomics); vector and pathogen dynamics (e.g., host-pathogen interactions, vector ecology); environmental and planetary health factors (e.g., land use, climate, biodiversity); and sociocultural and systemic determinants (e.g., mobility, cultural practices, health system capacity). These variables feed into dynamic, adaptive models that can anticipate disease emergence, progression, and response at an individualized level, accounting for complex interactions that were previously unmeasurable within the conventional evidence-based medicine framework.

Practically, the integration of big data into EBM is already transforming public health strategies [21, 22]. Early warning systems for vector-borne diseases, AI-assisted clinical decision support tools, and real-time outbreak monitoring dashboards are being piloted in diverse settings (Figure 3) [26]. However, their widespread implementation remains uneven, constrained by infrastructural gaps, data governance challenges, and a lack of consensus about how to validate and trust these new forms of evidence [21, 22].

This is why the conceptual shift in the EBM pyramid is so critical. By formally recognizing the value of big data and computational evidence, we open the door to more inclusive, adaptive, and context-aware forms of health science [7]. This evolution is particularly urgent for NTDs and underserved populations, whose realities often escape the narrow lens of traditional research protocols [9-13].

In essence, big data does not aim to replace classical evidence, but to complete it, by capturing what was previously invisible, modeling what was previously intractable, and empowering decision-makers with tools that are more responsive to complexity and uncertainty. As this new evidence ecosystem unfolds, the scientific community must be ready not only to harness its power but to redefine what we mean by high-quality and actionable evidence in the 21st century.

CURRENT GAPS, LIMITATIONS, AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE INTERSECTION BETWEEN BIG DATA AND NTDS

In a time when health challenges are becoming increasingly complex, data-intensive, and context-dependent, the capacity to generate evidence that is both relevant and actionable has never been more critical [14, 15]. Yet, the scientific system still struggles to align its knowledge production with the actual burden of disease, particularly in the case of NTDs, which continue to affect millions in the world’s most vulnerable regions [4, 18, 27].

To better understand the current research landscape and its blind spots, we turned to bibliometric analysis, a method that, serves as a valuable proxy for identifying research trends and knowledge gaps [14]. Scientific publications, when aggregated, categorized, and tracked over time, can reveal which topics dominate academic attention and which remain marginalized, regardless of their epidemiological or societal relevance [14].

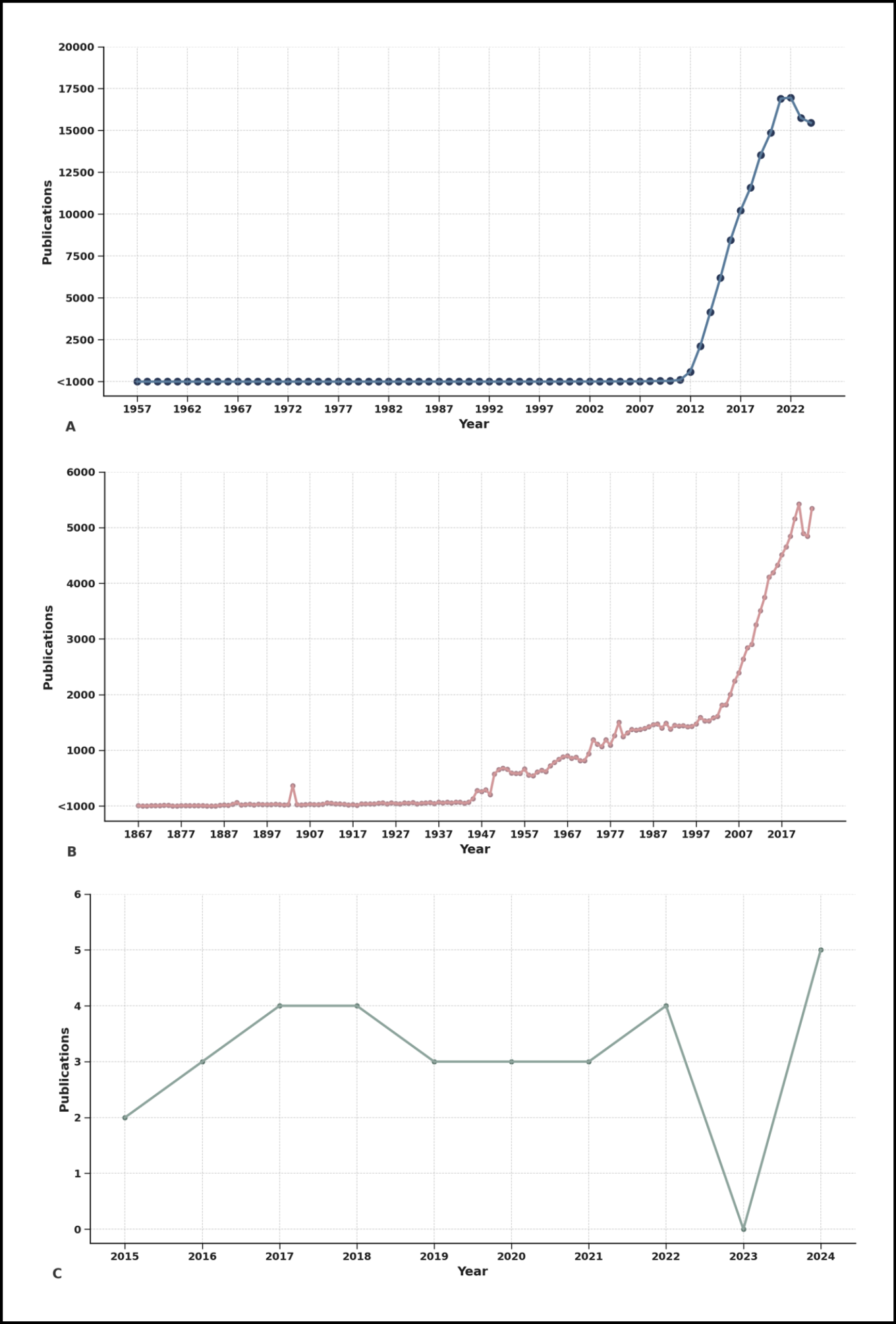

Using a comparative analysis of publication frequencies from up to 2024 in Scopus database, we examined the trajectory of three critical knowledge domains:

1) Big Data (Figure 4A);

2) NTDs (Figure 4B); and

3) Big Data applied to NTDs (Figure 4C).

Figure 4 - Global trends in scientific publications on big data, neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), and their intersection.

This figure illustrates the temporal evolution in the volume of scientific publications from Scopus databases. Panel A shows the exponential rise in publications related to Big Data, especially after 2010, reflecting its widespread global adoption. Panel B presents the historical trajectory of publications on NTDs, evidencing steady but less prominent growth, particularly since the early 2000s. In stark contrast, panel C highlights the limited number of publications that integrate both Big Data and NTDs, with fewer than six publications per year and an almost negligible presence before 2015. These disparities underline a critical research gap and the missed opportunity to harness data-intensive technologies for diseases that disproportionately affect the world’s poorest populations.

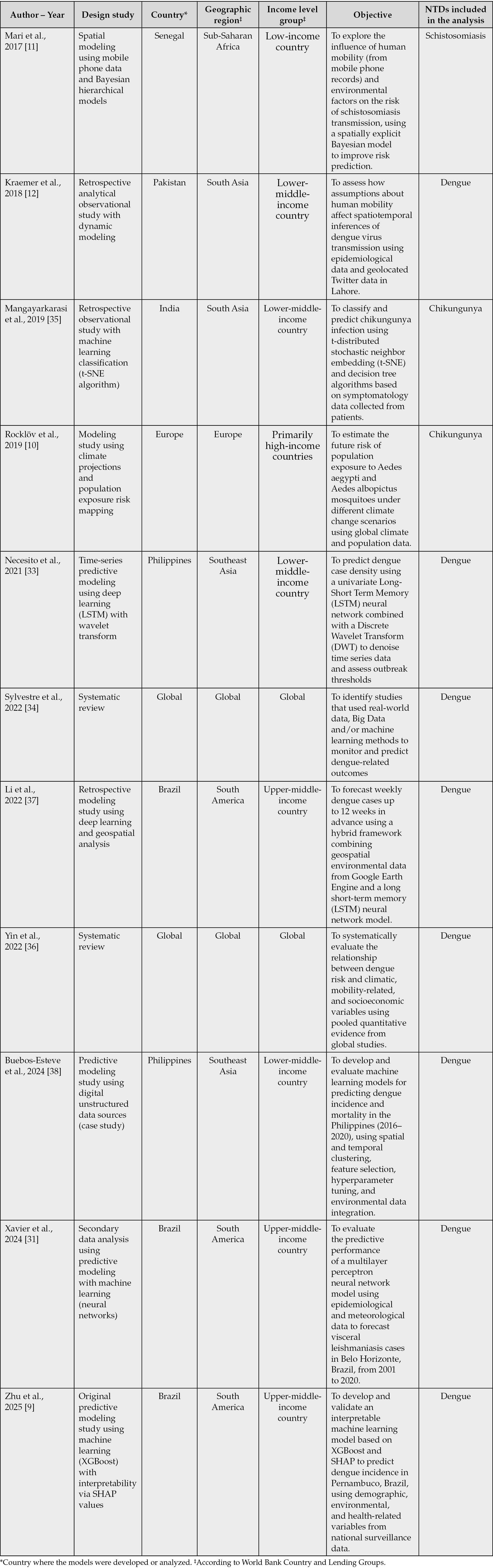

The search strategy was constructed from MeSH terms as well as synonyms. The search was reproduced on August 4, 2025. No exclusion criteria were applied, except in the case of publications on Big Data and NTDs, for which a subanalysis was conducted to characterize the available evidence on this topic to date, as detailed in Table 1. For the selection of studies included in Table 1, only original articles presenting primary data or systematic reviews were considered. Due to the small number of results, the documents were manually reviewed by two authors to verify that they were directly related to the topic of interest.

Table 1 - Summary of original studies and systematic reviews using big data for NTDs research.

The findings are as revealing as they are concerning (Figure 4). Publications on Big Data have experienced exponential growth over the last two decades (Figure 4A), reflecting its widespread application in areas such as finance, cybersecurity, marketing, and, more recently, healthcare [28]. Parallel to this, research on NTDs has shown a modest but steady increase (Figure 4B), likely driven by global health campaigns and donor interest in diseases like dengue, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, and schistosomiasis [4].

However, the number of publications that explicitly integrate both Big Data and NTDs remains startlingly low (Figure 4C). Despite the theoretical and practical potential of big data to improve disease prediction, outbreak surveillance, and health system responses in NTDs-endemic regions, the intersection of these fields has been largely underexplored and underfunded [2, 4].

This disparity is not merely academic; it has profound ethical and public health implications. As highlighted by Evans et al., global research output often correlates poorly with local disease burdens, reinforcing patterns of scientific inequity [29]. Countries with high NTDs prevalence are frequently those with the lowest capacity to produce or influence scientific narratives [4]. When new technologies like big data are developed primarily in high-income settings and remain disconnected from the realities of LMICs, a dangerous epistemic divide emerges: one where the tools of the future fail to serve the populations that need them most [4].

Moreover, as AbouZahr and colleagues argue, traditional population health metrics often fail to reflect the structural determinants and systemic biases that shape health outcomes [30]. Without integrating socio-environmental, climatic, and behavioral variables, many of which can be captured through big data, it becomes difficult to develop predictive models that are both accurate and context-sensitive [30].

Therefore, the lack of integration between big data methodologies and NTDs-focused research represents more than a technological delay, it is a missed opportunity to revolutionize how we understand and act upon some of the most persistent and neglected health threats on the planet.

But within this gap lies a critical opportunity: to reshape the research agenda and bridge the digital divide in health innovation. By encouraging interdisciplinary collaborations, investing in local data infrastructures, and aligning funding priorities with global disease burdens, the scientific community can begin to reverse this imbalance. In doing so, we can move toward a more equitable and impactful model of evidence generation, one that does not merely reflect scientific trends, but actively responds to global health needs [15, 27].

CHARACTERISTICS AND SCOPE OF AVAILABLE AND APPLICABLE SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE ON BIG DATA AND NTDS

Despite the exponential growth of scientific publications on Big Data and, to a lesser extent, on NTDs, the intersection of both fields remains embryonic. Our systematic search in Scopus identified only 33 publications in this field, from which a rigorous manual review yielded a final sample of 12 original/secondary data studies that directly employed Big Data approaches to generate predictive, explanatory, or analytical models for NTDs, or synthesized evidence via systematic reviews following PRISMA methodology (Table 1). This limited corpus is in itself indicative of the magnitude of the research gap.

The included studies varied significantly in terms of disease focus, geographic scope, methodological complexity, and data sources. For instance, Zhu et al. and Xavier et al. centered on dengue in Brazil, leveraging environmental, climatic, and spatial data through cloud-based platforms and clustering algorithms to construct large-scale geospatial datasets [9, 31]. These approaches showcased the value of integrating high-volume and high-variety datasets for predicting disease hotspots, although they still relied heavily on secondary data sources with varying degrees of resolution and quality [9, 31].

Other studies, such as Wahed Chowdhury et al. and Necesito et al., also focused on dengue, incorporating satellite imagery, climatic indicators, and spatio-temporal modeling to detect patterns of disease transmission [32, 33]. While they demonstrate the growing sophistication in data integration and modeling, these efforts remain largely localized, often constrained by data availability, standardization challenges, or lack of longitudinal validation [32, 33].

Several works attempted to build predictive models through machine learning and deep learning techniques for diseases such as Dengue and Chikungunya [34, 35]. However, most of these models were trained on relatively small datasets or lacked robust external validation. Moreover, many failed to integrate critical social or behavioral determinants of disease, which are increasingly recognized as key in the new generation of evidence-based health models.

A few reviews explored the role of digital epidemiology and mobility data in vector-borne disease control, hinting at the future potential of data-rich platforms such as mobile phone records, social media, or participatory surveillance [11, 12]. Yet, the absence of actionable implementation pathways and the limited inclusion of health system capacity indicators weaken their practical utility.

Most notably, very few studies engaged in deep multivariate modeling or incorporated structural, environmental, climatic, and systemic variables simultaneously, a critical shortcoming considering the complexity of NTDs transmission dynamics [10,36-38]. There is also a noticeable underutilization of Big Data infrastructures such as cloud-based computing, federated learning, or multi-source harmonization frameworks, which are central to the new paradigm of high-validity health evidence [13].

This body of literature, though modest in size and methodological designs, clearly reflects a field in early development. Conceptually, the studies demonstrate an emerging but fragmented understanding of how to leverage Big Data for NTDs. Methodologically, they reveal limitations in data integration, interoperability, and generalizability. And strategically, they underscore the urgency of advancing from isolated predictive tasks toward comprehensive, adaptive, and equity-oriented models that can inform local and regional decision-making in high-burden contexts [3, 4, 8].

Taken together, the findings from this systematic mapping reveal a promising but underexploited research frontier. To move beyond proof-of-concept models and small-scale pilots, future work must embrace the complexity of NTD epidemiology within a planetary health framework [26], leveraging Big Data not only for prediction but for prevention, intervention optimization, and long-term surveillance [39].

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Despite the exponential growth of research in both Big Data analytics and NTDs as independent scientific domains, our findings reveal a substantial and persistent gap at their intersection. The bibliometric disparity previously described is not merely a quantitative observation, it reflects a deeper structural issue in global research priorities, where the populations most affected by NTDs remain largely excluded from the benefits of data-driven innovation [4]. This imbalance not only limits scientific progress but also perpetuates inequities in health outcomes and access to actionable evidence [40-42].

Although dengue currently dominates the available literature on Big Data and NTDs, this should not lead us to assume that predictive learning models are limited to this disease. The same principles can and should be extended to other conditions with different transmission dynamics and data constraints [43, 44]. For instance, Chagas disease could benefit from incorporating housing characteristics, mobility patterns, and blood-bank records; leishmaniasis requires attention to land-use change, vector ecology, and animal reservoirs; and schistosomiasis is closely tied to freshwater exposure and sanitation infrastructure [43, 44]. Even soil-transmitted helminths, often overlooked in data science, could be modelled using school mapping, climate variables; and water, sanitation, and hygiene indicators [43, 44].

Each of these examples illustrates how predictive frameworks can be adapted, drawing on locally available data and pragmatic proxies, so that the tools of Big Data evolve to reflect the specific realities of diverse NTDs rather than remaining narrowly focused on dengue alone. Then, diversifying agendas requires targeted funding mechanisms, explicit calls for proposals, and collaborative platforms that prioritize underrepresented conditions.

The set of studies included in this review, while modest in number, offers critical insight into the current capabilities and limitations of integrating Big Data approaches with NTDs research. Most of these studies were conducted in LMICs, particularly Brazil, the Philippines, and parts of South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, which aligns with the geographical burden of NTDs. However, there is a narrow concentration of focus on dengue, with far fewer applications addressing other high-burden conditions such as Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, or helminth infections [2]. This signals the need for a broader epidemiological scope.

From a methodological standpoint, the use of machine learning, hybrid predictive frameworks, and model optimization techniques is promising. However, these efforts frequently face constraints such as limited sample sizes, reliance on single-source data, minimal integration of social or environmental determinants, and lack of transparency regarding model interpretability [16]. Furthermore, few studies demonstrated reproducibility or standardization of modeling pipelines, and only two systematic reviews were identified, both exclusively targeting dengue, indicating a lack of robust knowledge synthesis across diseases or modeling approaches.

In light of the evolving paradigm of EBM, which increasingly integrates high-dimensional data, AI, and continuous learning systems, several opportunities emerge [7]. Future research should actively expand the range of NTDs studied, moving beyond dengue to include neglected conditions with severe public health consequences. It is also critical to improve the interpretability and transparency of predictive models, ensuring that AI serves not only accuracy but also clinical relevance and policy utility [41-46]. Integrating heterogeneous data sources, including environmental, behavioral, demographic, and real-time surveillance inputs, can greatly enhance the contextual validity of predictions [21].

Additionally, global equity must be placed at the center of future agendas, promoting funding mechanisms and collaborative infrastructures that empower institutions in low-resource settings to lead data science innovations tailored to their realities [47-48]. Finally, establishing reproducible and standardized machine learning workflows will be vital for ensuring that research outputs are scalable, comparable, and aligned with open science principles [21].

Ultimately, bridging the current divide between Big Data and NTDs research will require more than technological advancement, it will demand a shift in epistemological frameworks, investment priorities, and ethical commitments. The new generation of the EBM pyramid offers a conceptual and practical platform to advance this integration [7]. Aligning data-driven methodologies with the complexity of NTDs is not only a scientific opportunity but also a public health imperative.

The future application of Big Data in NTD research will only be meaningful if it is accompanied by a strong commitment to governance and equity [21, 47, 48]. This means ensuring that the data generated in endemic regions are not simply extracted for external analysis but remain under the stewardship of local institutions, with fair access for the communities and researchers who produce them [47, 48]. Equitable models of governance should prioritize local ownership, transparent agreements on data sharing, and mechanisms for benefit distribution, such as co-authorship, training, and infrastructure transfer. In addition, ethical frameworks must guarantee privacy protection and compliance with national regulations, while being sensitive to cultural expectations [21, 47]. Only by embedding equity into the design and use of predictive models can Big Data approaches avoid reproducing historical patterns of neglect and instead serve as tools that genuinely advance health justice in endemic regions.

A major challenge in the field is the limited reproducibility of current predictive models, largely due to heterogeneous methods, scarce validation, and the absence of shared pipelines. Strengthening reproducibility requires more than technical adjustments; it calls for a cultural shift towards openness and transparency [39, 41, 42]. Even in resource-constrained settings, it is possible to adopt simple but powerful practices, such as documenting model assumptions, making codes and workflows openly available, and using clear data dictionaries [39, 41, 42]. Efforts should also include external validation across different timeframes and regions, so that models are not only accurate but also transferable to other contexts.

This review is limited by the inherently descriptive nature of scientometrics and narrative synthesis approaches, which restricts the ability to draw causal inferences or generalize findings beyond the analyzed literature. The inclusion criteria, focused exclusively on original studies employing primary or secondary data and systematic reviews, may have excluded exploratory or conceptual works with emerging relevance. Additionally, variations in terminology, inconsistent reporting of methods, and the lack of standardized frameworks for defining Big Data applications in NTDs may have led to the underrepresentation of relevant studies. The reliance on Scopus as a single database may have excluded relevant records indexed elsewhere. Moreover, language restrictions and the predominance of English-language publications may bias coverage toward specific regions. These limitations underscore the need for future meta-research employing more systematic and inferential methodologies to better map the scope and impact of this emerging field.

CONCLUSIONS

The analysis revealed a pronounced asymmetry between the independent growth of scientific production in Big Data and NTDs, and the minimal integration of both fields. Despite the pressing need for innovative solutions, the application of advanced data science methodologies to NTDs research has remained limited, concentrated on a small number of diseases, and geographically uneven.

From the empirical review, it was observed that only a small set of original studies and systematic reviews have effectively applied Big Data approaches to the prediction and understanding of NTDs. Although technically promising, these efforts have been constrained by methodological heterogeneity, lack of reproducibility, a narrow disease focus (primarily dengue), and limited inclusion of social, environmental, and behavioral determinants of health.

Nonetheless, these limitations reflect an opportunity for transformation. The emergence of a new generation of EBM, characterized by multidimensional data integration, continuous learning, and AI-enhanced inference, has redefined the criteria for valid evidence and its beneficiaries. When responsibly implemented, Big Data methodologies have the potential to uncover complex patterns of disease risk, improve resource allocation, and support context-specific responses in regions traditionally excluded from biomedical innovation.

A central element for the future success of Big Data in NTDs is the active leadership of local research institutions. Adoption alone is not enough; approaches must be co-designed, implemented, and adapted by institutions working in endemic regions. This implies involving local scientists in framing the research questions, curating and governing data, and guiding the methodological choices that ensure contextual validity. It also requires embedding predictive models into national surveillance systems and health programs, with training opportunities that build technical capacity and prevent dependency on external expertise. In this way, Big Data becomes not only a scientific tool but also an instrument of empowerment, fostering sustainability and ensuring that innovations are shaped by and for the communities most affected.

To address the equity gap in global health research, it is necessary not only to expand the volume of data but also to ensure the alignment of scientific priorities with the needs of populations most affected by NTDs. The findings of this analysis emphasize the need to reconfigure the epistemological foundation of medical evidence, positioning Big Data as a central element in the generation of actionable, inclusive, and contextually relevant knowledge. In doing so, the prioritization of NTDs in global health agendas may be advanced, promoting a more just and responsive scientific landscape.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

REFERENCES

[1] World Health Organization. Global report on neglected tropical diseases 2024. Available at: https://www.who.int/teams/control-of-neglected-tropical-diseases/global-report-on-neglected-tropical-diseases-2024 (Accessed 25 Jul 2025).

[2] Stolk WA, Kulik MC, le Rutte EA, et al. Between-Country Inequalities in the Neglected Tropical Disease Burden in 1990 and 2010, with Projections for 2020. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016; 10(5): e0004560.

[3] Bhakuni H, Abimbola S. Epistemic injustice in academic global health. Lancet Glob Health. 2021; 9(10): e1465-e1470.

[4] Donadeu M, Gyorkos TW, Horstick O, et al. Tracking progress along the WHO Neglected Tropical Diseases Road Map to 2030: A guide to the Gap Assessment Tool (GAT) and results from the 2023-2024 assessment. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2025; 19(7): e0013194.

[5] Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, Alahdab F. New evidence pyramid. Evid Based Med. 2016; 21(4): 125-127.

[6] Tirupakuzhi Vijayaraghavan BK, Gupta E, Ramakrishnan N, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the conduct of critical care research in low and lower-middle income countries: A scoping review. PLoS One. 2022; 17(5): e0266836.

[7] Subbiah V. The next generation of evidence-based medicine. Nat Med. 2023; 29(1): 49-58.

[8] Bhopal A, Callender T, Knox AF, Regmi S. Strength in numbers? Grouping, fund allocation and coordination amongst the neglected tropical diseases. J Glob Health. 2013; 3(2): 020302.

[9] Zhu Q, Li Z, Dong J, et al. Spatiotemporal dataset of dengue influencing factors in Brazil based on geospatial big data cloud computing. Sci Data. 2025; 12(1): 712.

[10] Rocklöv J, Tozan Y, Ramadona A, et al. Using Big Data to Monitor the Introduction and Spread of Chikungunya, Europe, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019; 25(6):1041-1049.

[11] Mari L, Gatto M, Ciddio M, et al. Big-data-driven modeling unveils country-wide drivers of endemic schistosomiasis. Sci Rep. 2017; 7(1): 489.

[12] Kraemer MUG, Bisanzio D, Reiner RC, et al. Inferences about spatiotemporal variation in dengue virus transmission are sensitive to assumptions about human mobility: a case study using geolocated tweets from Lahore, Pakistan. EPJ Data Sci. 2018; 7(1): 16.

[13] Amusa LB, Twinomurinzi H, Phalane E, Phaswana-Mafuya RN. Big Data and Infectious Disease Epidemiology: Bibliometric Analysis and Research Agenda. Interact J Med Res. 2023; 12: e42292.

[14] Lozada-Martinez ID, Hernandez-Paez D, Zárate YEJ, Delgado P. Scientometrics and meta-research in medical research: approaches required to ensure scientific rigor in an era of massive low-quality research. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2025; 71(4): e20241612.

[15] Lozada-Martinez ID, Neira-Rodado D, Martinez-Guevara D, Cruz-Soto HS, Sanchez-Echeverry MP, Liscano Y. Why is it important to implement meta-research in universities and institutes with medical research activities? Front Res Metr Anal. 2025; 10: 1497280.

[16] Caliebe A, Leverkus F, Antes G, Krawczak M. Does big data require a methodological change in medical research? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019; 19(1): 125.

[17] King VJ, Nussbaumer-Streit B, Shaw E, et al. Rapid reviews methods series: con-siderations and recommendations for evidence synthesis in rapid reviews. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2024; 29(6): 419-422.

[18] Boelaert M; NIDIAG Consortium. Clinical Research on Neglected Tropical Diseases: Challenges and Solutions. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016; 10(11): e0004853.

[19] Chen YM, Hsiao TH, Lin CH, Fann YC. Unlocking precision medicine: clinical applications of integrating health records, genetics, and immunology through artificial intelligence. J Biomed Sci. 2025; 32(1): 16.

[20] Batko K, Ślęzak A. The use of Big Data Analytics in healthcare. J Big Data. 2022; 9(1): 3.

[21] Hulsen T, Jamuar SS, Moody AR, et al. From Big Data to Precision Medicine. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019; 6: 34.

[22] Wang L, Alexander CA. Big data analytics in medical engineering and healthcare: methods, advances and challenges. J Med Eng Technol. 2020; 44(6): 267-283.

[23] Chen Y, Luo F, Martinez L, Jiang S, Shen Y. Identifying key aspects to enhance predictive modeling for early identification of schistosomiasis hotspots to guide mass drug administration. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2025; 19(7): e0013315.

[24] Saadene Y, Salhi A. Spatio-temporal modeling of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis under climate change scenarios in the Maghreb region (2021-2100). Acta Trop. 2025; 263: 107548.

[25] Ledien J, Cucunubá ZM, Parra-Henao G, et al. Linear and Machine Learning modelling for spatiotemporal disease predictions: Force-of-Infection of Chagas disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022; 16(7): e0010594.

[26] Pfenning-Butterworth A, Buckley LB, Drake JM, et al. Interconnecting global threats: climate change, biodiversity loss, and infectious diseases. Lancet Planet Health. 2024; 8(4): e270-e283.

[27] Lozada-Martinez ID, Lozada-Martinez LM, Fiorillo-Moreno O. Leiden manifesto and evidence-based research: Are the appropriate standards being used for the correct evaluation of pluralism, gaps and relevance in medical research? J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2024; 54(1): 4-6.

[28] Parlina A, Ramli K, Murfi H. Theme Mapping and Bibliometrics Analysis of One Decade of Big Data Research in the Scopus Database. Information. 2020; 11(2): 69.

[29] Evans JA, Shim JM, Ioannidis JP. Attention to local health burden and the global disparity of health research. PLoS One. 2014; 9(4): e90147.

[30] AbouZahr C, Boerma T, Hogan D. Global estimates of country health indicators: useful, unnecessary, inevitable? Glob Health Action. 2017; 10(sup1): 1290370.

[31] Xavier F, Barbosa GL, Marques CCA, Saraiva AM. Big Data-Planetary Health approach for evaluating the Brazilian Dengue Control Program. Rev Saude Publica. 2024; 58: 17.

[32] Chowdhury MAW, Müller J, Ghose A, et al. Combining species distribution models and big datasets may provide finer assessments of snakebite impacts. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024; 18(5): e0012161.

[33] Necesito IV, Velasco JM, Kwak J, et al. Combination of univariate long-short term memory network and wavelet transform for predicting dengue case density in the national capital region, the Philippines. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2021; 52(4): 479-494.

[34] Sylvestre E, Joachim C, Cécilia-Joseph E, et al. Data-driven methods for dengue prediction and surveillance using real-world and Big Data: A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022; 16(1): e0010056.

[35] Mangayarkarasi M, Jamunadevi C, Balasubramanie P. Pos and neg classified using Chikungunya symptoms through big data analytics. Int J Sci Technol Res. 2019; 8(12): 652-655.

[36] Yin S, Ren C, Shi Y, Hua J, Yuan HY, Tian LW. A Systematic Review on Modeling Methods and Influential Factors for Mapping Dengue-Related Risk in Urban Settings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(22): 15265.

[37] Li Z, Gurgel H, Xu L, Yang L, Dong J. Improving Dengue Forecasts by Using Geospatial Big Data Analysis in Google Earth Engine and the Historical Dengue Information-Aided Long Short Term Memory Modeling. Biology (Basel). 2022; 11(2): 169.

[38] Buebos-Esteve DE, Dagamac NHA. Spatiotemporal models of dengue epidemiology in the Philippines: Integrating remote sensing and interpretable machine learning. Acta Trop. 2024; 255: 107225.

[39] Dolley S. Big Data’s Role in Precision Public Health. Front Public Health. 2018; 6: 68.

[40] Lozada-Martinez ID, Fiorillo-Moreno O, Hernández-Paez DA, Bermúdez V. Clinical trials on medical errors need to strengthen geographical representation, methodological and reporting quality. QJM. 2025; 12: hcaf068.

[41] Han H. Challenges of reproducible AI in biomedical data science. BMC Med Genomics. 2025; 18(Suppl 1): 8.

[42] Haibe-Kains B, Adam GA, Hosny A, Khodakarami F, Waldron L, Wang B, et al. Transparency and reproducibility in artificial intelligence. Nature. 2020; 586(7829): E14-E16.

[43] Coulibaly JT, Hürlimann E, Patel C, et al. Optimizing Implementation of Preventive Chemotherapy against Soil-Transmitted Helminthiasis and Intestinal Schistosomiasis Using High-Resolution Data: Field-Based Experiences from Côte d’Ivoire. Diseases. 2022; 10(4): 66.

[44] Soundrapandiyan R, Manickam A, Akhloufi M, Srinivasa Murthy YV, Meenakshi Sundaram RD, Thirugnanasambandam S. An Efficient COVID-19 Mortality Risk Prediction Model Using Deep Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique and Convolution Neural Networks. BioMedInformatics. 2023; 3(2): 339-368.

[45] Leung CK. Biomedical Informatics: State of the Art, Challenges, and Opportunities. BioMedInformatics. 2024; 4(1): 89-97.

[46] de Brevern AG. BioMedInformatics, the Link between Biomedical Informatics, Biology and Computational Medicine. BioMedInformatics. 2024; 4(1): 1-7.

[47] Ortega-Caballero M, Gonzalez-Vazquez MC, Hernández-Espinosa MA, Carabarin-Lima A, Mendez-Albores A. The Impact of Environmental and Housing Factors on the Distribution of Triatominae (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) in an Endemic Area of Chagas Disease in Puebla, Mexico. Diseases. 2024; 12(10): 238

[48] Vicar EK, Simpson SV, Mensah GI, Addo KK, Donkor ES. Yaws in Africa: Past, Present and Future. Diseases. 2025; 13(1): 14.