Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 1, 52-60, 2024

doi: 10.53854/liim-3201-7

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Seroprevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis and associated risk factors among HIV positive women in North Central Nigeria

Pius Omoruyi Omosigho1, Tope Elizabeth Ajide2, Osazee Ekundayo Izevbuwa3, Olalekan John Okesanya4, Janet Mosunmola Oladejo5, Paulinus Osarodion Uyigue6

1Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Faculty of Applied Health Sciences, Edo State University, Uzairue, Nigeria;

2Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Faculty of Pure and Applied Science, Kwara State University, Malete, Nigeria;

3Department of Medical Laboratory Science, College of Health Sciences, Igbinedion University, Okada, Nigeria;

4Department of Public Health and Maritime Transport, University of Thessaly, Volos, Greece;

5Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Kwara State, Nigeria;

6Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Achievers University, Owo, Nigeria

Received 17 August 2023; accepted 8 January 2024

Corresponding author

Pius Omoruyi Omosigho

E-mail: omosigho.omoruyi@edouniversty.edu.ng

SummaRY

Introduction: Chlamydia trachomatis infection is among the STDs that are known to increase the risk of HIV infection. The present study aims to determine the seroprevalence of C. trachomatis among HIV positive women in Ilorin and Offa, Kwara State, North Central Nigeria.

Methods: Serum samples from 400 HIV positive women attending the HAART Clinic in Offa and the Ilorin General Hospital in Kwara State, Nigeria, were screened using Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), utilizing the immunocomb Chlamydia IgG test kit (Calbiotech, El Cajon, CA, USA) to check for the existence of anti-C. trachomatis antibodies.

Result: Anti-C. trachomatis antibodies were present in 92 (23.0%) of the 400 HIV positive women samples. There was a higher prevalence among the age group 36-40 years. Hence, age groupings were statistically and significantly associated (p=0.001) with the seroprevalence of C. trachomatis among HIV positive women. Married HIV positive women (60.9%) had the highest prevalence of C. trachomatis, with a statistically significant association (p=0.001). There was a statistically significant association between the number of sexual partner(s) (p=0.001) and the seroprevalence of C. trachomatis among HIV positive women.

Conclusions: The high frequency confirms the necessity for comprehensive sexual education among young adults and routine testing for anti-C. trachomatis. It reflects the endemicity of the infection in Ilorin and Offa Kwara State, Nigeria.

Keywords: Seroprevalence, Chlamydia trachomatis, HIV positive women, associated risk factors, Ilorin-Offa.

INTRODUCTION

Chlamydia trachomatis is a Gram-negative, non-motile, intracellular bacteria that was initially thought to belong to the Rickettsia kingdom [1]. It needs an exogenous source of high energy substances because it lacks the metabolic capacity to manufacture ATP. It is known as an energy parasite because of this. It goes through a special biphasic developmental cycle and develops recognizable intracellular inclusions that allow for identification via light or fluorescence microscopy [2]. More than half of the nearly one million C. trachomatis infections among sexually active young people aged 15 to 25 reported worldwide by the USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were female [3]. According to reports from Nigeria, prevalence rates for both pregnant and non-pregnant women, as well as their spouses, ranged from 38% to 51% [4]. Though there are reports of a lower occurrence in developed nations like Italy (6.3%) and North India (19.9%) [5]. The clinical features of chlamydial infection are nonspecific and usually asymptomatic in about 80% of women [6]. About one-third of those with symptoms will present with dyspareunia, post-coital bleeding and intermenstrual bleeding, and/or vaginal discharge, which also includes mucopurulent cervical discharge that appears yellow on a white cotton-tipped swab, cervical ectopy, cervical edema, and cervical friability [5]. C. trachomatis also causes acute urogenital infections that can lead to persistent infections, which may initiate a pathogenic process that results in chronic diseases like arthritis in a genetically predisposed individual, ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, and tubal factor infertility [7].

A wide range of medications, especially tetracyclines and macrolides, are effective against C. trachomatis. Beta-lactams like penicillin lack the bactericidal effect against chlamydial germs because their cell wall is distinct from that of many bacteria [8]. The urogenital tract illness, inclusion conjunctivitis, trachoma, and lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is all caused by C. trachomatis [9]. Risk factors that have been found to be associated with this type of infection include age under 25 years, multiple sexual partners, use of oral contraceptives, and failure to use barrier methods of contraception. Others include a history of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), cervical ectopy, low socioeconomic status, HIV seropositivity, and seroconversion [10, 11].

HIV acquisition, transmission, and infectivity are facilitated by other STIs which can operate as co-factors through a variety of immunological and biological routes” [12]. HIV and C. trachomatis infections share the urogenital tract as a portal of entry and have mutually beneficial effects. When C. trachomatis invades, it causes genital epithelium destruction by an enzymatic activity that makes HIV infection easier [13]. HIV suppresses the immune system by killing CD4+ cells and preventing T-cell activation [14]. The detection of the epitopes found in the C. trachomatis omp1 variable domain by T-cells is crucial for determining the severity of the infection in immunosuppressed people [15]. In addition to sharing similar social practices that promote sexual transmission, all STIs and the two diseases share a biological connection [16].

Both sexes continue to exhibit no symptoms of C. trachomatis infection, which makes it difficult to diagnose and treat for lengthy periods of time [17]. In many African nations, where awareness of the disease is extremely poor and there are few facilities for its routine diagnosis, the situation may be more serious. Thus, C. trachomatis infections may have a significant negative impact on both health and the economy. As a result, the goal of this study is to ascertain the seroprevalence of C. trachomatis among women in Ilorin and Offa North Central, Kwara State, who are HIV positive.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design and settings

A simple random sampling technique was designed to select our study participants attending the HAART clinic at the University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital and General Hospital Offa, Kwara State, between September 2021 and February 2022. Kwara is one of Nigeria’s 36 states, located in the west of Nigeria. The inclusion criteria included all consented women aged 18-45 years who were HIV positive and attended both the HAART clinic at the University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital and General Hospital Offa in Kwara State, Nigeria. This study maximized a semi-structured interviewer-administered questionnaire that was compiled from reviews of relevant literature and previous research. Fifty questionnaires were randomly administered to representatives of the study participants. This was done to pretest and evaluate the survey format and identify its strengths and weaknesses. A total of four hundred (400) participants were recruited for this study. The study participants consisted of HIV positive women attending HAART clinics in Ilorin and Offa North Central, Kwara State. Five final-year Medical Laboratory Science and Public Health students who were research assistants were properly trained. A semi-structured administered questionnaire used in the course of the study was developed from a review of relevant literature and prior research. The questionnaire was written in English, and variables including age, marital status, educational level, type of occupation, and residence type were included in the questionnaire.

Ethical considerations

Permission to carry out the study was first approved by the Department of Medical Laboratory Science at Kwara State University, Nigeria. Clearance and ethical approval were collected from the Ministry of Health, Ilorin, and Kwara State with the reference number MOH/KS/EU/777/558 and submitted to the Medical Director, University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, and General Hospital Offa for their approval before the commencement of the study. Prior to data collection, informed consent was obtained from each participant individually after being notified that their information would be treated with the highest level of confidentiality and used solely for the study. The study closely adhered to ethical standards, and participation was voluntary.

Sample collection and laboratory analysis

Five mL of blood was collected using an appropriate sterile syringe from the prominent vein of consented participants at the donor bay. The blood samples were collected into plain bottles and transported to the laboratory. The blood samples were spun, and the serum was used to screen for HIV, followed by Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to demonstrate the presence of anti-Chlamydia antibodies in the serum of the participants.

Informed consent was obtained prior to HIV testing at the HAART clinics, followed by the diagnosis of HIV infection. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, two distinct rapid test kits-STAT-PAK (Chembio Diagnostics Systems, Inc 3661, Horseblock Rd, Medford, NY 11763) and Determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo (Abbott Diagnostics) - were utilized to detect HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies.

On the day of the examination, all serum samples were delivered to the Microbiology Laboratory, Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Kwara State University, after being stored at respective HAART clinics and frozen at -80°C. An Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent assay method (ELISA, Calbiotech, El Cajon, CA, USA) was used to detect the IgG antibody to C. trachomatis according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Data analysis

The data obtained was screened for error and completeness. Analysis was conducted in accordance with the study aim and objective using IBM-SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics of frequency counts and simple percentages were summarized and presented in tables. Chi square test was employed to check the associations between both the outcome and the independent variables at a p-value of <0.05.

Consent of human subject protection

Identifying information, such as names, was not included in the questionnaire. The collected data was encrypted and stored in a different file to ensure high confidentiality, which can only be accessed by authorized personnel for management and logistic purposes.

RESULTS

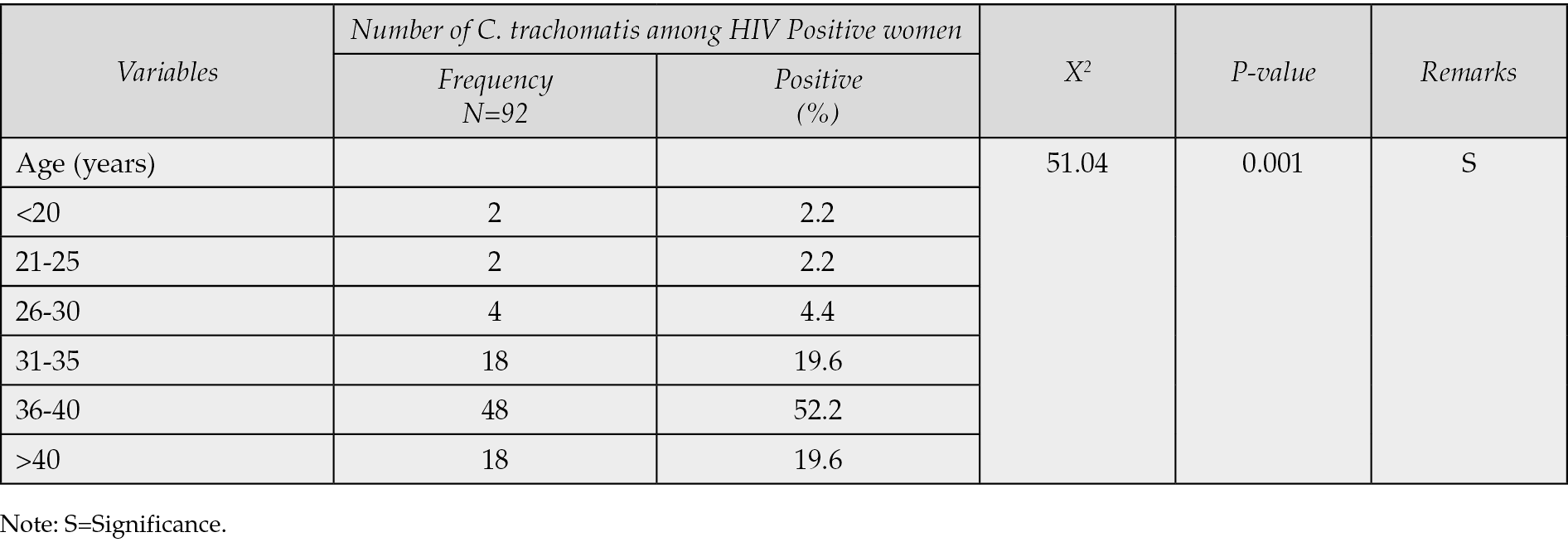

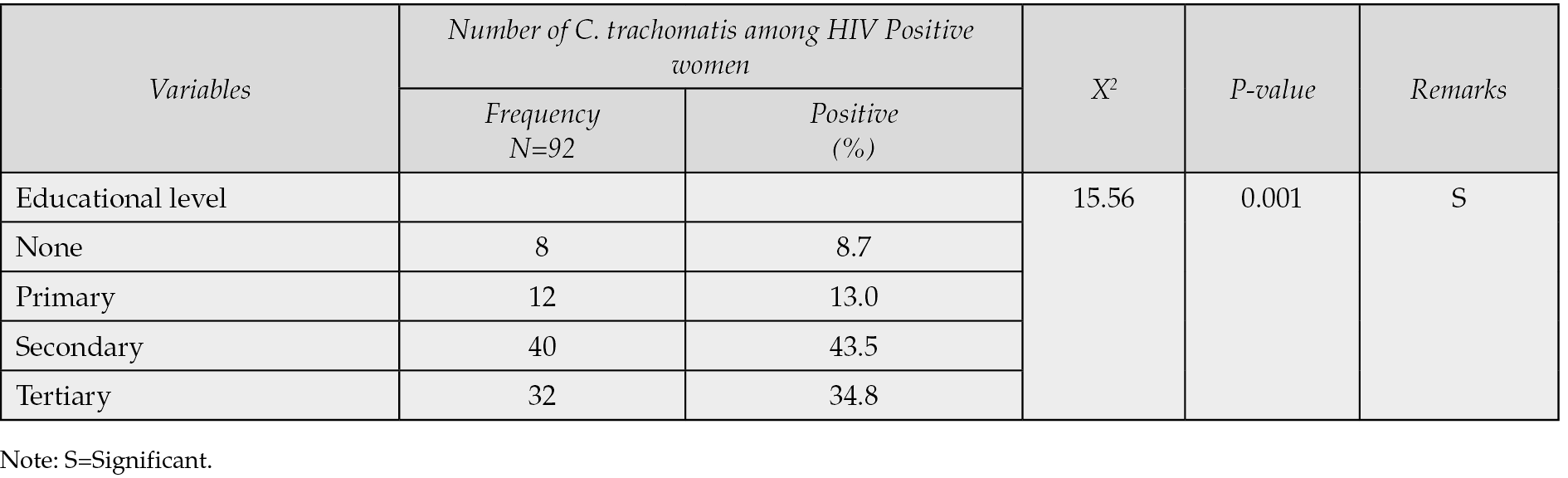

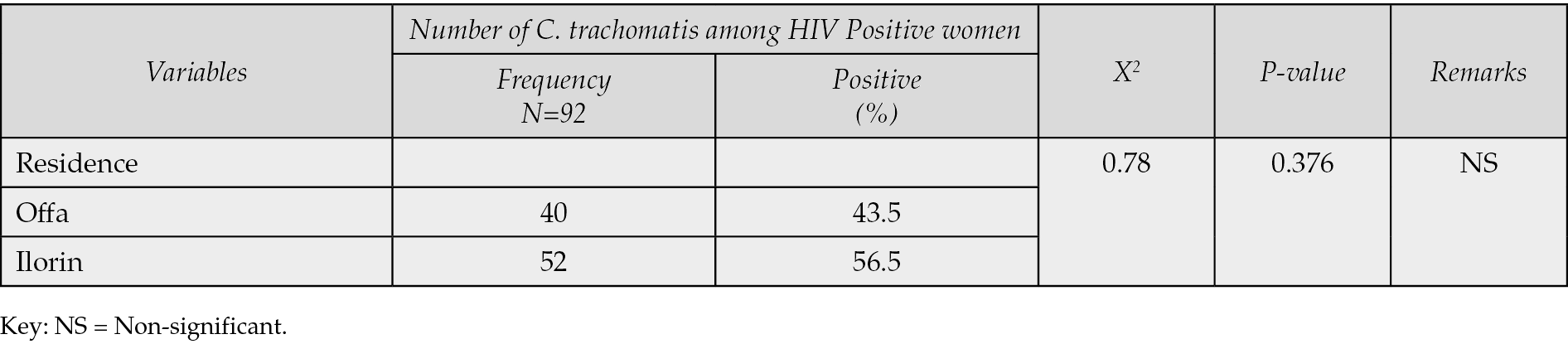

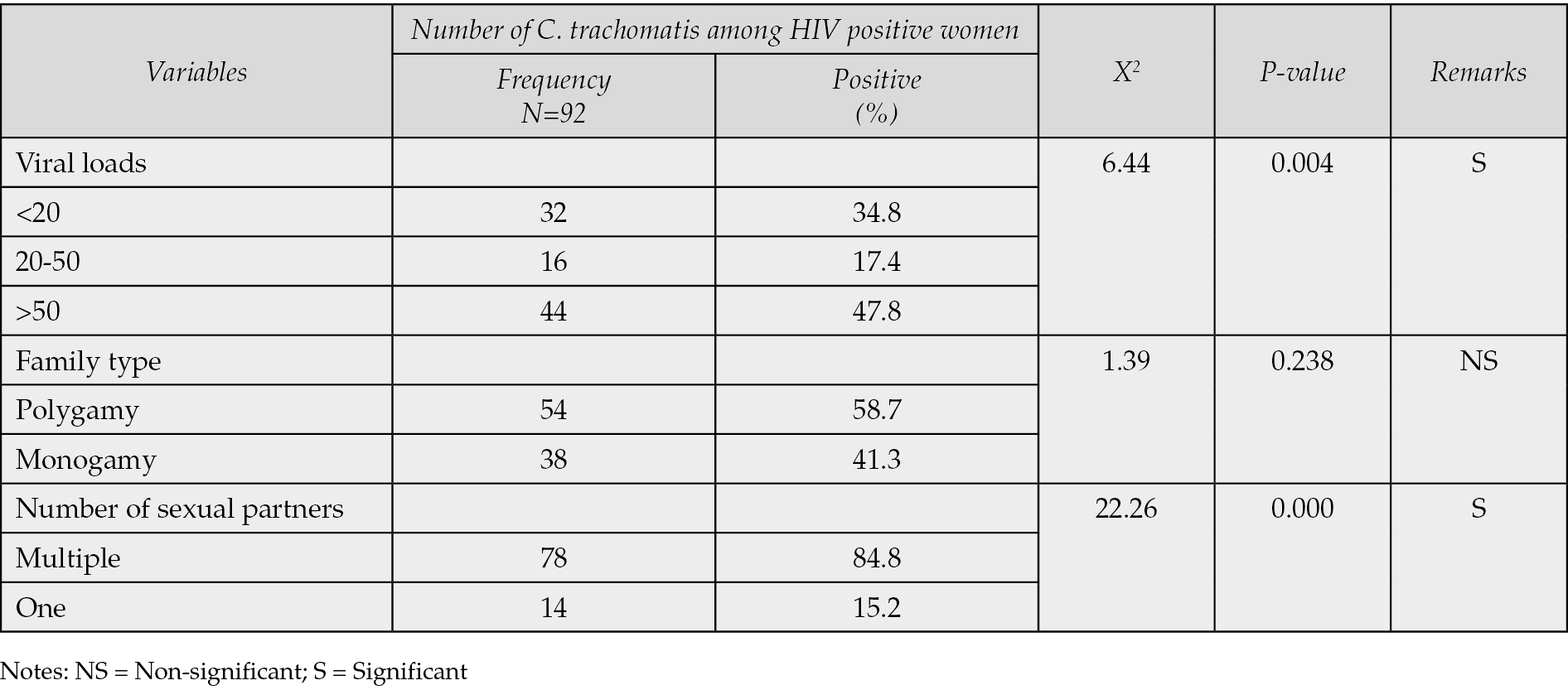

Table 1 demonstrated that only 92 (23.9%) of the 400 HIV-positive women who underwent C. trachomatis seroprevalence testing in Ilorin and Offa, Kwara State, Nigeria, were found to have the infection, whereas 308 (77.0%) were negative. According to Table 2, the age groups with the highest prevalence of C. trachomatis infection were 36-40 years old (52.2%), followed by 40-49 years old (19.6%), 31-35 years old (19.6%), and 21-25 years old (4.4%). The age groups with the lowest frequency were 21-25 years old (2.2%) and 20 years old (2.2%). Age groups did, statistically speaking, correlate significantly (p=0.001) with C. trachomatis seroprevalence among HIV-positive women. The highest prevalence of C. trachomatis was seen among married women who were HIV positive (60.9%), and there was a statistically significant correlation between marital status and seroprevalence of C. trachomatis among HIV positive women (p=0.001) (see Table 3). According to Table 4, the majority of HIV-positive women with C. trachomatis infections (43.5%) had a secondary education, followed by those with higher education (34.8%), elementary education (13.0%), and those with no education (8.7%). Among women who were HIV positive, there was a statistically significant correlation between educational attainment (p=0.001) and the seroprevalence of C. trachomatis. Table 5 revealed that traders (26.1%), hairdressers (23.9%), students (17.4%), civil employees (13.0%), fashion designers (10.9%), and business women (8.7%) made up the bulk of HIV-positive women who also tested positive for C. trachomatis. In the HIV-positive women, there was no statistically significant correlation between occupation (p=0.224) and seroprevalence of C. trachomatis (p>0.05). According to Table 6, the majority of the 56.5% of HIV-positive C. trachomatis-infected women resided in Ilorin, Kwara state, while the remaining 43.5% resided in Offa. Among the HIV-positive women, there was no statistically significant correlation between residency and seroprevalence of C. trachomatis (p=0.376). According to Table 7, HIV-positive women with viral loads >50 copies/mL (47.8%) had the highest prevalence of C. trachomatis, followed by those with viral loads 20 copies/mL (34.8%), and those with viral loads between 20 and 50 copies/mL (40.8%) had the lowest frequency. Among HIV positive women, there was a statistically significant connection between viral loads (p=0.04), seroprevalence of C. trachomatis, and related risk factors. 58.3% of HIV-positive women with C. trachomatis were in polygamous relationships, while 41.7% were in monogamous relationships. In women who were HIV positive, there was no statistically significant relationship between family type (p=0.238) and the seroprevalence of C. trachomatis (p>0.05). A high proportion of C. trachomatis and HIV-positive women had several partners 15.2% and 84.8% only had one sex partner each. The number of sexual partners had a statistically significant relationship (p=0.001) with the seroprevalence of C. trachomatis among HIV positive women (p=0.05).

Table 1 - Seroprevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis among HIV positive women.

Table 2 - Age distribution of Chlamydia trachomatis among HIV positive women in Ilorin/Offa.

Table 3 - Distribution of Chlamydia trachomatis among HIV positive women based on marital status.

Table 4 - Distribution of Chlamydia trachomatis among HIV positive women based on educational level.

Table 5 - Distribution of Chlamydia trachomatis among HIV positive women based on occupation.

Table 6 - Distribution of Chlamydia trachomatis among HIV-positive women based on residence.

Table 7 - Associated risk factors of seroprevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis among HIV positive women.

DISCUSSION

C. trachomatis infection has been acknowledged by WHO as a significant public health issue and has been linked to an acceleration of HIV transmission and acquisition [18-20]. In this study, 400 blood samples were collected and tested for Chlamydia using an Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). Our findings reveal an overall prevalence rate of 23% for C. trachomatis among HIV-positive women in Ilorin and Offa, Kwara State. This is similar to the 29.4% reported in Abuja, Nigeria [21]. However, the prevalence in our study is lower than 45% in Bida, Niger State, a northern part of the country, 54.2% in India, and the prevalence is higher than the findings in Gombe State, Nigeria [22-24]. The different predisposing factors, cultural practices, sexual practices, access to better STI management, and level of public awareness may all play a role in the seroprevalence of C. trachomatis infection in the various populations of HIV-positive women. The likelihood of contracting HIV disease has been connected to chlamydial infection, but immunosuppression brought on by HIV may also cause more severe chlamydial disease conditions, such as pelvic inflammatory diseases (PID) [23, 25]. To reduce the risk of HIV and its deadly clinical effects, it is crucial to diagnose and treat chlamydial infections early.

According to Joyee A, both illnesses have a strong correlation with having several sexual partners [23]. Chlamydia and HIV infections have similar risk factors. HIV infection may be enhanced by C. trachomatis infection due to its invasive intracellular pathogenesis, which can seriously harm the genital epithelial layer. HIV infection might also lead to immunological alterations that favor chlamydial infection [26, 27]. The prevalence of C. trachomatis infection was found to increase with age in this study. The detection of C. trachomatis in HIV positive women was higher in the age group 36-40 years (52.2%) which are sexually active age groups. This is consistent with a previous study in Mpumalanga Province (Nigeria) that found a high prevalence in females aged between 46-50 years old [19]. However, findings from our study contradict those from studies carried out by Rassjo et al. (2006) and Ogedengbe et al. (2013), who declared that the younger age group was associated with active sexual practice and also associated with higher rates of chlamydial infection [22, 28]. Age was found to be significantly associated with the prevalence of C. trachomatis infection among HIV women in Offa and Ilorin. The high prevalence obtained among the age group 36-40 years in this study could be due to the environment in which the study was conducted. Adult women in Ilorin have been known to have multiple sexual partners and might have contracted the infection during sexual activities without using protection.

The prevalence of infection with C. trachomatis among HIV positive women was correlated with marital status. This is in line with a study conducted in Jos, Nigeria, among women who attended gynecologic clinics, which discovered a greater frequency of chlamydia in married women (38.41%) compared to single women (17.07%) and those who had recently undergone divorce (0.61%) [29]. This condition contrasts with that observed by Kolvstad and his colleagues, who found that unmarried women (6.6%) had a greater frequency of C. trachomatis than married women (0%) [30]. These variations could result from various population dynamics in various geographic areas as well as the type of study population chosen. Another study found that having other STIs, living alone or with people other than partners or family, having unprotected vaginal intercourse (UVI), and being younger all appeared to increase the chance of C. trachomatis infection [31].

The seroprevalence of C. trachomatis was substantially correlated with the educational status of women living with HIV, comparable to this study. In 2010, Beydoun and colleagues found that the frequency was higher among those who had only completed high school (4.8%) compared to those who had gone on to post-secondary education (0.8%), and the difference was significant (P=0.004) [32]. It has, however, been shown from this study that the level of education as a socioeconomic factor has an effect on the study population. The high sexual activity among these groups may be the cause of the high prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis infection among women with tertiary and secondary school education. The majority of the seropositive women had some education, so it stands to reason that they would gain from initiatives to raise knowledge of the condition and the use of preventative measures [33].

The prevalence of chlamydial infection was high in HIV women who were traders (26.1%) and there was no significant association of chlamydial infection with the participants’ occupation. This is similar to the high prevalence of C. trachomatis among HIV women who were self-employed and civil servants [19]. The reason for the high prevalence among women who are traders could also be due to a carefree lifestyle, ignorance, and the fact that some of them are promiscuous.

The number of partners among HIV-positive women was substantially correlated with the seroprevalence of C. trachomatis. C. trachomatis was extremely prevalent in those who had several partners. In this region of Nigeria, polygamy is also practiced. According to research, having fewer sex partners lowers your risk of contracting Chlamydia and other STIs [20].

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, prevalence of C. trachomatis was 23.0%. Age and C. trachomatis seroprevalence were related, particularly in HAART clinic attendees between the ages of 30 and 50. Marital status and degree of education were noted to be risk factors for C. trachomatis infection. The finding of anti-C. trachomatis in the sera of HIV-positive women in Ilorin and Offa supports the idea of routine testing for anti-C. trachomatis antibodies and anti-Chlamydia agents among women visiting STD clinics and HIV-positive women.

Limitations

There is no control group of HIV-negative women in the study for comparison. A control group would have made it possible to better comprehend the relationship between C. trachomatis infection and HIV positivity.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all our participants who consented to participate in this study.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Ethical approval

Clearance and approval were collected from the Ministry of Health, Ilorin, and Kwara State with the reference number MOH/KS/EU/777/558,

Competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

All the datasets generated for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

All authors conceived and designed the research, reviewed, analyzed, performed the research and wrote the paper. All authors have read and approved the final draft.

REFERENCES

[1] Klasinc R, Battin C, Paster W. TLR4/CD14/MD2 Revealed as the Limited Toll-like Receptor Complex for Chlamydia trachomatis-Induced NF-κB Signaling. Microorganisms. 2022; 10(12): 2489. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10122489.

[2] Workowski KA, Bachmann LH. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Sexually Transmitted Diseases Infection Guidelines. Clin Infect Dis., 2022; 74 (suppl 2): S89-S94, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab1055.

[3] Zhang Z, Zong X, Bai H, Fan L, Li T, Liu Z. Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium and Chlamydia trachomatis in Chinese female with lower reproductive tract infection: a multicenter epidemiological survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2023; 23(1): 2. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07975-2.

[4] Juliana NCA, Deb S, Ouburg S, et al. The Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis and three other non-viral sexually transmitted infections among pregnant women in Pemba Island Tanzania. Pathogens. 2020; 9(8): 625. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9080625.

[5] Malhotra M, Sood S, Mukherjee A, Muralidhar S, Bala M. Genital Chlamydia trachomatis: an update. Indian J Med Res. 2013; 138(3): 303-316. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24135174.

[6] Malik A, Jain S, Rizvi M, Shukla I, Hakim S. Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women with secondary infertility. Fertil Steril. 2009; 91(1): 91-95. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.070.

[7] O’Connell Catherine M., Ferone Morgan E. Chlamydia trachomatis Genital Infections. Microbial Cell. 2016; 3(9): 390-403. doi: 10.15698/mic2016.09.525.

[8] Paul VK, Singh M, Gupta U, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis infection among pregnant women: prevalence and prenatal importance. Natl Med J India. 1999; 12(1): 11-14. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10326323.

[9] Rashidi BH, Chamani-Tabriz L, Haghollahi F, et al. Effects of Chlamydia trachomatis infection on fertility; a case-control study. J Reprod Infertil [Internet]. 2013 Apr; 14(2): 67-72. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23926567.

[10] Deese J, Pradhan S, Goetz H, Morrison C. Contraceptive use and the risk of sexually transmitted infection: systematic review and current perspectives. Open Access J Contracept. 2018; 9: 91-112. doi: 10.2147/OAJC.S135439.

[11] National Research Council (US) Committee on Population. Contraception and Reproduction: Health Consequences for Women and Children in the Developing World. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1989. PMID: 25144060.

[12] Mtshali A, Ngcapu S, Mindel A, Garrett N, Liebenberg L. HIV susceptibility in women: The roles of genital inflammation, sexually transmitted infections and the genital microbiome. J Reprod Immunol. 2021; 145: 103291. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2021.103291.

[13] Grygiel-Górniak B, Folga BA. Chlamydia trachomatis - An emerging old entity? Microorganisms. 2023; 11(5): 1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11051283.

[14] Govindaraj S, Babu H, Kannanganat S, Vaccari M, Petrovas C, Velu V. Editorial: CD4+ T cells in HIV: a friend or a foe? Front Immunol. 2023; 14: 1203531. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1203531.

[15] Bhattar S, Bhalla P, Chadha S, Tripathi R, Kaur R, Sardana K. Chlamydia trachomatis infection in HIV-infected women: need for screening by a sensitive and specific test. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 2013: 960769. doi: 10.1155/2013/960769.

[16] Newmyer L, Evans M, Graif C. Socially connected neighborhoods and the spread of sexually transmitted infections. Demography. 2022; 59(4): 1299-1323. doi: 10.1215/00703370-10054898.

[17] Bébéar C, de Barbeyrac B. Genital Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009; 15(1): 4-10. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1198743X14605978 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02647.x.

[18] Adegbesan-Omilabu M, Okunade KS, Oluwole AA, Gbadegesin A, Olimabu SA. Chlamydia trachomatis among women with normal and abnormal cervical smears in Lagos, Nigeria.. 501-506. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 3(3): 501-506. Doi: 10.5455/2320-1770.ijrcog20140905.

[19] Mafokwane, T.M., Samie, A. Prevalence of chlamydia among HIV positive and HIV negative patients in the Vhembe District as detected by real time PCR from urine samples. BMC Res Notes, 2016; 9: 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-1887-8.

[20] Vidot DC, Messiah SE, Prado G, Hlaing WM. Relationship between current substance use and unhealthy weight loss practices among adolescents. Matern Child Health J. 2016; 20(4): 870-877. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1875-y.

[21] Izebe KS, Yakubu N, M, Ezeunala EM, et al. Detection of anti-Chlamydia trachomatis Antibodies in Patients with Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome in Abuja, Nigeria. Malaysian J Microbiol. 2008; 4: 44-48. 10.21161/mjm.02108.

[22] Ogedengbe S, Agbah MI, Omosigho OP, et al. Seroprevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis among HIV positive women in Bida, North Central Nigeria. (2020). Inter J Epidemiol Infect. 10.12966/ijei.07.01.2013.

[23] Joyee AG, Thyagarajan SP, Reddy EV, Venkatesan C, Ganapathy M. Genital chlamydial infection in STD patients: its relation to HIV infection. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2005; 23(1): 37-40. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.13871.

[24] Charanchi S, Tahir F. Screenings for Chlamydia trachomatis Antigen among HIV and non-HIV patients with symptoms of urogenital tract diseases at The Federal Medical Centre Gombe, Nigeria. Intern J Infect Dis. 2012; 10(1): 6-11. https://ispub.com/IJID/10/1/14255.

[25] Thomas K, Simms I. Chlamydia trachomatis in subfertile women undergoing uterine instrumentation. How we can help in the avoidance of iatrogenic pelvic inflammatory disease? Hum Reprod. 2002; 17(6): 1431-1432. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.6.1431.

[26] Debattista J, Martin P, Jamieson J, et al. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in an Australian high school student population. Sex Transm Infect. 2002; 78(3): 194-1947. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.3.194.

[27] Wodarz D, Hamer DH. Infection dynamics in HIV-specific CD4 T cells: does a CD4 T cell boost benefit the host or the virus? Math Biosci. 2007; 209(1): 14-29. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2007.01.007.

[28] Råssjö EB, Kambugu F, Tumwesigye MN, Tenywa T, Darj E. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among adolescents in Kampala, Uganda, and theoretical models for improving syndromic management. J Adolesc Health. 2006; 38(3): 213-221. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.10.011.

[29] Mawak JD, Dashe N, Agabi YA, Panshak BW. Prevalence of genital chlamydia trachomatis infection among gynaecologic clinic attendees in Jos, Nigeria. Shiraz E Med J. 2011; 12(2): 100-110. https://brieflands.com/articles/semj-78511.

[30] Kløvstad, H., Grjibovski, A. & Aavitsland, P. Population based study of genital Chlamydia trachomatis prevalence and associated factors in Norway: A cross sectional study. BMC Infect 6Dis. 2012; 12, 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-12-150.

[31] Tang W, Pan J, Jiang N, et al. Correlates of chlamydia and gonorrhea infection among female sex workers: the untold story of Jiangsu, China. PLoS One. 2014 ;9(1): e85985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085985.

[32] Beydoun HA, Dail J, Tamim H, Ugwu B, Beydoun MA. Gender and age disparities in the prevalence of Chlamydia infection among sexually active adults in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010; 19(12): 2183-2190. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.1975.

[33] van Valkengoed IG, Morré SA, van den Brule AJ, Meijer CJ, Bouter LM, Boeke AJ. Overestimation of complication rates in evaluations of Chlamydia trachomatis screening programmes - implications for cost-effectiveness analyses. Int J Epidemiol. 2004; 33(2): 416-425. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh029.